What has powered the incredible growth of the World Wide Web?

There are several factors, but HTTP or Hypertext Transfer Protocol has played a fundamental role.

Once upon a time, the name may have sounded like a perfect choice. After all, the initial goal of HTTP was to transfer hypertext documents. These are documents that contain links to other documents.

However, developers soon realized that HTTP can also help transfer other content types, such as images and videos. Over the years, HTTP has become critical to the existence and growth of the web.

In today’s deep dive, we’ll unravel the evolution of HTTP, from its humble beginnings with HTTP1 to the latest advancements of HTTP2 and HTTP3. We’ll look at how each version addressed the limitations of its predecessor, improving performance, security, and user experience.

By the end of this article, you’ll have a solid understanding of the key differences between HTTP1, HTTP2, and HTTP3, helping you make informed decisions when designing web applications.

HTTP/1 was introduced in 1996. Before that, there was HTTP/0.9, a simple protocol that only supported the GET method and had no headers. Only HTML files were included in HTTP responses. There were no HTTP headers and no HTTP status codes.

HTTP/1.0 added headers, status codes, and additional methods such as POST and HEAD. However, HTTP/1 still had limitations. For example, each request-response pair needed a new TCP connection

In 1997, HTTP/1.1 was released to address the limitations of HTTP/1. Generally speaking, HTTP/1.1 is the definitive version of HTTP1. This version powered the growth of the World Wide Web and is still used heavily despite being over 25 years old.

What contributed to its incredible longevity?

There were a few important features that made it so successful.

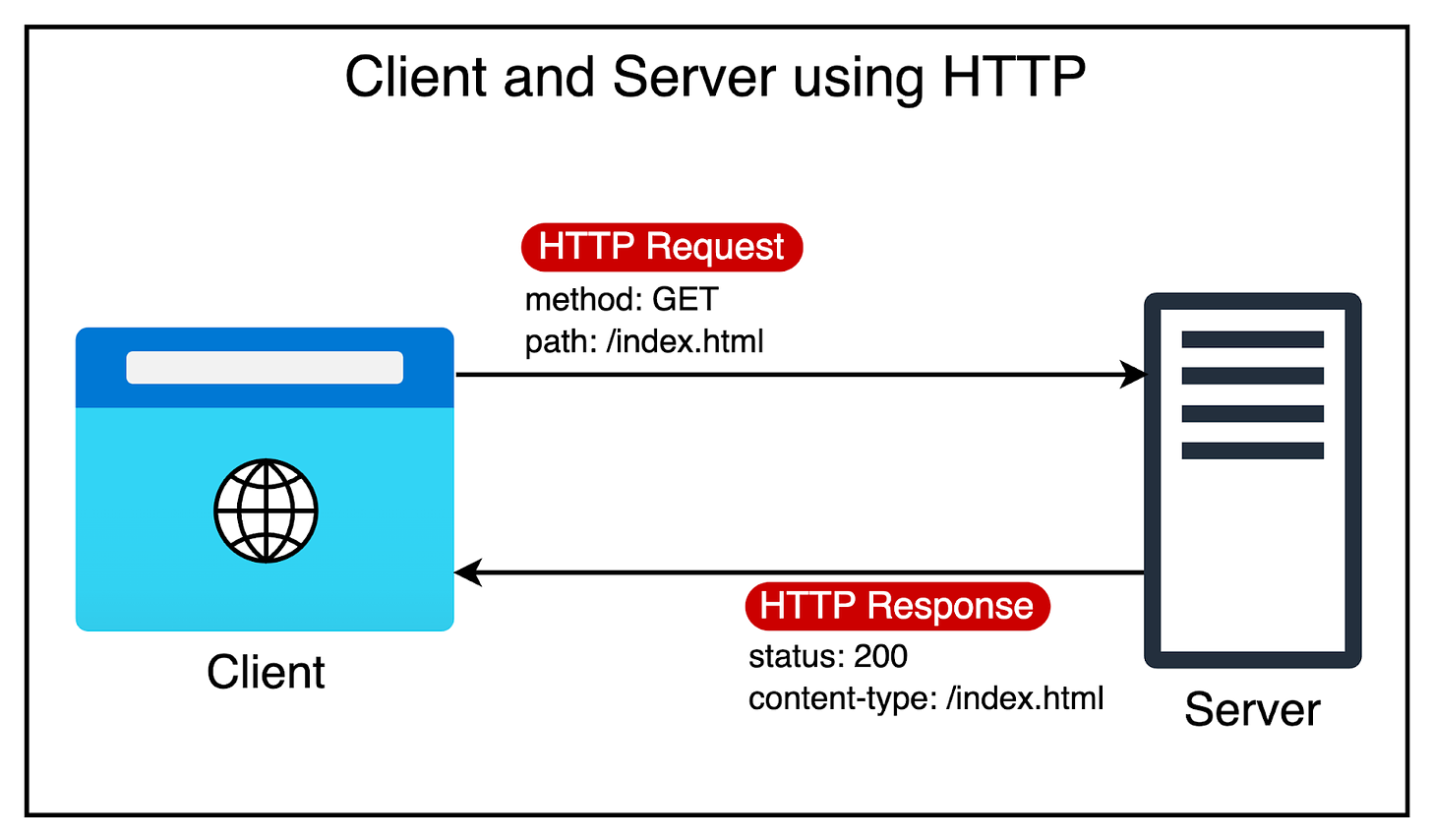

As mentioned, HTTP started as a single request-response protocol.

A client opens a connection to the server, makes a request, and gets the response. The connection is then closed. If there’s a second request, the cycle repeats. The same cycle repeats for subsequent requests.

It’s like a busy restaurant where a single waiter handles all orders. For each customer, the waiter takes the order, goes to the kitchen, prepares the food, and then delivers it to the customer’s table. Only then does the waiter move on to the next customer.

As the web became more media-oriented, closing the connection constantly after every response proved wasteful. If a web page contains multiple resources that have to be fetched, you would have to open and close the connection multiple times.

Since HTTP/1 was built on top of TCP (Transmission Control Protocol), every new connection meant going through the 3-way handshake process.

HTTP/1.1 got rid of this extra overhead by supporting persistent connections. It assumed that a TCP connection must be kept open unless directly told to close. This meant:

No closing of the connection after every request

No multiple TCP handshakes.

The diagram below shows the difference between multiple connections and persistent connections.

HTTP/1.1 also introduced the concept of pipelining.

The idea was to allow clients to send multiple requests over a single TCP connection without waiting for corresponding responses. For example, when the browser sees that it needs two images to render a web page, it can request them one after the other.

The below diagram explains the concept of pipelining in more detail.

Pipelining further improved performance by reducing the latency for each response before sending the next request. However, pipelining had some limitations around head-of-line blocking that we will discuss shortly.

HTTP/1.1 introduced chunked transfer encoding that allowed servers to send responses in smaller chunks rather than waiting for the entire response to be generated.

This enabled faster initial page rendering and improved the user experience, particularly for large or dynamically generated content.

HTTP/1.1 introduced sophisticated caching mechanisms and conditional requests.

It added headers like Cache-Control and ETag, which allowed clients and servers to better manage cached content and reduce unnecessary data transfers.

Conditional requests, using headers like If-Modified-Since and If-None-Match, enabled clients to request resources only if they had been modified since a previous request, saving bandwidth and improving performance.

There’s no doubt that HTTP/1.1 was game-changing and enabled the amazing growth trajectory of the web over the last 20+ years.

However, the web has also evolved considerably since the time HTTP/1.1 was launched.

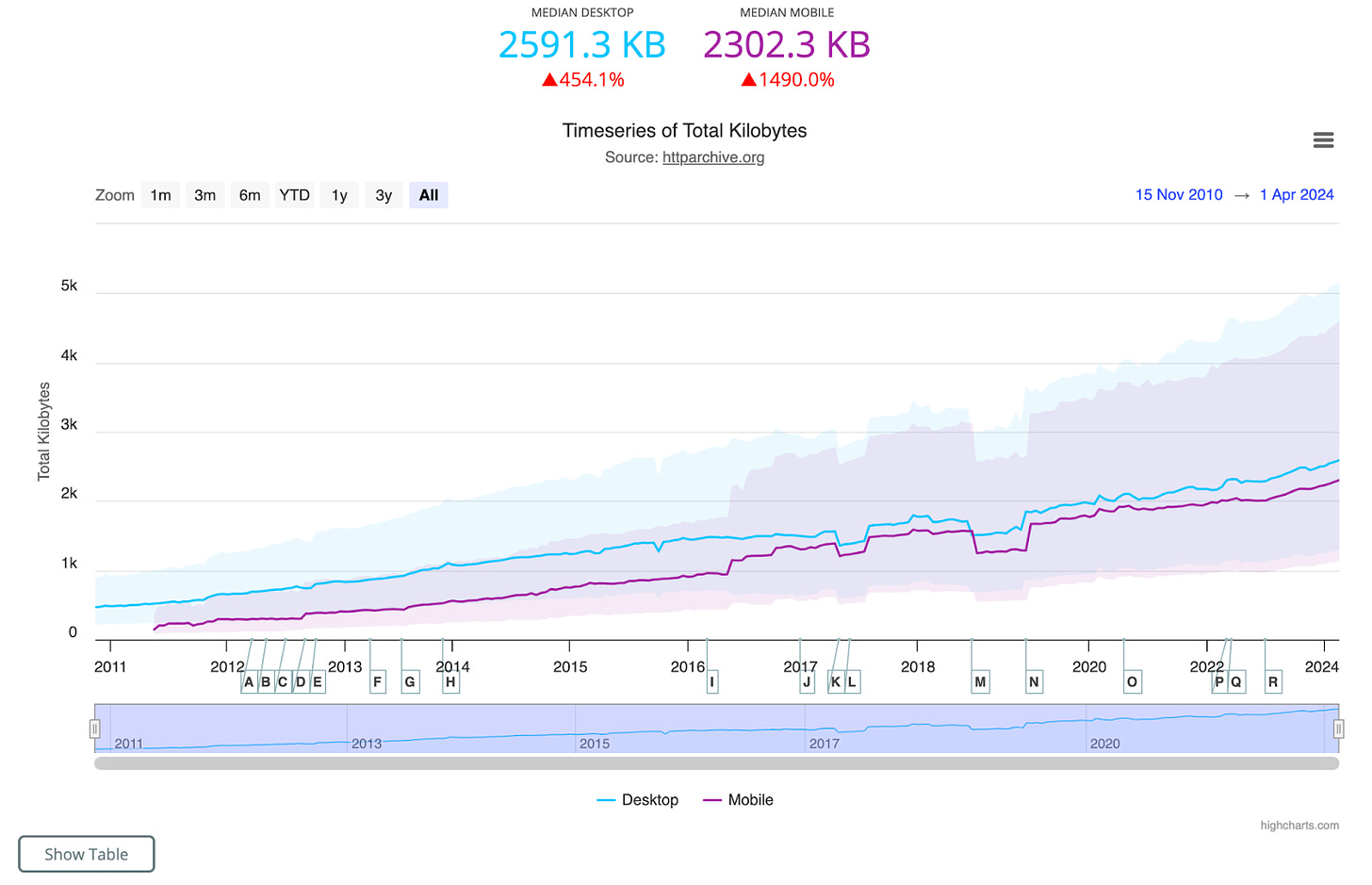

Websites have grown in size, with more resources to download and more data to be transferred over the network. According to the HTTP Archive, the average website these days requests around 80 to 90 resources and downloads nearly 2 MB of data.

The next graph shows the steady growth of website size over the last 10+ years.

This growth exposed a fundamental performance problem with HTTP/1.1.

The diagram below explains the problem visually.

Let’s understand what’s happening over here:

The client requests the server for an HTML page that contains two images. Assume that the roundtrip takes 100 milliseconds.

After receiving the HTML page, the browser requests the first image. This adds another 100 milliseconds to the overall request.

Moving on, the browser requests the second image, adding another 100 milliseconds.

After fetching both images, the browser finishes rendering the page.

As you can notice, latency can become a big problem with HTTP/1.1 as the number of assets on your web page grows.

There were a couple of workarounds to solve this issue, such as:

Imagine the same request-response flow with pipelining in place.

As you can see, pipelining saves 100 milliseconds because the client can request both images one after the other without waiting for a response.

Unfortunately, pipelining wasn’t well supported by web browsers due to implementation difficulties, and as a result, it was rarely used.

Also, pipelining was still prone to another problem known as head-of-line (HOL) blocking, in which a blocked request at the head of the queue can block all the requests behind it.

HOL blocking was solved to some extent by supporting multiple HTTP connections per domain. Most popular browsers support a maximum of six connections per domain.

However, for modern sites, this is not enough.

As a workaround, many websites serve static assets such as images, CSS, and JavaScript from subdomains. With each new subdomain, they get six more connections to handle the requests.

This technique is known as Domain Sharding. For reference, a website like Stackoverflow loads the various assets from different domains as shown below:

While Domain Sharding sounds like a perfect solution to the problems of HTTP1, it also has downsides.

Starting a TCP connection takes time (due to the 3-way TCP handshake), and maintaining it requires extra memory and processing. When multiple HTTP connections are used, both the client and server have to pay this price.

To top it up, TCP also follows a slow-start algorithm.

For reference, slow start is a congestion control algorithm. Here’s how it works:

The sender starts by sending a small number of packets.

For each packet that is successfully acknowledged by the receiver, the sender increases the number of packets in the next round. This increase is exponential.

The sender keeps increasing the number of packets sent until it reaches a certain limit, called the congestion window.

If the congestion window is reached without packet loss, the sender knows that the network can handle the current amount of data.

If a packet is lost or acknowledgment is delayed, the sender assumes that the network is congested and reduces the number of packets sent to avoid overwhelming the network.

By starting slowly and gradually increasing the data flow, the slow-start algorithm helps prevent network congestion.

However, since all packets need to be acknowledged, it may take several TCP acknowledgments before the full HTTP request and response messages can be sent over the connection.

The next workaround was to make fewer requests.

This is done in two main ways:

Browsers cache assets all the time to reduce costly network calls.

Assets are bundled into combined files.

For example, images are bundled using a technique known as spriting. Rather than using one file for each icon, spriting helps bundle them into one large image file and uses CSS to pull out sections of the image to re-create the individual images.

In the case of CSS and JavaScript, multiple files are concatenated into fewer files. Also, you minimize them by removing whitespaces, comments, and other elements.

However, creating image sprites is costly and requires development effort to rewrite the CSS to load the images correctly, and not all websites use build steps to concatenate the JS and CSS files.

In 2015, HTTP2 was launched to address the specific performance problems with HTTP1.

It brought some major improvements that are as follows:

HTTP1 sends messages in plain-text format, which is readable by humans but requires more processing time for computers to parse and understand.

In contrast, HTTP/2 encodes messages in binary format.

This allows the messages to be divided into smaller units called frames, which are then sent over the TCP connection.

Frames are essentially packets of data, similar to TCP packets. Each frame belongs to a specific stream, which represents a single request-response pair. HTTP2 separates the Data and Header sections of an HTTP request into different frames.

The Data frame contains the actual payload or message content.

The Header frame contains metadata about the request or response, such as the content type, encoding, and cache directives.

This encoding magic is performed by a special component of the protocol known as the Binary Framing Layer.

The Binary Framing Layer is a fundamental component of the HTTP2 protocol. It is responsible for encoding the HTTP messages into binary format, creating the frames, and managing the transmission of frames over the network.

The diagram below explains the concept visually.

By splitting the message into frames, HTTP2 enables more efficient processing and multiplexing of requests and responses. Multiple frames from different streams can be sent over the same TCP connection, allowing for concurrent data transmission.

The good news is that despite the conversion, HTTP2 maintains the same HTTP semantics as HTTP1. In other words, you can have the same HTTP methods and headers, which means that applications created before HTTP2 can continue functioning normally while using the new protocol.

A few important benefits due to the binary format are as follows:

Better efficiency

More compact

Less error-prone when compared to HTTP1, which relied on many “helpers” to deal with whitespaces, capitalization, line endings, etc.

The Binary Framing Layer allows full request and response multiplexing.

This means that clients and servers can now break down an HTTP message into independent frames, interleave them during transmission, and reassemble them on the other side.

The diagram below tries to make things clearer.

It shows how HTTP1 uses three TCP connections to send and receive three requests in parallel.

Request 1 fetches the styles.css.

Request 2 downloads the script.js file.

Lastly, Request 3 gets the image.png file.

On the other hand, HTTP2 allows multiple requests to be in progress at the same time on a single TCP connection. The only difference is that each HTTP request or response uses a different stream (marked in different colors in the diagram)

For reference, streams are made up of frames (such as header frames or data frames), and each frame is labeled to indicate which message it belongs to. As you can see in the diagram, the three requests are sent one after the other, and the responses are sent back simultaneously.

This ensures the connection is not blocked after sending a request until the response is received.

HTTP2 also supports stream prioritization.

The order matters when a website loads a particular asset (HTML, CSS, JS, or some image). For example, if the server sends a large image before the main stylesheet, the page might appear unstyled for a while, leading to a slower perceived load time.

Since HTTP1 followed a single request-response protocol, there was no need for prioritization by the protocol since it was the client’s responsibility.

However, in HTTP2, when you load a web page, the server can send these assets back to the browser in any order, even though it might not be efficient.

Stream prioritization helps developers customize the relative weight of requests (and streams) to optimize performance. The browser can indicate priorities for the respective assets or files, and the server will send more frames for higher-priority requests.

HTTP2 also supports server push.

Since HTTP2 allows multiple concurrent responses to a client’s request, a server can send additional resources to a client along with the requested HTML page.

This is like providing a resource to the client even before the client asks for it explicitly. Hence, the name server push.

From the client’s perspective, they can decide to cache the resource or even decline the resource.

The diagram below shows this process.

In HTTP/1.1, using programs like gzip is quite common for compressing data sent over the network. However, in HTTP1, only the main data is compressed, while the header (which contains information about the data) is sent as plain text.

The reasoning behind this was that since the header is quite small, it doesn’t significantly impact the website’s performance.

However, the rise of modern API-heavy applications means that websites need to call multiple APIs, sending many requests back and forth. With each request, the overall weight of the headers grows heavier.

HTTP2 solves this problem by using a special compression program called HPACK to make the headers smaller.

Here’s how HPACK works:

It looks at the headers and finds ways to make them smaller.

It also remembers the headers that were sent before and uses that information to compress them even more the next time they’re sent.

See the below diagram:

As you can see, the various fields in Request 1 and Request 2 have more or less the same value. Only the path field uses a different value. In other words, HTTP2 leverages HPACK to send only the indexed values required to reconstruct these common fields and just encode the path field for Request 2.

As the web evolved further and web applications became more complex, the limitations of TCP in HTTP2 became increasingly apparent.

Though HTTP2 introduced significant improvements in the form of multiplexing and header compression, its reliance on TCP posed challenges in terms of performance and latency. TCP’s connection-oriented nature, its handling of packet loss, and head-of-line blocking results in slower page load times, particularly in high-latency or lossy network conditions.

To address these limitations, the developer community started exploring alternative transport protocols.

This led to the rise of QUICK (Quick UDP Internet Connections), a new protocol developed by Google.

Key advantages of QUIC are as follows:

Reduced latency: QUIC’s zero-round-trip connection establishment allows for faster initial page loads and improved responsiveness.

Multiplexing: Similar to HTTP2, QUIC enables multiple requests to be sent concurrently over a single connection, eliminating head-of-line blocking.

Improved Security: QUIC supports encryption by default, ensuring the security of all data exchanged between the client and server.

The rise of QUIC paved the way for the development of HTTP3. By leveraging QUIC as the underlying transport protocol instead of TCP, HTTP3 aims to address the limitations of TCP.

Let’s understand how it works.

HTTP3 uses QUIC, which is built on top of UDP (User Datagram Protocol). UDP is a connectionless protocol, meaning it doesn't require a formal connection to be established before sending data. This allows QUIC to set up connections more quickly than TCP.

Here's a simplified explanation of how HTTP3 works:

Connection establishment: When a client wants to connect to a server using HTTP3, it starts a QUIC handshake. This process sets up the connection between the client and the server.

QUIC and TLS integration: QUIC integrates with TLS 1.3 for encryption and security. The TLS handshake is performed within the QUIC connection establishment process, reducing the overall latency.

Sending requests: Once the connection is established, the client sends HTTP requests to the server. These requests are small packets of data that are sent using the QUIC protocol, which in turn uses UDP.

Receiving responses: When the server receives and processes the client's request, it sends back a response. The response is divided into smaller data packets and sent to the client using QUIC.

Faster connection setup: If the client and server have communicated before, QUIC can secure the connection in just one round trip or even zero round trips (0-RTT). In a 0-RTT case, the client sends a request to the server, and the server processes it immediately without needing a full handshake. This reduces the time it takes to establish a connection.

Handling packet loss: If a packet gets lost during the transfer, QUIC can detect it quickly without waiting for a timeout, unlike TCP. This means temporary network issues don't slow down the connection as much.

Parallel data streams: HTTP3 can send multiple streams of data simultaneously over the same connection. For example, when loading a website with images and scripts, the browser can load them all at once, making the website load faster.

Connection state: QUIC tracks the connection state throughout the process. This state is like a record of the ongoing conversation between the client and the server. It includes information about the connection status, congestion control, encryption keys, and security. By maintaining this state, QUIC ensures that conversations don't repeat and that the connection remains secure.

Closing the connection: When the client and server have finished exchanging requests and responses, either one of them can close the connection, which is also handled by the QUIC protocol.

The diagram below shows the difference between HTTPS over TCP & TLS and HTTPS over QUIC.

Now that we have explored the intricacies of HTTP1, HTTP2, and HTTP3, it’s important to compare these protocols side-by-side to understand their performance characteristics and suitability for different use cases.

The table below provides a comparison.

But what about the adoption?

Here are a few details about it:

Despite being the oldest of the three versions, HTTP1 (the 1.1 version, to be precise) is still widely used across the internet. Many legacy systems and older websites continue to rely on HTTP1 due to its simplicity and compatibility with a wide range of clients and servers.

Since its introduction in 2015, HTTP2 has seen significant adoption across the web. Major browsers, including Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Apple Safari, and Microsoft Edge, have implemented support for HTTP2. According to an estimate by HTTP Archive, over 60% of the web requests are served over HTTP2

As the newest member of the HTTP family, HTTP 3 is still in the early stage of adoption. However, it has been gaining traction since its standardization in 2022. Major tech companies like Google and Cloudflare have been at the forefront of implementing and promoting HTTP3.

In this post, we’ve witnessed the evolution of HTTP, from the simple beginning of HTTP1 to the performance-enhancing features of HTTP2 and the new potential of HTTP3 with its QUIC foundation.

Each version has built upon the lessons learned from its predecessors, addressing limitations and introducing new capabilities to meet the ever-growing demands of the modern web.

However, the adoption of new protocols is not without challenges.

One needs to carefully consider client and server compatibility as well as the readiness of your infrastructure and development tools. As software engineers, it’s also crucial to stay at the forefront of these developments and embrace the benefits offered by newer HTTP protocols wherever possible.