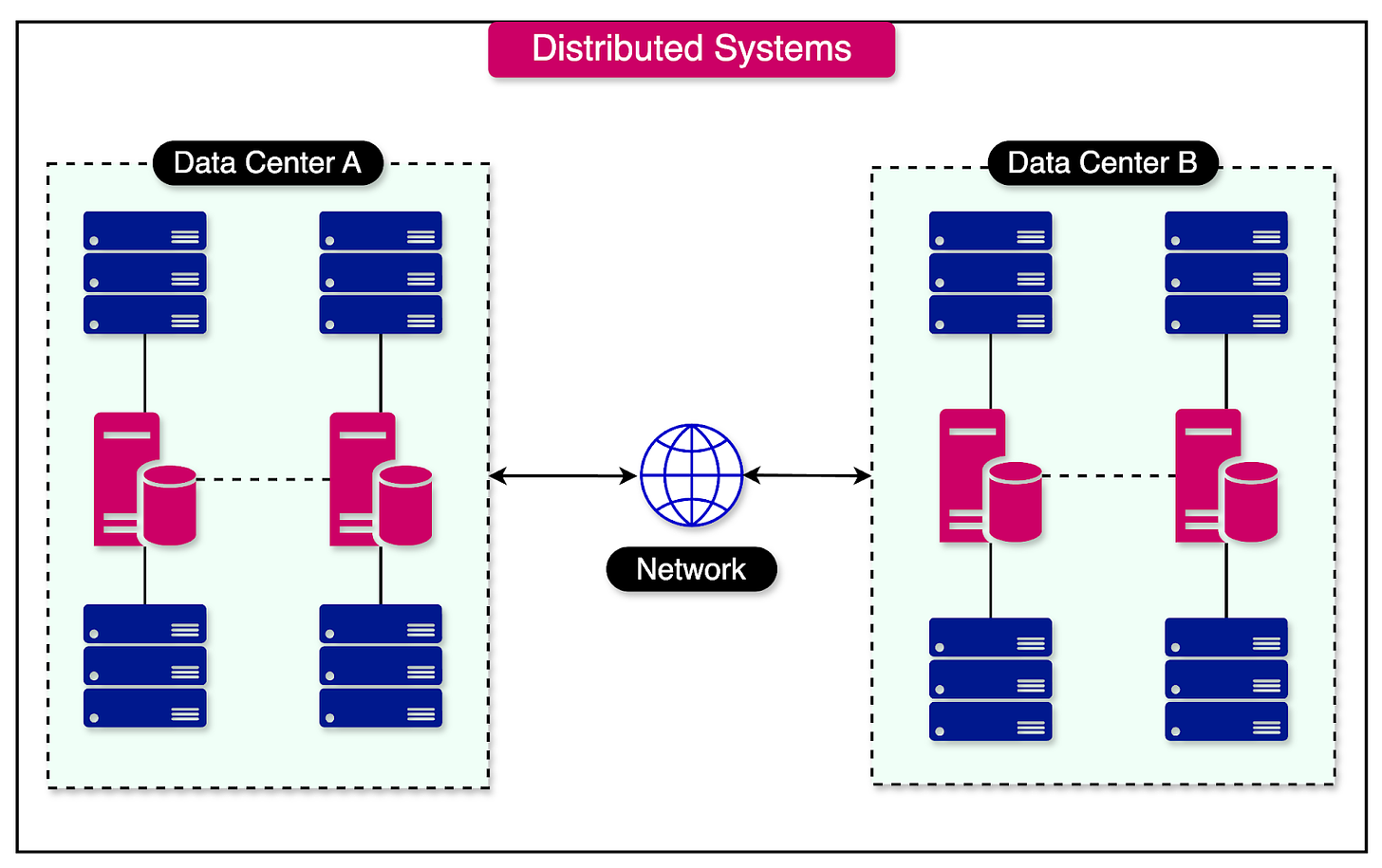

A distributed system is a collection of computers, also known as nodes, that collaborate to perform a specific task or provide a service.

These nodes are physically separate and communicate with each other by passing messages over a network. Distributed systems can span geographical boundaries, enabling them to utilize resources from different locations.

Distributed systems have several characteristics that distinguish them from traditional centralized systems:

The computers in a distributed system are physically separate and connected via a network. They do not share a memory or a common clock.

From an external perspective, a distributed system appears as a single, unified entity to the end user.

Distributed systems offer the flexibility to add or remove computers from the system.

The nodes in a distributed system need to coordinate and agree with each other to perform actions consistently.

Nodes in a distributed system can fail independently, and messages can be lost or delayed over the network.

Distributed systems are ubiquitous in our daily lives. Examples include large web applications like Google Search, online banking systems, multiplayer games, etc. These systems leverage the power of multiple computers working together to provide a seamless and responsive user experience.

In this post, we’ll explore the benefits and challenges of distributed systems. We will also discuss common approaches and techniques used to address these challenges and ensure the reliable operation of distributed systems.

The term “distributed systems” can sometimes confuse developers.

A couple of common confusions are around decentralized systems and parallel systems.

Let’s understand the meaning of these terms in the context of a distributed system and how they are similar or different.

Terms like “Decentralized Systems” and “Distributed Systems” are often used interchangeably, but they have a key difference.

While both types of systems involve multiple components working together, the decision-making process sets them apart.

In a decentralized system, which is also a type of distributed system, no single component has complete control over the decision-making process. Instead, each component owns a part of the decision but does not possess the complete information required to make an independent decision.

Another term that is closely associated with distributed systems is parallel systems.

Both distributed and parallel systems aim to scale up computational capabilities, but they achieve this goal using different means.

In parallel computing, multiple processors within a single machine perform multiple tasks simultaneously. These processors often have access to shared memory, allowing them to exchange data and efficiently coordinate their activities.

On the other hand, distributed systems are made up of multiple autonomous machines that do not share memory. These machines communicate and coordinate their actions by passing messages over a network. Each machine operates independently, contributing to the overall computation by performing its assigned tasks.

While designing and building distributed systems can be more complex than traditional centralized systems, their benefits make the effort worthwhile.

Let's explore some of the key advantages of distributed systems:

Scalability: Vertical scaling, which involves increasing the hardware resources of a single machine, is often limited by physical constraints. For example, there is a limit to the number of processor cores that can be added to a single machine. In contrast, distributed systems enable horizontal scaling, where additional commodity machines can be added to the system. This allows scaling a system by adding relatively inexpensive hardware.

Reliability: Distributed systems are more resilient to failures compared to centralized systems. Since data is replicated across multiple nodes, the failure of a single node or a subset of nodes does not necessarily bring down the entire system. The remaining nodes can continue to function, albeit at a reduced capacity, ensuring the overall system remains operational.

Performance: Distributed computing often involves breaking down a complex workload into smaller, manageable parts that can be processed simultaneously on multiple machines. This parallel processing capability improves the performance of computationally intensive tasks, such as matrix multiplications or large-scale data processing.

Distributed systems also pose multiple challenges when it comes to operating them.

Knowing about these challenges and the techniques to overcome them is the key to taking advantage of distributed systems.

Let’s explore the main challenges of distributed systems and the techniques to handle them.

In a distributed system, nodes need to communicate and coordinate with each other over a network to function as a cohesive unit.

However, this communication is challenging due to the unreliable nature of the underlying network infrastructure.

The Internet Protocol (IP), which is responsible for delivering packets between nodes, only provides a "best effort" service. This means that the network does not guarantee the reliable delivery of packets.

Several issues can arise during packet transmission:

Packet Loss: Packets can be lost or dropped along the way due to network congestion, hardware failures, or other factors.

Packet Duplication: In some cases, packets can be duplicated, resulting in multiple copies of the same packet being delivered to the destination node.

Packet Corruption: Packets can get corrupted during transmission. Corrupted packets may contain invalid or incorrect data, leading to communication errors.

Out-of-Order Delivery: Packets can arrive at the destination node in a different order than they were sent.

Building reliable communication on top of this unreliable foundation is a significant challenge.

Some key techniques used by distributed systems to handle these issues are as follows:

The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) is a fundamental protocol that provides a robust mechanism for ensuring the reliable, in-order delivery of a byte stream between processes, making it a cornerstone of reliable data transmission in distributed systems.

It employs several key mechanisms to overcome the inherent unreliability of the network:

TCP splits the byte stream into smaller, sequenced packets called segments.

It requires the receiver to send an acknowledgment (ACK) to the sender upon receiving the packet.

TCP uses checksums to verify the integrity of the transmitted data.

TCP implements flow control to prevent the sender from overwhelming the receiver with data.

Lastly, TCP employs congestion control mechanisms to adapt to the available network bandwidth.

The diagram below shows the TCP 3-way handshake process that establishes the connection between a client and the server.

While TCP ensures reliable communication over an unreliable network, it does not address the security aspects of data transmission. This is where the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol comes into play.

TLS is a cryptographic protocol that adds encryption, authentication, and integrity to the communication channel established by TCP.

TLS uses several mechanisms to secure the communication between the nodes:

TLS uses a combination of asymmetric and symmetric encryption to protect the confidentiality of data.

TLS relies on digital certificates to authenticate the identity of the communicating parties.

To ensure the integrity of the transmitted data, TLS includes checksums or message authentication codes with each message.

In a distributed system, nodes need a mechanism to discover and communicate with each other. This is where the Domain Name System (DNS) comes into play, solving the service discovery problem.

DNS acts as the "phone book of the internet," providing a mapping between human-readable domain names and their corresponding IP addresses. It allows nodes to locate and connect to each other using easily memorable names instead of complex numerical IP addresses.

The diagram below shows the service discovery process between a consumer and a provider.

Under the hood, DNS is implemented as a distributed, hierarchical key-value store. It consists of a network of servers that work together to resolve domain names to IP addresses.

The hierarchical structure of DNS enables efficient and scalable name resolution across the internet.

Coordination between nodes is a critical challenge while building distributed systems.

Some key coordination-related problems are as follows:

Potential for Failures: In a distributed system, individual components, such as servers or network devices, can fail at any time. These failures can disrupt the flow of information and lead to inconsistencies if not handled properly.

Unreliable Networks: As seen earlier, distributed systems communicate over networks that are prone to delays, packet loss, and other issues. This makes coordinating the exchange of information reliably a big challenge.

Lack of Global Clock: Since distributed systems lack a global clock, it is difficult to establish a consistent notion of time across all components.

Let’s look at some key techniques used to solve the coordination-related challenges of distributed systems:

In a distributed environment, it is impossible to definitively distinguish between a failed process and a process that is simply very slow in responding.

The reason for this ambiguity lies in the fact that network delays, packet loss, or temporary network partitions can cause a process to appear unresponsive, even though it may still be functioning correctly.

To address this challenge, distributed systems employ failure detectors.

Failure detectors are components that monitor the status of processes and determine their availability. However, failure detectors must make a tradeoff between detection time and the rate of false positives.

If a failure detector is configured to detect failures quickly, it may incorrectly classify slow processes as failed, resulting in a higher false positive rate. On the other hand, if the failure detector is configured to be more conservative and allow more time for processes to respond, it may take longer to detect actual failures, leading to a slower detection time.

Agreeing on the timing and order of events is a big coordination challenge in distributed systems.

One of the primary reasons for this challenge is the imperfect nature of physical clocks in distributed systems. Each node in the system has its physical clock, which is typically based on a quartz crystal oscillator. These physical clocks are subject to drift and can gradually diverge from each other over time. Even small variations in clock frequencies can lead to significant discrepancies in the perceived time across nodes.

Moreover, achieving a total order of events in a distributed system requires coordination among the nodes. In a total order, all nodes agree on the exact sequence of events, regardless of the causal relationships between them.

To address these challenges, distributed systems often rely on logical clocks and vector clocks to capture the causal ordering of events.

Logical clocks, such as Lamport timestamps, assign monotonically increasing timestamps to events based on the local clock of each node. These timestamps establish a partial order of events, capturing the "happens-before" relationship between them.

Vector clocks, on the other hand, provide a more comprehensive representation of the causal relationships between events. Each node maintains a vector of logical timestamps, with one entry per node in the system. When an event occurs, the node increments its timestamp and includes the maximum timestamp of all other nodes it has communicated with. By comparing vector clock values, nodes can determine the causal relationships between events and detect potential conflicts or inconsistencies.

The diagram below shows the difference between logical Lamport clocks and vector clocks.

In distributed systems, many coordination tasks, such as holding a lock or committing a transaction, require the presence of a single "leader" process.

The leader is responsible for managing and coordinating the execution of these tasks.

Raft is a widely adopted consensus algorithm that addresses the challenge of leader election in a distributed environment. It provides a mechanism for electing a leader among a group of processes, ensuring that there is at most one leader per term.

The Raft algorithm operates in terms of "terms," which represent a logical clock or a timeframe in which a leader is elected and serves their role. Each term is assigned a unique, monotonically increasing number.

One of the key principles of Raft is that a candidate process can only become the leader if its log is up-to-date. In other words, the candidate must have the most recent and complete set of log entries compared to other processes in the system.

The diagram below shows a mapping of state changes (follower, candidate, and leader) that a node can go through as part of the Raft consensus algorithm.

Keeping replicated data in sync across multiple nodes is a fundamental coordination challenge in distributed systems.

Replication is essential for ensuring data availability and fault tolerance, but it introduces the complexity of maintaining consistency among the replicas.

The CAP theorem states that in a distributed system, it is impossible to provide consistency, availability, and partition tolerance simultaneously.

According to the theorem, a distributed system can only provide two of the three guarantees at any given time. In the presence of network partitions, there is a trade-off between consistency and availability. Systems must choose to either maintain strong consistency at the cost of reduced availability or prioritize availability while accepting weaker consistency guarantees.

Also, distributed systems support multiple consistency models that define the guarantees for read and write operations on replicated data.

Linearizability: Linearizability is the strongest consistency model. It ensures that each operation appears to take effect instantaneously at some point between its invocation and completion.

Sequential Consistency: Sequential consistency is weaker than linearizability. It guarantees that the result of any execution is the same as if the operations of all processes were executed in some sequential order.

Causal consistency: It ensures that causally related operations (e.g., a write that influences a subsequent read) are seen in the same order by all processes.

Eventual Consistency: This is the weakest consistency model. It guarantees that if no new updates are made to a data item, eventually all reads for that item will return the last updated value.

As discussed earlier, scalability is one of the key benefits of adopting distributed systems. A scalable system can increase its capacity to handle more load by adding resources.

However, choosing the right scalability patterns is also important.

Let’s look at a few key patterns for scaling a distributed system.

An example of functional decomposition is breaking down a monolithic application into smaller, independently deployable services. Each service has its well-defined responsibility and communicates with other services through APIs.

An API Gateway acts as a single entry point for external clients to interact with microservices. It handles request routing and composition by providing a unified interface to the clients.

Another functional decomposition approach is a pattern like CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation).

CQRS is a pattern that separates the read and write paths of an application.

This optimizes performance by allowing read and write operations to scale independently. CQRS is often used in conjunction with microservices to enable efficient data retrieval and modification.

The functional decomposition approach also relies on asynchronous messaging as a communication pattern.

It helps decouple services, enabling resilience and scalability. Services communicate through message queues or publish-subscribe systems, enabling them to process requests at their own pace and prevent overload.

Partitioning is a fundamental technique used in distributed systems to split a large dataset across multiple nodes when it becomes too large to be stored and processed on a single node.

By distributing the data, partitioning enables horizontal scalability and allows the system to handle increasing data volumes.

The diagram below shows the concept of data partitioning where the book table is partitioned based on the category field.

There are several techniques used for partitioning data:

Range Partitioning: It involves splitting the data based on a specific key range. Each partition is responsible for storing a contiguous range of keys. While this approach enables faster range scans, it can also lead to potential hot spots if certain key ranges receive disproportionate traffic or data.

Hash Partitioning: Hash partitioning distributes data evenly across partitions using a hash function. While hash partitioning ensures a more uniform data distribution, it loses the natural ordering of keys, making range scans less efficient.

Rebalancing: Rebalancing is the process of moving partitions between nodes as the cluster size changes to maintain a balanced distribution of data.

Consistent Hashing: Consistent hashing is a partitioning technique that minimizes data movement when nodes are added or removed from the cluster.

Duplication is an important technique used in distributed systems to scale capacity and increase availability by introducing redundancy of components.

By duplicating servers, data, and other resources, systems can handle higher loads and provide resilience against failures.

Some key techniques that enable duplication are as follows:

Load Balancing: Load balancing is the process of distributing incoming requests across a pool of servers to ensure optimal resource utilization. Load balancers use various algorithms to determine which server should handle a particular request. Also, we can implement load balancing at different layers of the network stack such as:

DNS-based load balancing to distribute requests at the DNS level.

Layer 4 load balancing to distribute requests based on transport layer information such as IP addresses and port numbers.

Layer 7 load balancing to distribute requests based on application-level information, such as HTTP headers, URLs, or session data.

Server-Side Discovery: To support dynamic scaling, distributed systems employ server-side discovery. It enables servers to dynamically register themselves with a central registry or discovery service. Health checks are performed to monitor the status of servers and detect failures.

Data Replication: Replication involves creating multiple copies of data across different nodes in a distributed system. There are different replication styles, such as:

Single-leader replication: One node acts as the leader, handling write operations and critical reads, while other nodes serve as followers.

Multi-leader replication: Multiple nodes can accept write operations, and changes are propagated asynchronously between the leaders.

Leaderless replication: All nodes accept write operations, and consistency is maintained through techniques like quorum consensus.

The diagram below shows how a load balancer helps distribute traffic between multiple service instances.

Resiliency is the ability of a system to continue functioning correctly in the face of failures.

As distributed systems scale in size and complexity, failures become not just possible but inevitable. Some of the most common causes of failures are as follows:

Hardware failures of servers, storage, and the network.

Software bugs and memory leaks.

Human errors in configuration and deployment.

Cascading failures where a fault in one component triggers faults in others.

Unexpected load spikes overwhelm the capacity.

There are two main categories to manage a component’s resiliency within a distributed system.

When services interact through synchronous request/response communication, it’s important to stop faults from propagating from one component or service to another.

Key techniques to make this possible are as follows:

Timeouts: They are used to prevent a service from waiting indefinitely for a response from another service. By setting a reasonable timeout value, the calling service can avoid being blocked for an extended period if the called service is unresponsive. When the timeout occurs, the calling service can take appropriate action, such as returning an error or falling back to a default behavior.

Retries with Exponential Backoff: Retries are a common pattern to handle transient failures, such as temporary network issues. When a request fails, the calling service can retry the request after a certain delay. However, to avoid overwhelming the called service with a flood of retries, exponential backoff is employed. The delay between each retry is increased exponentially, giving the called service time to recover.

Circuit Breakers: Circuit breakers help prevent cascading failures when a service is unhealthy or unresponsive. The circuit breaker acts as an intermediary between the calling service and the called service. It monitors the success and failure of requests. If the failure rate crosses a certain threshold, the circuit breaker trips and rejects subsequent requests. This fail-fast approach prevents the calling service from waiting on a failing service.

The diagram below shows the circuit breaker pattern and the three states of the circuit breaker.

Resiliency techniques are relevant even at the level of the service owner. There are multiple strategies to protect a service from being overwhelmed by incoming requests.

Let’s look at the most important ones:

Load Shedding: It involves rejecting a portion of the incoming requests when the service is overloaded or experiencing high demand. By selectively dropping requests, the service maintains its responsiveness and prevents a complete breakdown.

Rate Limiting and Throttling: These two techniques are used to ensure fair usage of a service by its clients. Rate limiting sets the maximum number of requests that a client can make within a specific time window. Throttling, on the other hand, involves slowing down the processing of requests when a client exceeds a certain threshold.

Bulkheads: Bulkheads are a resiliency pattern inspired by the compartmentalization technique used in ship design. In the context of services, bulkheads involve isolating different parts of the system to prevent failures in one part from spreading to others.

Health Checks with Load Balancer Integration: Health checks are periodic assessments of a service instance’s health and availability. By regularly monitoring the health of service instances, a load balancer can detect and route traffic away from unhealthy or unresponsive instances.

In this article, we’ve explored distributed systems in great detail. We’ve understood the meaning of distributed systems, their benefits, and the challenges they create for developers.

Let’s summarize the learnings in brief:

A distributed system is a collection of computers, also known as nodes, that collaborate to perform a specific task or provide a service.

In a distributed system, each machine operates independently, contributing to the overall computation by performing its assigned tasks.

The key benefits of distributed systems include scalability, reliability, and performance.

Distributed systems also pose several challenges around communication, coordination, scalability, and resiliency. However, multiple techniques can be used to solve these challenges.

Communication is challenging in distributed systems due to the unreliable nature of the underlying network infrastructure. This is solved by using protocols such as TCP for reliable communication, TLS for secure communication, and DNS for service discovery.

Since distributed systems consist of multiple components, coordinating between them is a big challenge. Techniques such as failure detection, event ordering and timing, leader election, and consistency levels help improve coordination within a distributed system.

Scalability is a major benefit of the distributed systems. However, it is important to choose the right scaling pattern. Some common patterns include functional decomposition into microservices, data partitioning, and duplication of resources with replication and load balancing.

As distributed systems scale, failures become unavoidable and resiliency becomes a significant challenge. Several techniques can be used for downstream resiliency (such as timeouts, retries, and circuit breakers) and upstream resiliency (load shedding, rate limiting, and bulkhead pattern).