As an application grows in popularity, it attracts more active users and incorporates additional features. This growth leads to a daily increase in data generation, which is a positive indicator from a business perspective.

However, it can also pose challenges to the application's architecture, particularly in terms of database scalability.

The database is a critical component of any application, but it is also one of the most difficult components to scale horizontally. When an application receives increased traffic and data volume, the database can become a performance bottleneck, impacting the user experience.

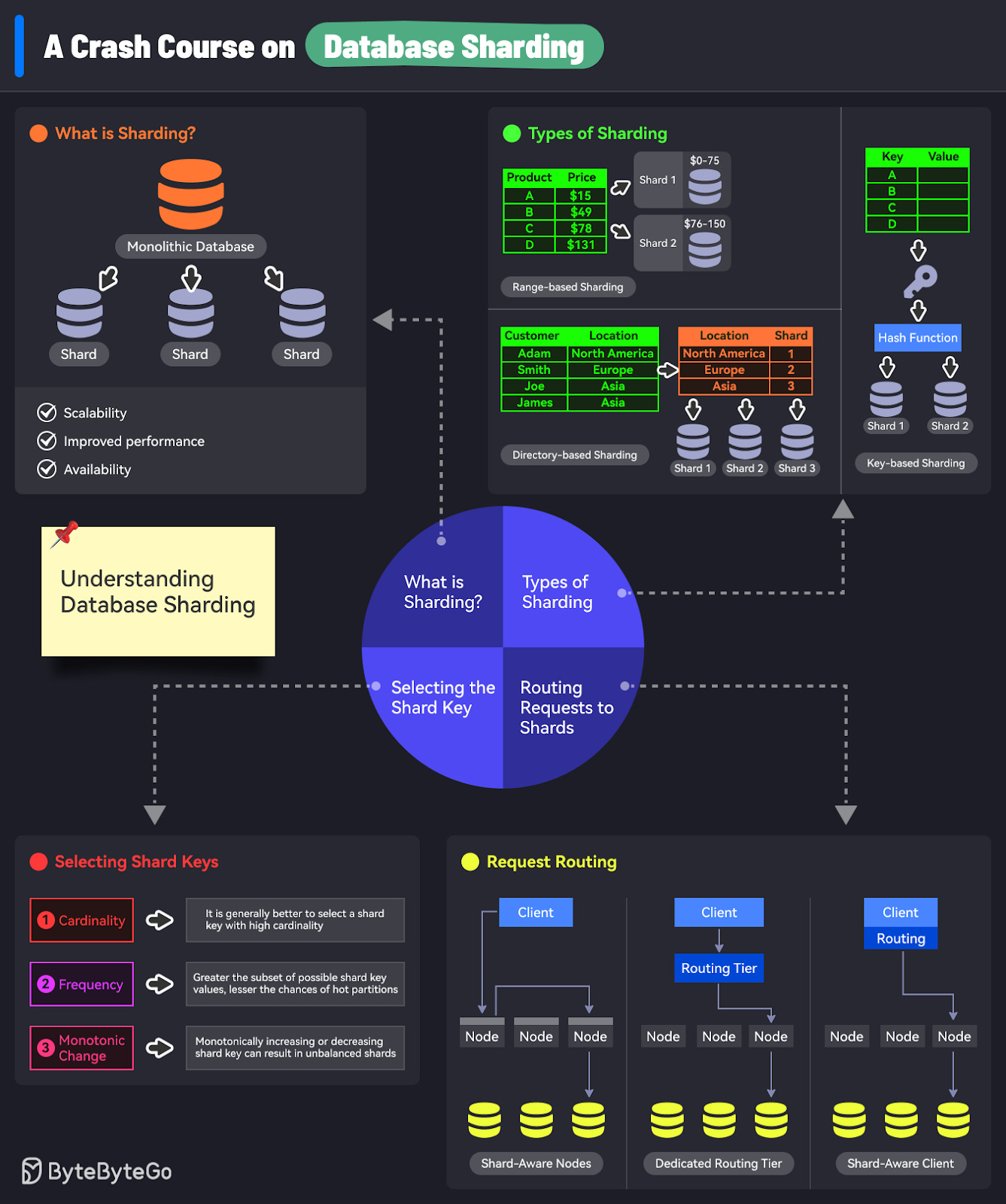

Sharding is a technique that addresses the challenges of horizontal database scaling. It involves partitioning the database into smaller, more manageable units called shards.

In this post, we’ll cover the fundamentals of database sharding, exploring its various approaches, technical considerations, and real-world case studies showcasing how companies have implemented sharding to scale their databases.

Sharding is an architectural pattern that addresses the challenges of managing and querying large datasets in databases. It involves splitting a large database into smaller, more manageable parts called shards.

Sharing builds upon the concept of horizontal partitioning, which involves dividing a table's rows into multiple tables based on a partition key. These tables are known as partitions. Distributing the data across partitions reduces the effort required to query and manipulate the data.

The diagram below illustrates an example of horizontal partitioning.

Database sharding takes horizontal partitioning to the next level. While partitioning stores all the data groups within the same computer, sharding distributes them across different computers or nodes. This approach enables better scalability and performance by leveraging the resources of multiple machines.

It's worth noting that the terminology used for sharding varies across different databases.

In MongoDB, a partition is referred to as a shard.

Couchbase uses the term vBucket to represent a shard.

Cassandra refers to a shard as a vNode.

Despite the differences in terminology, the underlying concept remains the same: dividing the data into smaller, manageable units to improve query performance and scalability.

Database sharding offers several key benefits:

Scalability: The primary motivation behind sharding is to achieve scalability. By distributing a large dataset across multiple shards, the query load can be spread across multiple nodes. For queries that operate on a single shard, each node can independently execute the queries for its assigned data. Moreover, new shards can be added dynamically at runtime without the need to shut down the application for maintenance.

Improved Performance: Retrieving data from a single large database can be time-consuming. The query needs to search through a vast number of rows to locate the required data. In contrast, shards contain a smaller subset of rows compared to the entire database. This reduced search space results in faster data retrieval, as the query has fewer rows to process.

Availability: In a monolithic database architecture, if the node hosting the database fails, the dependent application also experiences downtime. Database sharding mitigates this risk by distributing the data across multiple nodes. In the event of a node failure, the application can continue to operate using the remaining shards.

Sharding is often used with replication to achieve high availability and fault tolerance in distributed database systems.

Replication involves creating multiple copies of data and storing them on different nodes. In a leader-follower replication model, one node acts as the leader and handles write operations, while follower nodes replicate the leader's data and handle read operations.

By replicating each shard across multiple nodes, the system ensures that data remains accessible even if individual nodes fail. A node can store multiple shards, each of which may be a leader or a follower in a leader-follower replication model.

The diagram below illustrates an arrangement where each shard's leader is assigned to one node, and its followers are distributed across other nodes:

In this setup, a node can simultaneously serve as the leader for some partitions and a follower for others. This distributed architecture allows the system to maintain data availability and resilience in case of node failures or network disruptions.

The primary objective of database sharding is to evenly distribute the data and the query load across multiple nodes.

However, if the data partitioning is not balanced, some shards may end up handling a disproportionately higher amount of data or queries compared to others. This scenario is known as a skewed shard, and it diminishes the benefits of sharding.

In extreme cases, a poorly designed sharding strategy can result in a single shard bearing the entire load while the remaining shards remain idle.

This situation is referred to as a hot spot, where one node becomes overwhelmed with a disproportionately high load.

To mitigate the risks of skewed shards and hot spots, it is crucial to select an appropriate sharding strategy that ensures an even distribution of data and queries across the shards.

Let's understand some commonly used sharding strategies:

Range-based sharding is a technique that splits database rows based on a range of values.

In this approach, each shard is assigned a continuous range of keys, spanning from a minimum to a maximum value. The keys within each shard are maintained in a sorted order to enable efficient range scans.

To illustrate this concept, let's consider a product database that stores product information.

Range-based sharding can be applied to split the database into different shards based on the price range of the products. For instance, one shard can store all products within the price range of $0 to $75, while another shard can contain products within the price range of $76 to $150.

It's important to note that the ranges of keys do not necessarily need to be evenly spaced. In real-world applications, data distribution may not be uniform, and the key ranges can be adjusted accordingly to achieve a balanced data distribution across the shards.

However, range-based sharding has a potential drawback.

Certain access patterns can lead to the formation of hot spots. For example, if a significant portion of the products in the database falls within a specific price range, the shard responsible for storing that range may experience a disproportionately high load, while other shards remain underutilized.

Key-based sharding, also known as hash-based sharding, is a technique that assigns a particular key to a shard using a hash function.

A well-designed hash function plays a crucial role in achieving a balanced distribution of keys. Instead of assigning a range of keys to each shard, hash-based sharding assigns a range of hashes to each shard. Consistent Hashing is one technique that’s often used to implement hash-based sharding.

The diagram below illustrates the basic concept of key or hash-based sharding:

One of the main advantages of hash-based sharding is its ability to distribute keys fairly among the shards. By applying a hash function to the keys, the technique helps mitigate the risk of hot spots.

However, hash-based sharding comes with a trade-off. By using the hash of the key instead of the key itself, we lose the ability to perform efficient range queries. This is because adjacent keys may be scattered across different partitions, and their natural sort order is lost in the process.

It's important to note that while hash-based sharding helps reduce hot spots, it cannot eliminate them. In extreme cases where all reads and writes are concentrated on a single key, all requests may still be routed to the same partition. For example, on a social media website, a celebrity user can post content that generates a large volume of writes to the same key.

Directory-based sharding is an approach that relies on a lookup table to determine the distribution of records across shards.

The lookup table serves as a directory or an address book, mapping the relationship between the data and the specific shard where it resides. This table is stored separately from the shards themselves.

The diagram below illustrates the concept of directory-based sharding, using the "Location" field as the shard key:

One of the main advantages of directory-based sharding is its flexibility compared to other sharding strategies. It allows for greater control over the placement of data across shards, as the mapping between data and shards is explicitly defined in the lookup table.

However, directory-based sharding also has a significant drawback: it heavily relies on the lookup table. Any issues or failures related to the lookup table can impact the overall performance and availability of the database.

Choosing an appropriate shard key is crucial for implementing an effective sharding strategy. Database designers should take into account several key factors when making this decision:

Cardinality refers to the number of possible values that a shard key can have. It determines the maximum number of shards that can be created.

For example, if a boolean data field is chosen as the shard key, the system will be limited to only two shards.

To maximize the benefit of horizontal scaling, it is generally recommended to select a shard key with high cardinality.

The frequency of a shard key represents how often a particular shard key value appears in the dataset.

If a significant portion of the records contains only a subset of the possible shard key values, the shard responsible for storing that subset may become a hotspot.

For instance, if a fitness website’s database uses age as the shard key, most records may end up in the shard containing subscribers between the ages of 30 and 45, leading to an uneven distribution of data.

Monotonic change refers to the shard key value increasing or decreasing over time for a given record.

If a shard key is based on a value that increases or decreases monotonically, it can result in unbalanced shards.

Consider a sharding scheme for a database that stores user comments.

Shard A stores data for users with less than 10 comments.

Shard B stores data for users with 11-20 comments.

Shard C stores data for users with more than 30 comments.

As users continue to add comments over time, they will gradually migrate to Shard C, making it more unbalanced than Shards A and B.

Over time, a database undergoes various changes that necessitate the redistribution of data and workload across the nodes. These changes include:

Increased query throughput requires additional CPU resources.

Growth in dataset size demands more storage capacity.

Failure of a particular machine results in other machines taking over its responsibilities.

All these scenarios share a common theme: the need to move data and requests from one node to another within the cluster. This process is known as shard rebalancing.

Shard rebalancing aims to achieve several key goals:

Fair Load Distribution: After the rebalancing process, the workload should be evenly distributed among the nodes in the cluster.

Minimal Disruption: The database should continue accepting read and write operations during the rebalancing process.

Efficient Data Movement: The amount of data moved between nodes should be kept to a minimum.

Considering these objectives, several approaches can be employed for shard rebalancing, each with its trade-offs and considerations.

In a fixed partition configuration, the number of shards is determined when the database is initially set up and typically remains unchanged thereafter.

For instance, consider a database running on a cluster of 10 nodes. It can be split into 100 shards, with 10 shards assigned to each node. The total number of shards (100 in this case) remains fixed.

If a new node is added to the cluster, the system can rebalance the shards by migrating a few shards from the existing nodes to the new node to maintain a fair distribution.

The diagram below illustrates the concept of fixed partitioning:

It's important to note that in this approach, neither the number of shards nor the assignment of keys to shards changes. Only entire shards are moved between nodes during the rebalancing process.

However, the fixed partition approach presents a challenge in choosing the appropriate number of shards if the total size of the data is highly variable.

Also, deciding the size of a single shard requires some consideration:

If the shards are too large, rebalancing and recovery from node failures can become time-consuming and resource-intensive.

On the other hand, if the shards are too small, there is an increased overhead in maintaining and managing them.

Dynamic sharding is an approach that adjusts the number of shards based on the total volume of data stored in the database.

When the dataset is relatively small, dynamic sharding maintains a low number of shards, minimizing the overhead associated with shard management and maintenance.

As the dataset grows and reaches a significant size, dynamic sharding automatically increases the number of shards to accommodate the expanded data volume. The size of each partition is typically limited to a configurable maximum threshold.

When adding new shards, the system redistributes a portion of the data from existing shards to the newly created ones. This process ensures that the data remains evenly distributed across all shards.

One key advantage of dynamic sharding is its flexibility. It can be applied to both range-based sharding and hash-based sharding strategies.

After sharding the dataset, the most critical consideration is determining how a client knows which node to connect to for an incoming request.

This problem becomes challenging because shards can be rebalanced, and the assignment of shards to nodes can change dynamically.

There are three main approaches to address this challenge:

Shard-Aware Node: In this approach, the clients can contact any node using a round-robin load balancer. If the contacted node owns the shard relevant to the request, it can handle the request directly. Otherwise, it forwards the request to the appropriate shard and routes the response back to the client.

Routing Tier: With this approach, client requests are sent to a dedicated routing tier that determines the node responsible for handling each request. The routing tier forwards the request to the appropriate node and returns the response to the client. The application communicates with the routing tier, not the nodes directly.

Shard-Aware Client: In this approach, clients are aware of the shard distribution across nodes. The client first contacts a configuration server to obtain the current shard-to-node mapping. Using this knowledge, the clients can then directly connect to the appropriate node for each request.

The diagram below shows the three approaches:

Regardless of the approach chosen, there is a common decision to make: how to keep the component making the routing decision updated about the shard-to-node mapping.

Different databases employ different mechanisms to achieve this:

LinkedIn’s Espresso uses Helix for cluster management, which relies on Zookeeper to store the configuration information.

MongoDB utilizes a separate configuration server and a dedicated routing tier.

Cassandra employs a gossip protocol among the nodes to propagate any changes to the mapping across all nodes.

After exploring the concepts of sharding, let's explore how popular databases implement sharding in practice.

We'll use MongoDB, one of the most widely used document databases, as our example. MongoDB's sharding architecture demonstrates how the components we've discussed (shards, routing, and configuration) work together to create a scalable distributed database.

MongoDB's sharding architecture relies on a cluster of interconnected servers, also known as nodes. This cluster, referred to as the sharded cluster, consists of three key components:

Shard

Mongos Router

Config Servers

The diagram below shows the interconnection between these three components:

A shard is a subset of the data in the cluster.

Each shard is implemented as a replica set, which is a cluster of individual MongoDB instances.

By deploying each shard as a replica set, MongoDB enables data replication within the shard. This design choice ensures high availability and fault tolerance.

The Mongos Router is the heart of the cluster. It serves as the central component that orchestrates the interaction between the client application and the shards.

The Mongos Router performs two essential functions:

Query Routing and Load Balancing: The router acts as the single entry point for the client application. It receives incoming queries and routes them to the appropriate shards based on the shard key and the data distribution.

Metadata Caching: The router also maintains a cache of the metadata that maps the data to the corresponding shards. It retrieves this metadata from the config servers and caches it locally for better performance.

The Config Server stores and manages the metadata for the entire cluster.

The metadata stored in the config servers include details such as:

Shard configuration: Information about each shard, including its name, host, and port.

Chunk distribution: Mapping data chunks to specific shards, enabling efficient data retrieval.

Cluster state: Current state and health of the sharded cluster, including the status of individual shards and Mongos instances.

The Mongos instances heavily rely on the config servers to make the correct routing decisions.

This architecture provides several benefits:

Scalability: By distributing data across multiple shards, MongoDB can handle large datasets and high query volumes.

High Availability: Replicating data within each shard ensures data redundancy and fault tolerance.

Load Balancing: The Mongos router distributes queries across the shards, ensuring an even workload distribution.

Let’s examine a couple of real-world case studies of organizations using sharding to scale their databases and the issues they face.

In mid-2020, Notion, a popular productivity and collaboration platform, was facing an existential threat.

The company had relied on a monolithic PostgreSQL database for five years, which had supported its tremendous growth through several orders of magnitude. However, as Notion continued to expand rapidly, the database struggled to keep pace.

Several indicators pointed to the growing strain on the database:

Frequent CPU spikes in the database nodes.

Unsafe migrations.

A high volume of on-call requests.

Moreover, two major issues came to the forefront:

VACUUM Stalling: The PostgreSQL VACUUM process, responsible for cleaning up and reclaiming disk space, began to stall. This meant that the database was not effectively managing its storage, leading to performance degradation.

TXID Wraparound: Notion encountered an existential threat in the form of TXID wraparound. This issue occurs when the transaction ID counter in PostgreSQL reaches its maximum value and wraps around to zero. If not addressed, it can lead to data corruption and failure.

Faced with these challenges, Notion’s engineering team decided to implement database sharding.

While they explored vertical scaling as an option, it proved to be cost-prohibitive at their scale.

However, to ensure the success of the sharding process, Notion needed to develop a good sharding strategy.

Some key considerations included:

Notion's data model revolves around the concept of blocks, where each item on a Notion page is represented as a block. Larger blocks can be composed of smaller blocks, forming a hierarchical structure.

The Block table emerged as the top candidate for sharding due to its significance in Notion's data model.

However, the Block table had dependencies on other tables, such as Workspace and Discussions. To maintain data integrity and avoid complex cross-shard queries (which can impact performance), Notion decided to shard all tables that were transitively related to the Block table.

A good sharding key is critical for efficient sharding.

Since Notion is a team-based product where a Block belongs to a Workspace, they decided to use the Workspace ID as the partitioning key.

This decision aimed to minimize cross-shard joins when fetching data, as blocks associated with the same Workspace would be stored within the same shard.

Determining the optimal number of shards was another critical decision because it directly impacted Notion's scalability. The goal was to accommodate the existing data volume while considering a 2-year usage projection.

After analysis, Notion arrived at the following configuration:

480 shards were distributed across 32 nodes, resulting in 15 shards per node. This approach aligned with the fixed number of shards strategy, where the number of shards is predetermined in advance.

An upper bound storage limit of 500 GB per table.

Ultimately, Notion pulled off a successful migration to the sharded database. A few valuable lessons they learned in the process were as follows:

Premature optimization is bad. However, waiting too long before sharding can also create constraints.

Aiming for a zero downtime migration is critical for a good user experience.

Choosing the appropriate sharding key is the most important ingredient for a favorable outcome.

Discord, the social platform for instant messaging, had an interesting problem with its database sharding that is worth discussing.

In 2017, Discord was storing billions of messages from users worldwide and decided to migrate from MongoDB to Cassandra in pursuit of a scalable, fault-tolerant, and low-maintenance database solution.

As Discord's user base and message volume grew over the next few years, they found themselves storing trillions of messages. Their database cluster expanded from 12 to 177 Cassandra nodes. However, despite the increased number of nodes, the cluster encountered severe performance issues.

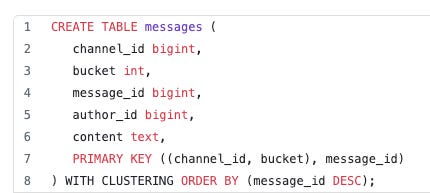

While several factors contributed to the performance degradation, the primary reason was Discord's sharding strategy.

In their database schema, every message belonged to a specific channel and was stored in a table called "messages." The messages table was partitioned based on two fields: "channel_id" and "bucket." The "bucket" field represented a static time window to which the message belonged.

The implication was that all messages within a given channel and period (bucket) were stored on the same partition. Consequently, a popular Discord server with hundreds of thousands of active users could potentially generate a massive volume of messages in a short time, overwhelming a particular shard.

Since Cassandra’s LSM-Tree structure makes read operations typically more expensive than writes, concurrent reads in high-volume Discord channels could create hotspots on specific shards. These hotspots led to cascading latency issues across the entire database cluster, ultimately impacting the end-user experience.

To address these challenges, Discord made several changes to its architecture, including:

Migration to ScyllaDB: Discord migrated from Cassandra to ScyllaDB, a Cassandra-compatible database that promised better performance and resource isolation.

Optimizing Data Access: Discord introduced intermediary services called data services between its API and the database clusters. These services implemented request coalescing and consistent hash-based routing to minimize the load on the database and distribute the traffic more evenly across shards.

Discord’s experience highlights that a good sharding strategy under a specific access pattern can create unexpected performance problems in an application. By optimizing its sharding strategy and data access patterns, Discord successfully mitigated the hotspot issues and improved the performance and scalability of its message storage system.

In this article, we’ve explored database sharding in great detail, covering it from various aspects.

Here’s a quick recap of the main points:

Sharding Fundamentals: Database sharding is a technique for horizontally scaling a database by partitioning it across multiple nodes.

Sharding Strategies: There are three main types of sharding strategies: range-based, key or hash-based, and directory-based sharding. Each strategy has advantages and disadvantages, with hash-based sharding being the most commonly used approach due to its ability to evenly distribute data across shards.

Shard Key Selection: Database designers should consider factors such as cardinality, frequency, and monotonic change when selecting the shard key. A well-chosen shard key is crucial to ensure even distribution and minimize hotspots.

Shard Rebalancing: The database is not static and keeps changing, resulting in the need to rebalance the shards. Various approaches such as fixed partitioning and dynamic sharding can be employed to handle the rebalancing.

Request Routing: There are multiple approaches to route requests to the appropriate shard: partition-aware client, central router, and partition-aware nodes.

MongoDB’s Sharding Architecture: It consists of a central router and an independent configuration server for routing the requests to the correct shard.

Real-World Case Studies: Notion’s journey from a monolithic database to a sharded architecture highlighted the importance of sharding to support rapid growth. Discord’s experience demonstrated how a sharding strategy can result in hotspots due to specific access patterns.

References: