Microservices architecture promotes the development of independent services. However, these services still need to communicate with each other to function as a cohesive system.

Getting the communication right between microservices is often a challenge. There are two primary reasons for this:

When microservices communicate over a network, they face inherent challenges associated with inter-process communication.

Developers often choose a communication pattern without carefully considering the specific needs of the problem. This can lead to suboptimal performance and scalability.

In this post, we explore various communication patterns for microservices and discuss their strengths, weaknesses, and ideal use cases.

But first, let’s look at the key challenges associated with microservice communication.

When two microservices talk to each other, the communication takes place between separate processes often across a network.

This inter-process communication is fundamentally different from method calls between objects within a single process.

There are multiple challenges related to performance, managing change, and error handling.

When a method is invoked within the same process, the compiler and runtime can optimize the call to improve performance.

One common optimization technique is method inlining, where the compiler replaces the method call with the actual code of the method. This eliminates the overhead associated with the function call, such as jumping to the method’s memory address.

In contrast, when a method is invoked across process boundaries, the call involves sending packets over the network, even if both processes are located within the same data center.

This introduces significant latency compared to in-process calls. For reference, a single network round-trip for a packet is typically measured in milliseconds, which is orders of magnitude slower than the overhead of an in-process method call.

The size of the payload is also a concern with inter-process calls.

The in-process method calls pass parameters by references. In other words, only a pointer to the memory location of the data is passed. The data structure does not need to be moved or copied.

However, when making calls between microservices over a network, the data being passed needs to be serialized into a format suitable for transmission. On the receiving end, the serialized data must be deserialized back into its original form before it can be used.

Given these factors, it is more acceptable to make a large number of in-process API calls compared to inter-process API calls.

In an application that uses in-process method calls, it’s relatively straightforward to change a method’s signature. The interface and the code are packaged together, and modern IDEs can often handle the refactoring automatically, updating all the necessary references.

However, modifying an interface in microservice communication is always tricky.

If the changes to an interface are not backward-compatible, we need a lockstep deployment with the consumers of that interface. Coordinating such deployments can be complex and time-consuming, especially in large-scale systems with numerous dependencies.

An alternative approach is to support multiple versions of the interface simultaneously. However, this approach comes with its own set of challenges, such as maintaining and testing multiple versions of the interface.

While developers are not keen on dealing with errors, they are relatively easy to handle within a process boundary. Even if the errors are catastrophic, developers can propagate them up the call stack.

In a distributed system, error handling becomes more complex. Since microservices communicate over a network, a variety of error scenarios need to be considered:

Network timeouts

Unavailable services

Connection issues

Containers going down due to resource constraints

Data center outages

To effectively handle these diverse error scenarios, microservice communication requires a richer set of rules and conventions to describe an error. Without these rules, the calling service can find it difficult to take appropriate action.

For example, the HTTP protocol provides a good example of how errors can be communicated effectively.

HTTP defines a set of status codes that indicate the outcome of a request. The 400 and 500 series status codes are reserved for errors. The 400 series indicates that the error is related to the client’s request. On the other hand, the 500 series signifies that the error occurred on the server side or in a downstream service.

Microservices can employ various communication styles to interact with each other, enabling them to work together as a cohesive system.

However, having too many choices can lead to confusion and complexity in the architecture.

It’s crucial to understand the different communication patterns and their suitability for specific use cases.

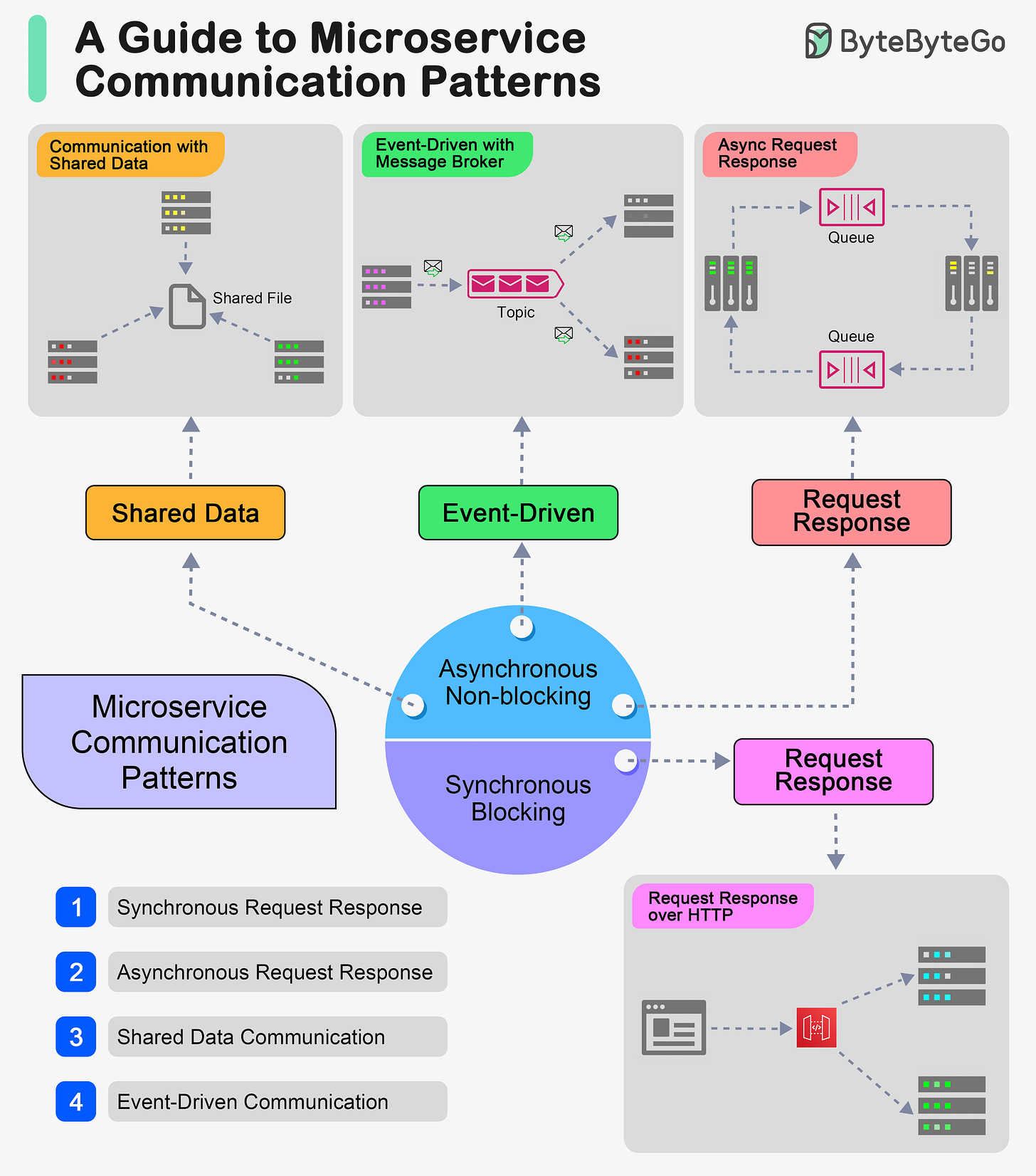

At a high level, we can categorize microservice communication patterns into two main types:

Synchronous Blocking Communication

Asynchronous Non-blocking Communication

Let’s dive deeper into each category and explore the specific patterns within them.

In the synchronous blocking approach, one microservice sends a request to another microservice and remains blocked until it receives the response or encounters an error.

The diagram below shows a basic example.

Since the caller waits for the response, every synchronous blocking call follows the request-response model.

The main advantage of the pattern is its simplicity and familiarity to most developers, as it aligns with the traditional synchronous programming style where each line of code executes sequentially.

However, the synchronous blocking approach has two main drawbacks:

Temporal Coupling: There is a two-way temporal coupling between communicating microservices. This coupling exists not just between the services but also between specific instances of those services. The response is sent over the same inbound network connection opened by the caller. For example, if the Payment Service wants to send a response to the Order Service, but if the upstream service instance dies before receiving the response, the response will get lost.

Cascading Performance Issues: Synchronous blocking calls are vulnerable to cascading performance problems. If the downstream microservice responds slowly, the calling service will be blocked for an extended period. In other words, if the Payment Service experiences a high load and performs poorly, the Order Service will also suffer a dip in performance.

When client applications need to query data for a real-time user interface, the synchronous blocking pattern is often the go-to choice. In this scenario, the client sends a request to the server and waits for the response before updating the UI. This ensures that the user sees the most up-to-date information.

REST is a popular architectural style for implementing request/response communication. It leverages the HTTP protocol and its methods (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE) to enable simpler and direct communication between the clients and various microservices.

The diagram below shows the synchronous request-response approach.

While the synchronous blocking pattern has its merits, it can become an anti-pattern when applied in the wrong context.

One common pitfall is creating long chains of synchronous calls between microservices. In such a scenario, if any single service in the chain experiences an issue or becomes unresponsive, the entire operation can fail, leading to a cascading effect.

Moreover, excessive blocking calls can lead to resource contention. Each blocked call holds onto resources such as threads or database connections until it receives the response. If multiple services are waiting for responses simultaneously, it can strain the system’s resources and degrade performance.

The diagram below shows such a chain of requests where each service waits for the response from its downstream service.

In an asynchronous, non-blocking communication pattern, the calling microservice sends a request to another microservice without waiting for an immediate response. The caller isn’t blocked and can continue processing other requests while the receiving microservice handles the request.

There are three main patterns of communication in this approach.

Communication through common data

Request-Response

Event-driven interaction

The data-sharing pattern is one of the most common inter-process communication patterns. However, it’s largely missed because the communication is indirect and not immediately apparent.

In this pattern, one microservice writes data to a specific location, and another reads and processes that data. For example, a microservice might drop a file in a designated directory, and another microservice picks up that file for further processing.

The diagram below shows this approach.

The reliability of the communication in the data-sharing pattern depends on the reliability of the underlying data store. If the data store is highly available and fault-tolerant, the communication between the services will be more reliable.

The main advantage of this pattern is its simplicity. It can be used by any system capable of reading from and writing to a file or a database, making it an ideal choice for integrating with legacy systems that may not support modern communication protocols. Additionally, this pattern can handle large data volumes efficiently, such as exchanging gigabyte-sized files or millions of records between microservices.

However, the data-sharing pattern has a significant drawback: high latency. The downstream microservice learns about new data through a polling mechanism or a periodically scheduled job. As a result, this pattern may not be suitable for scenarios that require low-latency communication between microservices.

While the synchronous blocking approach is commonly used for request-response calls between microservices, it’s also possible to implement the same pattern using an asynchronous non-blocking approach.

In an asynchronous non-blocking request-response pattern, the receiving microservice needs to explicitly know the destination for sending the response. This is where message queues play a crucial role.

Message queues offer an additional benefit by allowing multiple requests to be buffered up, waiting to be handled. This is useful in situations where requests cannot be processed fast enough by the receiving microservice.

It’s important to note that there is no temporal coupling between services in this pattern.

Therefore, the microservice receiving the response must be able to correlate it with the original request. This can be challenging because a significant amount of time may have passed, and the response may not come back to the same instance of the microservice that sent the request. An ideal solution is to use a database that is accessible to all instances of the service to keep track of the requests.

In the event-driven communication pattern, a microservice doesn’t directly request another microservice to perform some action. Instead, it emits events that other microservices may or may not consume.

This pattern involves two main aspects:

A mechanism for microservices to emit events.

A way for consumers to discover that events have occurred.

Message brokers like RabbitMQ are well-suited for handling both of these aspects. Producers use an API to push events to the broker, while the broker manages subscriptions, notifying consumers when an event arrives.

But what is an event?

An event is a fact or a statement about something that has happened within the context of the microservice that emits the event. In the event-driven pattern, the event is broadcast by encapsulating it into a message. The message serves as the medium, and the event is the payload.

The microservice emitting the event is unaware of the existence or the intent of other microservices that may react to the event.

This approach results in an inversion of responsibility. For example, in the diagram above, the responsibility of determining whether a customer should receive a notification is shifted from the Order Service to the Customer Notification Service.

In essence, the event-emitting microservice leaves it up to the recipients to decide how to handle a particular event.

The event-driven pattern is useful in scenarios where a microservice needs to broadcast information without specifying what downstream microservices should do with that information. This promotes loose coupling between services.

However, this pattern can also introduce new sources of complexity, such as:

Ensuring reliable event delivery and processing.

Handling event ordering and consistency.

Managing event schema evolution.

Debugging and tracing event-driven interactions.

After exploring the various communication patterns in microservices architecture, the next step is to choose the appropriate technology to implement these patterns. There are several options available, such as SOAP, REST, gRPC, and others.

When selecting a technology for microservice communication, there are several key requirements to consider:

Backward Compatibility: The chosen technology should make it easy to support backward compatibility when making changes to a microservice. This ensures that updates to the service don’t impact the existing consumers.

Explicit Interface: The interface of the service should be explicit to the outside world. This is crucial for communicating the functionalities and capabilities supported by the microservice to its consumers.

Simplicity for Consumers: The technology should make it simple for consumers to interact with the microservice. Consumers should be free to choose a particular technology or have access to easy-to-use client libraries. However, this requirement needs to be balanced with the level of coupling from a technology perspective.

Encapsulation of Internal Details: The chosen technology should provide a clear separation between the service’s interface and its internal workings.

Some of the most popular technology choices for enabling the various microservice communication patterns are as follows:

Remote Procedure Calls

REST

Message Brokers

Remote Procedure Call (RPC) is a technique that allows a local method call to execute on a remote service hosted elsewhere, making it appear as if the remote service is being called locally.

In the RPC ecosystem, technologies such as SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol) and gRPC require an explicit schema to define the interface of the remote services.

With RPC, the schema is known as the Interface Definition Language (IDL). On the other hand, SOAP uses the Web Service Definition Language (WSDL) to define the structure and functionality of the web service.

Having a well-defined schema brings several benefits to the development process.

It enables the automatic generation of client code, eliminating the need for manual client libraries. Any client, regardless of the programming language or platform, can generate their code based on the service specification.

For example, consider a scenario where a Java service exposes a SOAP interface.

A .NET client can easily consume this service by generating a client stub from the same WSDL file. The generated client code handles the serialization and deserialization of the request and response messages, abstracting away the complexities of the underlying communication protocol.

Representational State Transfer (REST) is an architectural style that provides guidelines for designing networked applications.

At the heart of the REST architecture is the concept of a resource. A resource is any information that can be uniquely identified and accessed through a URL (Uniform Resource Locator). Resources can represent a wide range of entities, such as:

Users

Products

Orders

Collections of other resources

Resources are typically represented using standard data formats like JSON or XML. These formats provide a structured way to exchange data between microservices.

A REST API is designed around the manipulation of resources. It exposes a set of standard HTTP methods clients can use to interact with the resources. The most commonly used HTTP methods in a REST API are:

GET - Retrieves a resource or a collection of resources.

POST - Creates a new resource.

PUT - Updates an existing resource.

DELETE - Deletes a resource.

Message brokers play a crucial role in facilitating asynchronous communication between microservices. They act as middleware, sitting between two processes or microservices, managing the exchange of messages between them.

Instead of one microservice directly communicating with another, it sends a message to the message broker. The message broker then routes the message to the appropriate recipient microservice or microservices based on the subscriptions.

Message brokers typically provide two main communication patterns:

Queues: Queues are used for point-to-point communication. The sender microservice puts a message into a specific queue, and the consumer microservice reads from that queue. This pattern ensures that each message is processed by exactly one consumer.

Topics: Topics enable publish-subscribe communication where multiple consumer microservices can subscribe to a particular topic. When a message is published, each consumer subscribed to a topic receives a copy of that message. This pattern allows for broadcasting messages to multiple recipients.

In a topic-based system, a consumer can represent multiple instances of a microservice modeled as a consumer group.

In this article, we’ve explored various patterns for microservice communication, discussing their advantages and disadvantages.

Here’s a quick recap of the main points:

Microservice communication involves inter-process communication over a network, which presents challenges related to performance, interface modification, and error handling.

There are two main approaches to microservice communication: synchronous blocking and asynchronous non-blocking.

The synchronous blocking approach follows the request-response pattern where one microservice sends a request to another microservice and remains blocked until it receives the response.

The asynchronous non-blocking approach encompasses several patterns - communication through common data, request-response, and event-driven communication.

Choosing the ideal communication technology for a project or application depends on multiple factors and requirements.

Some popular choices for communication between microservices include RPC, REST, and Message Brokers.

However, the most important takeaway is that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. The choice of communication pattern should be based on the specific scenario and requirements within a project, rather than personal preferences or biases.