The complexity of software applications has grown by leaps and bounds over the years.

This has led to a rise in the number of interfaces between various systems, resulting in an ever-growing API footprint.

While APIs have revolutionized the connectivity between systems, the explosion of integrations between clients and servers often leads to maintenance problems. Even minor backend changes take more implementation time since developers must analyze and test more. Despite all the effort, there are still high chances that issues creep into the application.

Refactoring the application interfaces is one way to address growing maintenance costs. However, this is costly, and there’s no guarantee that we won’t encounter similar issues as the system evolves.

What’s the solution to this problem?

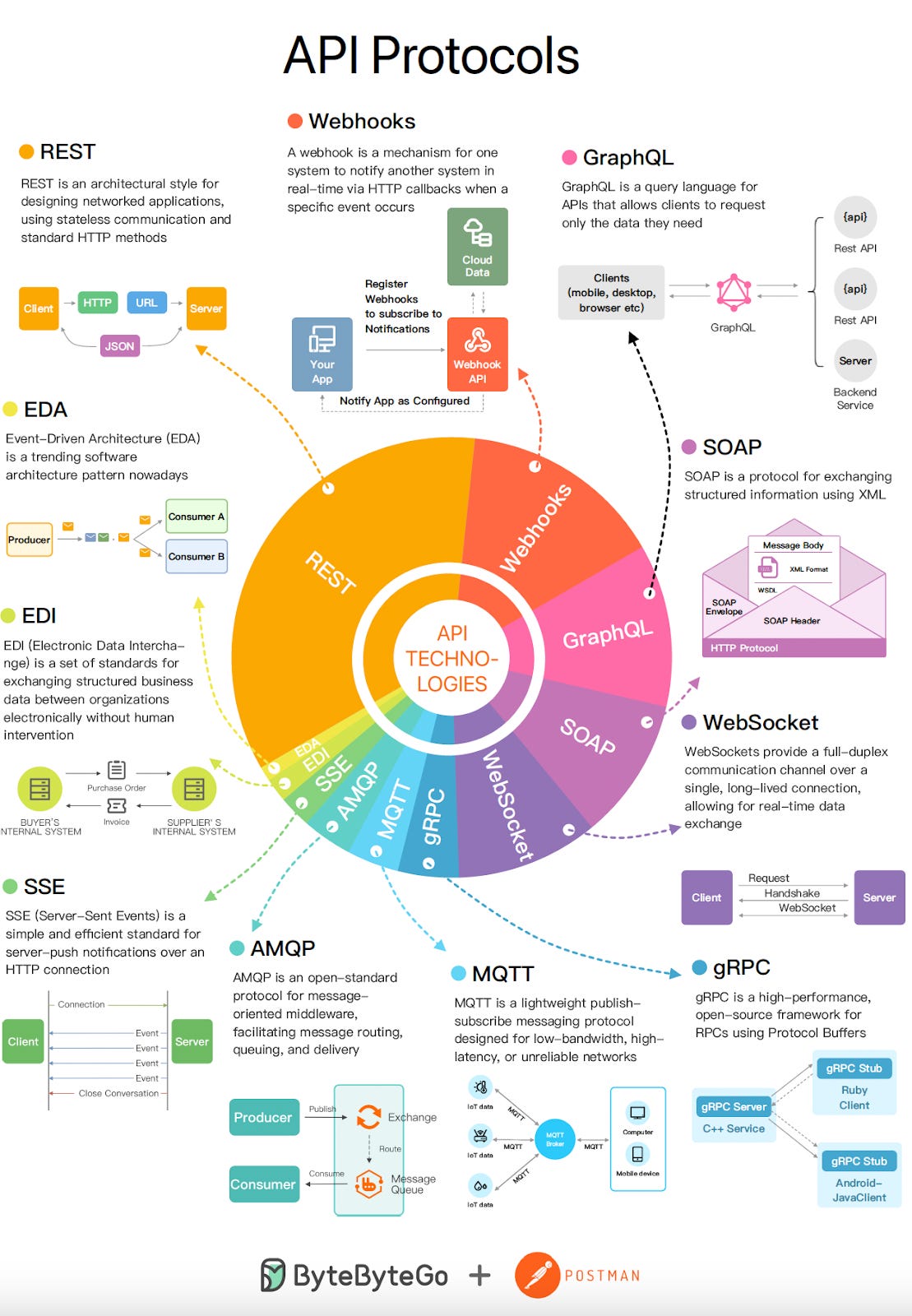

GraphQL is a tool that brings a major change in how clients and servers interact. While it’s not a silver bullet, it can be a sweet spot between a complete application overhaul and doing absolutely nothing

In this issue, we’ll explore GraphQL's features and concepts, compare it to REST API and BFFs, and discuss its advantages and disadvantages.

GraphQL stands for Graph Query Language and is a combination of two things:

An open-source language for querying and manipulating data.

A runtime for fulfilling those queries.

It was initially developed as an internal project at Facebook in 2012. According to Lee Byron, the co-creator of GraphQL, they got the idea when trying to design a native iOS news feed with a traditional REST API.

While using REST APIs for their use case, they encountered several issues:

The API requests had high latency.

Coordination of requests for different models was cumbersome.

Due to API fragmentation, multiple roundtrip requests had to be made on flaky mobile connections.

Changes to the API had to be carefully implemented on the client code to prevent the app from crashing.

API documents were often out of date from the actual implementation.

The goal of overcoming these issues led to the birth of GraphQL.

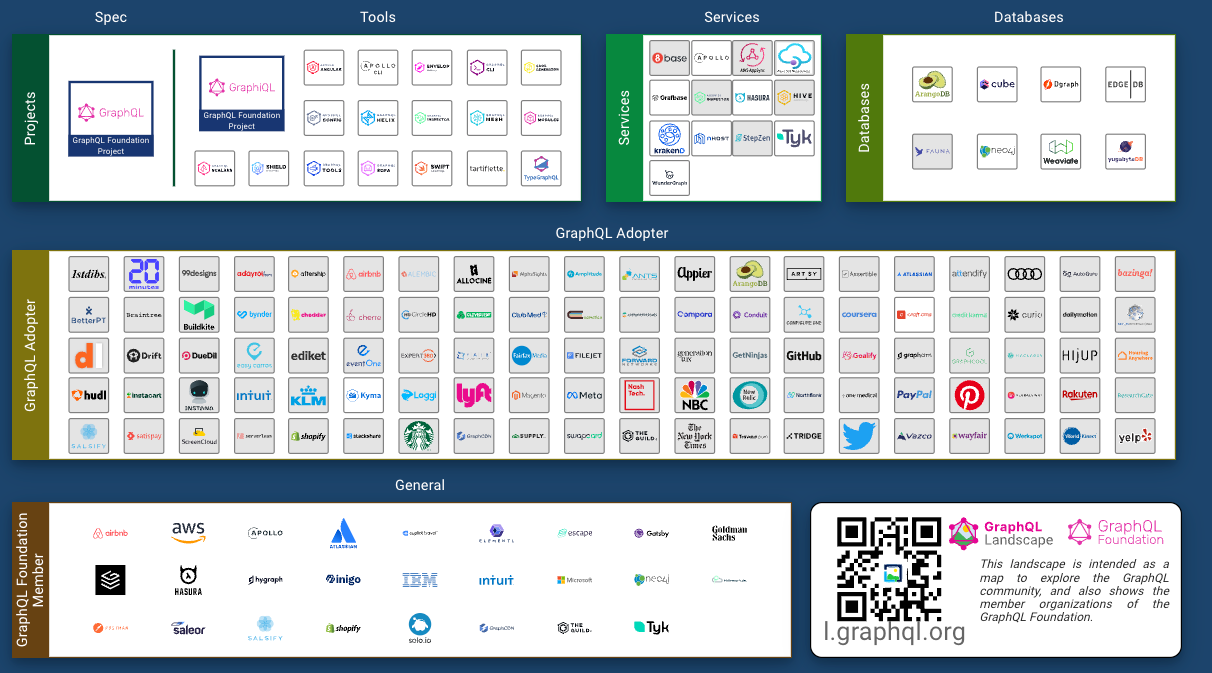

GraphQL was initially an internal project but was publicly released in 2015. In 2018, the project was moved from Facebook to the newly established GraphQL Foundation. Currently, the GraphQL Foundation is hosted by the non-profit Linux Foundation.

Over the years, GraphQL has seen a great deal of adoption across the industry.

Even though the term “query language” makes it sound like SQL, we don’t query typical database tables using GraphQL.

Like REST, GraphQL is a format or structure that defines the contract between the client and the API server. However, it is much more flexible when compared to REST. It is also largely interchangeable with REST.

In a way, GraphQL aims to do what REST has been doing for all these years, but better.

Let’s understand the working on GraphQL on a more conceptual level.

Imagine that there is a vending machine. To get one item from the vending machine, we press a button. To get another item, we press another button. Similarly, to get five items, we have to press five different buttons.

At a high level, this is how the REST approach works. For every piece of data, the client makes a new request. This process is cumbersome when we need to aggregate data from multiple entities within our system.

To get around this problem, developers usually choose one of the two options:

The aggregation of data is done at the client layer.

Special REST endpoints are created that aggregate data at the service layer and expose a single interface for the client.

These special endpoints are the equivalent of a vending machine with special buttons for a particular combination of items. Each special button handles a particular combination of items.

But how many special buttons would we create?

There might be hundreds of item combinations possible. Even if we create a hundred special buttons, we can never be sure that there won’t be a new customer looking for a specific combination.

This approach is not scalable.

But what if the vending machine supported an option to choose multiple items in one go by pressing a combination of buttons?

It’s the equivalent of the user telling the machine exactly what it needs. Once the order is placed, the user gets everything they asked for in one go.

This is the essence of how GraphQL works.

The client specifies exactly what it needs, and the GraphQL runtime provides everything in one go. There’s no need to make multiple requests to collect data.

Before we go further, let’s look at some important features of GraphQL.

In GraphQL, clients query the server. These queries are declarative.

A typical GraphQL query may look like the example below:

{

book(id: "1") {

title

publishYear

}

}The query is self-explanatory. The client is asking for the book with a specific ID and specifying that it only needs two fields – title and publishYear.

Upon receiving the query, the GraphQL runtime makes sure that only the fields specified in the query are included in the response.

{

"data": {

"book": {

"title": "System Design Interview Volume 2",

"publishYear": 2022

}

}

}Queries in GraphQL are hierarchical. See the example below:

{

book(id: "1") {

title

publishYear

authors {

name

}

}

}Here, the client is asking for the book with an ID of 1. However, along with the book details, the client is also interested in getting the author-related information about the book.

Type safety is an important feature of GraphQL.

In GraphQL, we declare schemas to specify the data model. These schemas are strongly typed and help the server determine whether the client’s query is valid.

See the example below:

type Book {

title: String!

publishYear: Int

price: Float

}Each attribute in the Book entity has a data type. The type system can use primitive types such as numeric integers, booleans, and strings and complex types such as objects.

There are some key concepts to understand when working with GraphQL. Let’s look at the most important ones.

As mentioned earlier, GraphQL has a type system that can be used to define the schema supported by the GraphQL server.

This schema uses a special syntax called the Schema Definition language or SDL.

The example below shows a simple schema for an entity named Author. It contains only one field: the author's name. The ‘!’ mark denotes that the name is a mandatory field.

type Author {

name: String!

}Clients make queries to the GraphQL server. These queries specify the requirements of the client.

If a query is valid, the server responds to the client.

For example, here is a typical GraphQL query to get the details about a book.

{

book(id: "1") {

title

publishYear

}

}As we all know, APIs are used not only to query information but also to update information.

In GraphQL, updates are supported using mutations.

The example below shows a mutation.

mutation {

createBook(title: 'System Design Interview Volume 2', publishYear: "2022") {

name

country

}

}The syntax is quite similar to the query. However, the keyword mutation communicates that the client wants to update or create a record.

Many situations require real-time connection between the client and the server. In GraphQL, this is supported by subscriptions.

Subscriptions don’t follow the typical request-response cycle. When a client subscribes to an event, it holds the connection to the server. The server pushes the data to the client whenever a particular event occurs.

In GraphQL, subscriptions are written using the same format as queries and mutations.

subscription {

newAuthor {

name

country

}

}In the above example, once the client sends a subscription request to the server, a connection is opened between them. Whenever a new mutation results in the creation of a new author, the server sends the specified data to the client.

{

"newAuthor": {

"name": "John Doe",

"country": "USA"

}

}The GraphQL server is the heart of a GraphQL-based system and can be used to support different architectural patterns.

This is the most common approach for greenfield projects.

We start with a single web server that implements the GraphQL specification. When a query arrives at the GraphQL server, it resolves the query. This involves reading the query’s payload, fetching the required information from the database, and constructing the response for the client.

The diagram below shows this approach at a high level:

GraphQL is database-agnostic. It can be used with SQL databases like Postgres and MySQL and NoSQL ones like MongoDB.

A major use case of GraphQL is to integrate multiple existing systems behind a single, unified GraphQL API.

Using this approach, we can develop client applications that talk to the GraphQL server. The server is responsible for fetching the data from the existing systems and constructing the required response.

See the diagram below for reference:

GraphQL and REST are two approaches to building APIs, each with strengths and weaknesses. REST has been the dominant API architectural pattern for many years, relying on multiple endpoints where each endpoint delivers a fixed data structure.

However, REST APIs are not flexible and don’t adapt well to the changing client requirements.

With REST API, it’s common to overfetch data.

This happens because each endpoint has a specific schema in REST. Even if the client requires only one field, the API will return all the fields.

The bigger problem with REST is underfetching data.

A single REST API endpoint does not provide the complete data the client needs. We make an API call, get some response, and use that response to make another API call to get the rest of the information.

Depending on the design, there can be multiple calls to accumulate the required data, resulting in the n + 1 problem.

The diagram below shows an example of a REST approach in which we make two separate calls to fetch the book and the author's details.

GraphQL uses a single endpoint, allowing clients to send flexible queries that specify the exact data requirements. This approach reduces data usage and speeds up development by eliminating the need for multiple round-trips to the servers.

The Backend-For-Frontend (BFF) pattern involves creating dedicated backend services tailored to the specific needs of each frontend client or application. This gives the frontend teams more autonomy and flexibility to customize the API layer.

The below diagram shows the BFF pattern.

Organizations such as Netflix and Airbnb adopted BFFs to support the varied requirements of different client devices. However, the BFF pattern has some drawbacks that can lead to “BFF sprawl.”

Each BFF requires independent development and maintenance, adding overhead costs.

BFFs can still suffer from overfetching and underfetching data, requiring multiple requests to get data.

As the number of clients grows, managing many BFFs becomes complex and prone to duplication. This is the same as creating numerous special buttons in our vending machine example.

As we’ve seen earlier, GraphQL can replace the need for BFFs by allowing clients to query what they need from a single, unified endpoint.

The standard GraphQL setup with a single GraphQL server can run into some issues, such as:

Schema Complexity and Organization: As the GraphQL schema grows in size and complexity, it can become difficult to manage as a single monolithic schema.

Team Scalability: If there’s a monolithic GraphQL server, a single team may become a development bottleneck as they have to implement all new features.

Lack of Domain Authority: A unified schema becomes difficult to manage. Multiple teams may want to make schema changes but they don’t have sufficient domain knowledge about all the functionalities handled by it. This can result in a bigger impact radius, negating the advantage of service-oriented architecture.

To solve these issues, large organizations often adopt GraphQL Federation.

GraphQL Federation is an architectural pattern that allows us to decompose the monolithic schema into smaller, more focused subgraphs that can be developed and deployed independently. Each subgraph handles a specific domain or service boundary within the overall application.

The diagram below shows the high-level architecture of a GraphQL Federated Gateway.

For example, consider an e-commerce application with services for products, reviews, and users. With federation, we could have three subgraphs:

A products subgraph that defines types like Product, Category, Inventory, etc.

A reviews subgraph that defines types like Reviews, Ratings, etc.

A user subgraph that defines types like User, Account, Preferences, etc.

Each subgraph has a focused schema containing the types and fields relevant to its domain. The schema registry acts as the central repository for all the individual schemas, allowing for team-specific ownership. For example, the products team can completely own the Product type without worrying about breaking changes to other types.

The federation gateway is responsible for stitching these subgraphs into a unified schema (also known as the supergraph) and executing queries across them. To the client, it still looks like one coherent schema, but the implementation is decoupled behind the scenes.

One of the common questions developers have while learning about GraphQL is how they can adopt GraphQL.

Typically, teams begin their GraphQL journey with a basic architecture where a client application queries a single GraphQL server. The server distributes those requests to backing data sources and returns the data.

The diagram below shows this approach:

However, multiple sub-patterns are possible in the context of the basic architecture.

Often, the client teams are eager to take advantage of GraphQL’s capabilities around data fetching. Therefore, they implement a GraphQL API to wrap existing APIs behind a single GraphQL endpoint.

See the diagram below:

This approach improves the developer experience. However, the client still bears the performance costs since it makes multiple requests to various services to gather data from different APIs.

As we saw earlier, BFFs attempt to solve the problem of requiring different clients (such as web, mobile, and so on) to interact with a monolithic and general-purpose API.

BFFs add a new layer where each client has a dedicated BFF service that receives the client’s requests. For such cases, GraphQL can be a natural fit to build a client-focused intermediary layer.

This approach improves the developer experience and overcomes the performance issues for the client. However, there’s a tradeoff in building and maintaining BFFs. Also, there is a chance of duplication of effort between teams.

This is also a common approach to building GraphQL applications.

Here, multiple teams share one codebase for a GraphQL server used by several clients. Alternatively, a single team owns a GraphQL API that is accessed by multiple client teams.

The diagram below shows this arrangement:

This approach creates challenges around ownership of different parts of the schema. Portions of the graph may suit the needs of a particular client, while others may need to find workarounds.

Consolidating the multiple graphs into a supergraph is a good way to deal with the problems of other patterns.

At a fundamental level, the supergraph requires the organization to have one unified graph instead of multiple graphs created and managed by different teams. However, the implementation of the common graph should be federated across multiple teams to maintain domain ownership.

A federation-driven supergraph architecture is made up of two parts:

A collection of subgraph services that each define a distinct GraphQL schema. Each subgraph implements only part of the graph.

A router that composes the distinct schemas into a supergraph and executes queries across the services in the graph.

The diagram below shows what the supergrapproach looks like:

This approach provides a single entry point for the client, similar to a basic GraphQL server. However, it fulfills the query by getting the data from multiple subgraphs.

Some best practices to follow developing with GraphQL are as follows:

Schema Design: Keep the schema simple, straightforward, and easy to understand for the clients and developers. Use clean and concise naming conventions for types and fields. Also, avoid unnecessary nesting and circular dependencies in the schema.

Query Optimization: Avoid overfetching data by carefully considering the fields requested in the queries. Implement server-side batching and caching to minimize repeated requests to the backend services.

Versioning: Avoid versioning if possible and instead design the schema to allow for continuous evaluation. Use deprecation, nullability, and default values to make non-breaking changes.

Security: Just like we do with REST APIs, adhere to security best practices such as authorization, authentication, rate limiting, etc.

Tooling: Leverage GraphQL IDEs like GraphiQL for schema development, testing, and documentation. Also, use well-established server libraries to simplify implementation.

GraphQL is an open-source query language and runtime for APIs developed by Facebook.

The key characteristics of GraphQL that we have discussed in this article are as follows:

It is strongly typed, allowing for clear and helpful error messages.

The GraphQL queries are declarative, so clients specify exactly what data they need.

It enables fetching related resources in a single request, avoiding over and under-fetching data.

GraphQL uses a type system to define the capabilities of an API. The main building blocks are:

Schema: Defines the data types, relationships, and operations allowed

Fields: Units of data that can be queried on an object.

Mutations: Operations for creating, updating, and deleting data

Subscriptions: Real-time updates pushed from server to clients

GraphQL provides some key benefits as compared to typical REST APIs or Backend-for-Frontends (BFFs). However, a monolithic GraphQL server can also create ownership issues due to which enterprises slowly move towards GraphQL Federation to manage the various subgraphs.

In summary, GraphQL offers a powerful and flexible approach to building APIs. While it has a learning curve and isn't ideal for every scenario, its advantages around precision querying, minimizing roundtrips, and enabling great tooling make it a compelling choice for many applications.