Developing an API involves a lot of work, from planning to implementation. It's crucial to have a clear and easy-to-understand versioning strategy to avoid confusing developers. In this week's issue, we'll explore different versioning strategies for APIs.

We'll begin by examining the reasons for versioning APIs and when it's necessary to release a new version. We'll also investigate various versioning strategies, how to label API versions, and methods for gracefully retiring outdated API versions.

So, without further ado, let’s jump right into it.

As we add new features to our API, fix existing issues, or change how our API works, we need to deliver these changes without disrupting our users. Let’s understand this with an example.

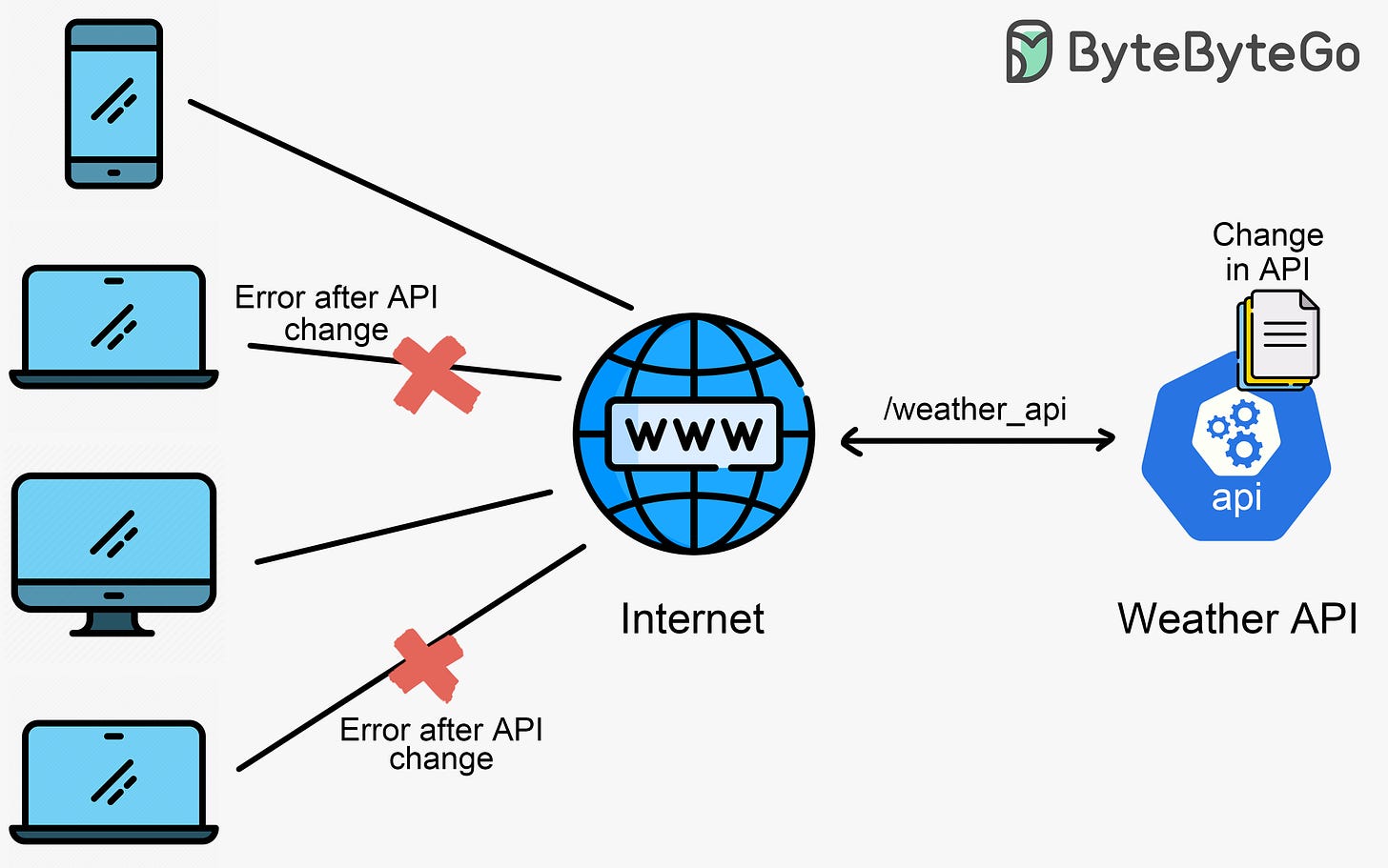

Imagine we have an API for weather forecasts. Thousands of websites use it to build dashboards and other applications.

Let's say we want to change the data contract of our response object. This could involve renaming a field, adding a new one, or changing the entire data contract. If we change an existing field name, our users’ applications might stop working or start throwing errors.

To fix this, we'd have to ask all our users to update their applications to work with our newest changes. If this happens often, our users will be frustrated.

Versioning solves this problem. When we want to release a breaking change, we upgrade the version of our API. We release it in a way that lets users choose when to accept the changes.

Once clients start using our API, they rely on it to work as originally designed. If we make changes or release new versions without considering our clients' needs, it could cause problems. That's why it's important to version our API and give clients the choice to upgrade when they're ready.

That's why designing for change is essential for APIs. We should use versioning to deliver changes to our users in a clear, consistent, and well-documented manner.

Versioning should not happen too often, as it can be disruptive and may require developers to update their code frequently.

Here are some scenarios when a new API version is necessary:

Breaking changes: When we make changes that could potentially break the software. For example, introducing new required fields in the payload or removing parameters that are no longer valid in an API call.

New Features: When adding new features or functionalities to the API while ensuring backward compatibility with existing users.

Bug Fixes: When addressing bugs or issues in the API, it's important to apply fixes without causing disruptions to existing consumers.

Performance Improvements: When implementing performance enhancements or optimizations that could change how users interact with our API.

So far, we've discussed API versioning and why we need it. Now, let's explore some approaches for versioning.

Additive change strategy

Explicit version strategy

In this approach, we add new features or fields to our API without modifying existing ones. Any updates to our API must be compatible with previous versions.

However, some operations are not allowed in an additive-change strategy. The table below shows some of those operations.

On the other hand, there are a few things we are allowed to do.

The last point in the allowed operations table might seem contradictory, but it's not. The main idea is to avoid breaking changes. As long as users can opt-in, we aren't breaking existing code.

For example, let's say that we have the following response in our fictitious weather API as shown below.

When we first released the API, we thought it was a good idea to include the pressure data. However, after several complaints from users that they don't always need the pressure data and it's just adding to the network load, we have decided to remove it.

With the additive change strategy, we can't simply remove the pressure data, as some clients might still use it.

However, we can remove it if users opt in to this change by adding a query parameter, like “exclude_pressure=true”, to indicate they want to use the newest API that excludes pressure data. This way, we solve the problem for those who have issues without breaking it for others.

Note: In an additive change strategy, adding new changes is not considered a breaking change. However, there are exceptions to this rule. For example, we can't add a required query parameter. In our example above, we can't make the “exclude_pressure=true” query parameter mandatory.

In this approach, we keep multiple versions of our API. When we want to make a change to our API, we release it as a new version. This is different from the additive change strategy, which doesn't allow breaking changes. The explicit-versioning strategy lets us make any kind of change, and that's the main difference.

This strategy requires us to create a numbered system that lets users interact with specific versions. We call this the versioning scheme. To support this access pattern, we have different methods to let consumers tell us which API version they want to use.

We discuss some of these methods below.

In this method, the version scheme is added as a base for the URI. The image below shows an example. The version scheme comes right before the widget’s resource. In some cases, we can put it after the resource, but only when we want to apply it to a particular resource or API method.

If we want to use the version scheme for a whole suite of API methods, it’s best to put it before the resource.

One benefit of this method is that it makes it easier to debug and inspect requests and their versions. The version is clearly shown in the request URI. On the flip side, we should avoid this approach if we don't support these endpoints as permanent links. Also, when using this approach, be prepared to support 300-level HTTP status codes. These codes indicate redirection for resources that have moved or are moving.

We can specify versions using HTTP headers, either by creating custom headers or using the “accept” content type header. Instead of putting the version scheme in the URI, we use headers, as shown in the example below.

One advantage of this approach is that it keeps our URIs clean and reduces clutter. However, it makes debugging harder because the version is less visible. It can also cause issues with client caching if the client thinks that two requests sent to different versions are the same request.

In this method, users can specify the version they want through request parameters. Using the same example as before, we add the version to the request parameters, as shown below.

This approach has benefits similar to URI components versioning. However, managing request parameters can be tricky in an application. The request parameters are only resolved after the request reaches a specific endpoint. This means that a single endpoint may need to handle a lot of requests and complex logic, based on the number of versions supported for that particular endpoint.

Now let's discuss a system for labeling API versions. A commonly used system is called the Semantic Versioning Specification, or SemVer for short.

In SemVer, there are three types of versions:

Major

Minor

Patch

Let's say there's a version 2.0.0 for an API.

We use major versions for breaking changes or backward-incompatible changes. If we make any of these changes, we increase the major version number. This would change the API version from 2.0.0 to 3.0.0.

Minor versions are for adding new features and functionality that are backward compatible. This type of change would result in the version going from 3.0.0 to 3.1.0.

Patch versions are for backward-compatible bug fixes. A patch version change would increase the version from 3.1.0 to 3.1.1.

As we continue to make changes and release new versions, we will have to maintain all the versions in our code base. However, this is not ideal in the long term. We have to consider how we can deprecate older versions.

Some organizations only maintain the two most recent versions behind the current one. For instance, if we are currently at version three and releasing version four of an API, we will work on deprecating version one leading up to that release.

It's best for us to maintain as few versions as possible to make maintenance easier.

We can also use a Sunset header. This header is added to the response object and indicates that the resource is expected to become unavailable at a specific time. Consumers should treat these sunset timestamps as hints. Once the sunset time is reached, requesting that resource should result in either 400-level errors or 300-level redirections. The sunset header doesn't need to specify which type of error will occur once the resource is decommissioned.

Let's turn our attention to a critical piece of the API versioning process: communication.

How can we make sure our developers know about new versions and have a transition period to switch versions?

Creating a new API version and immediately requiring all developers to use it would be a recipe for disaster. The only exception might be if our developer community consists entirely of internal developers or a small group of trusted partners who are familiar with our company’s version release process.

In most cases, we want to have a transition period during which older versions remain active and in use for some time. But how long should this period be? The general rule is anywhere from 6 to 12 months. During this time, we'll need to continue maintaining these older versions for things like security patches or bug fixes.

Here are some factors to consider when setting the deprecation date:

Managing API versions by hand can quickly become complicated and prone to errors, especially as APIs grow and evolve over time. This is where tools and libraries designed specifically for API versioning come into play.

Below, we list some of the popular API versioning tools in the market.

Additive strategies might work for smaller projects with limited capacity for change, but they probably won't work for enterprise applications or applications that are meant to evolve, grow, and add new business logic over time. An explicit versioning strategy is much more appropriate for managing complex changes. This is why companies like Stripe and Slack use an explicit versioning strategy – their products are constantly evolving, and an approach like the additive-change strategy simply isn’t feasible for them.

It’s important to wrap up this topic by emphasizing the importance of consistency in API versioning. Remember, developers widely use the best API in ways that were not originally anticipated. This means the company, not individual departments within the company, needs to set the versioning standard. Consistency will make it easier for developers to use and maintain their software using our APIs.