In our newsletter, we’ve mainly focused on system designs. This time, we’re switching gears to a topic just as crucial: the code itself. Ever encountered a system that looks great in design but turns out to be a headache in code? That’s our focus in this issue. We’re breaking down what makes code good versus bad. It’s all about turning those great designs into equally great code. Let’s dive into the details that truly make a difference in coding.

So, why should we care about good code? Think of it as the foundation of your software. Good code isn’t just about making things work; it’s about making them work efficiently and sustainably. It’s the difference between a smooth, efficient development experience and a frustrating, time-consuming one.

Good code maintains stability and predictability, even as your project grows in complexity. It’s like having a reliable tool that keeps performing, no matter how tough the job gets. When it comes to scaling up, good code is essential. It allows for expansion without the bottlenecks and headaches that come with a more shortsighted approach.

Sure, crafting good code requires more thought and effort at the outset. But this investment pays off by saving costs in the long run. Bad code, on the other hand, is a ticking time bomb - difficult to update and can lead to costly rewrites.

There’s also the aspect of teamwork and continuity. High-quality code, which is usually well-documented and adheres to standards, makes it easier for teams to collaborate. It streamlines the onboarding process, accelerates delivery, and facilitates team expansion.

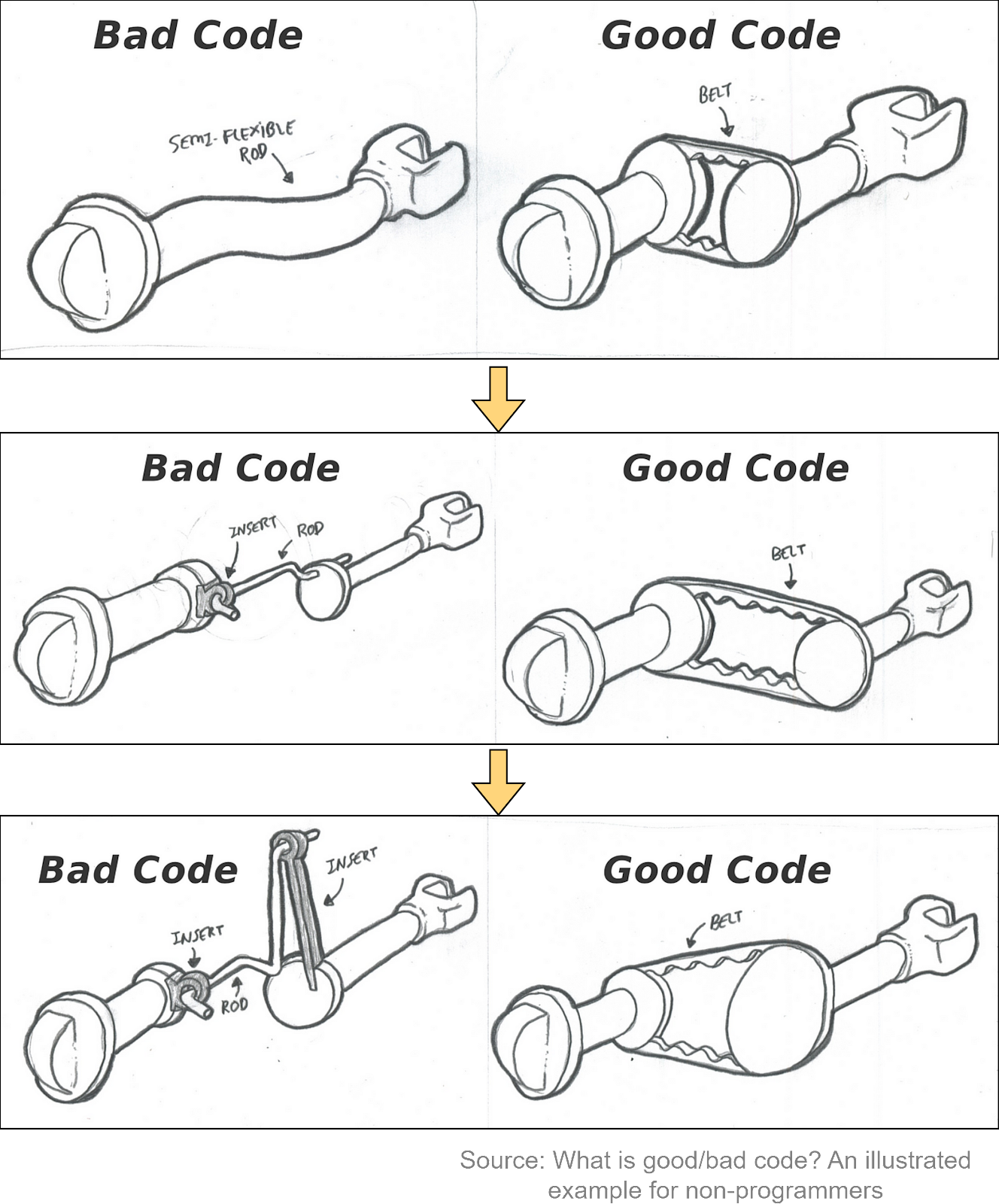

Let’s illustrate our points in the diagram below by comparing the two designs of a hypothetical knob-turning mechanism. The ‘good code’ uses a belt mechanism – flexible and easy to adjust. The ‘bad code’ version, however, relies on a rigid rod – more limited and prone to complications when changes are needed.

As requirements change and the knob needs to be relocated, the ‘good code’ with its belt mechanism easily accommodates this with a simple extension. The ‘bad code’, with its rigid rod, would require a whole new configuration, which is neither time nor cost-effective.

In another inevitable revision, we need to alter the speed at which the know turns. The ‘good code’ can simply switch to a different-sized gear. The ‘bad code’ setup, however, becomes increasingly complex as it requires additional parts and makes the system more convoluted and susceptible to breakage.

We're not advocating for overengineering from the get-go, especially in a startup context where resources are limited and the future is uncertain. The key is understanding the long-term implications of our coding choices. Building overly complex systems prematurely can be as counterproductive as repeatedly choosing quick fixes. The art lies in striking the right balance, a taste and skill that comes with experience and thoughtful consideration.

To kick things off, we’ve selected five broad areas for discussion. They're not exhaustive by any means, but they are good for a good starting point for a broader conversation on what takes code from bad to good. Are you ready to dive in?

Coding standards often start with naming conventions for classes, functions, variables, and more. This might seem simple, but it requires thoughtful design.

Consider the following service class names:

OrderManagementService

PaymentManagementService

DatabaseManagementServiceBy suffixing “ManagementService” to everything, the names become unnecessarily long and repetitive.

Next look at this function:

boolean processPayment(PaymentInstruction paymentInstruction) { Channel preferredChannel = paymentInstruction.getChannel(); channelFactory.getChannel(preferredChannel)

.send(paymentInstruction);

}Despite following naming conventions, “processPayment” does not communicate what exactly happens. The word “process” is too generic. It doesn’t tell us the current state of the payment and what we are going to do with it.

We understand from reading the code that it sends the payment instruction to an external channel for processing. We could name it “sendPaymentToExternalChannel()” but that exposes too many details. “startPayment()” can be a good choice, as it indicates initiating the payment flow without exposing internal details.

Good names like this reduce the need for excessive comments when collaborating!

Let’s look at another example.

String userId = paymentInstruction.getUserId();It would be good if “userId” were renamed to a more domain-relevant name, such as “payerId”.

String payerId = paymentInstruction.getPayerId();So in conclusion, effective names should:

Concisely and accurately describe purpose

Use business domain terminology

Avoid exposing implementation details

Sometimes urgent business requirements arise, but modifying existing code is too risky because it is badly-encapsulated with very few tests. In these situations, it is tempting to simply copy portions of code into new components as a shortcut, then start modifying to suit new needs.

We faced this circumstance when building a compliance-centric Know Your Client (KYC) service. It required user management functionality already present in a tightly coupled UserService module used elsewhere. Lacking time to modularize UserService, we copied relevant parts into the new KYC service and customized it.

So two duplicated versions of the user service logic stayed there long-term. Whenever we needed to update the user-related functionalities, we had to remember to modify two places - both the original UserService and the copied code now in the KYC service. This was often forgotten by developers, resulting in inconsistent behavior and outages. Keeping duplicate copies of the same logic in sync proved error-prone

This violates the key "Don't Repeat Yourself" (DRY) principle of software development:

While static analyzers help identify code duplication issues, it is important for developers to proactively design well-abstracted components from the start to avoid creating technical debt. Allocating time upfront to refactor modules like UserService into reusable core libraries with extension points could help.

We’ve all faced intense pressures to take clumsy shortcuts under deadline constraints. Yet whether addressed late or early, technical debt still accrues interest over time. We should leverage any influence we have to gently guide stakeholders towards more sustainable thinking, even in small steps.

We have all seen code like this:

PaymentInstruction createPaymentInstruction(String payerId,

String receiverId,

String orderId,

Channel preferredChannel,

String callbackUrl,

Currency currency,

Amount amount) {

// create payment instruction

}With 7 parameters, this grows unwieldy over time. We can encapsulate the parameters into a single object:

public class PaymentInstructionParameters {

private String payerId;

private String receiverId;

private String orderId;

private Channel preferredChannel;

private String callbackUrl;

private Currency currency;

private Amount amount;

}

PaymentInstruction createPaymentInstruction(

final PaymentInstructionParameters params) {

// create payment instruction

} This is better, but string parameters are still error-prone. We could mistakenly swap IDs. Using builder pattern improves this:

public class PaymentInstructionParameters {

private String payerId;

private String receiverId;

private String orderId;

private Channel preferredChannel;

private String callbackUrl;

private Currency currency;

private Amount amount;

public PaymentInstruction newPaymentInstruction() {

return PaymentInstruction.builder()

.payerId(payerId)

.receiverId(receiverId)

.orderId(orderId)

.preferredChannel(preferredChannel)

.callbackUrl(callbackUrl)

.currency(currency)

.amount(amount);

}

}Now each parameter is explicitly set in a self-contained builder class. This reduces complexity and mistakes for consumers.

Encapsulating messy parameters into well-defined objects with targeted factories/builders improves understandability and reliability.

Too many nested “if-else” statements are considered bad smell in coding. The diagram below shows an example. While logic may start simple, developers over time keep adding new conditional branches. Before long, it looks like this

if(condition) {

//Nested if else inside the body of “if”

if(condition2) {

//Statements inside the body of nested “if”

}

else {

//Statement inside the body of nested “else”

}

}

else {

//Statement inside the body of “else”

}There are guidelines to improve readability of conditional logic:

Return early from functions when conditions fail instead of nesting.

Encapsulate complex condition checking into description functions or methods.For example, Google Guava provides Preconditions utility class.

public static double sqrt(double value) {

Preconditions.checkArgument(value >= 0.0, "negative value: %s", value);

// calculate the square root

}The goal is to flatten nested logic by distributing checks and extracting blocks into cohesive units with clear responsibilities. This improves readability and maintainability over time as new requirements arise.

If we use a modern IDE, it generates getters and setters for a class by default. While convenient, this enables modifying data whenever we want, which can lead to bugs from seemingly small changes. Martin Fowler includes mutable data as one of the code smells in Refactoring.

In functional programming, an object's state cannot change after creation. To update values, we copy them into a new object (deep copy). Immutable data structures allow parallelism by letting multiple processes access and manipulate data without risk of conflicts.

In object-oriented code, there are tricks to avoid accidental data changes:

Remove setters. For example, when receiving a callback from an external payment channel, update state through an API instead of directly modifying values.

class PaymentInstruction {

PaymentInstruction complete(CallBackResult result) {

return new PaymentInstruction(..., result.getCode(), ...);

}

}Use event sourcing. In this programming paradigm, events are immutable and can be stored in an append-only event store. Events are first-class citizens. To change an object’s state, we generate a new immutable event. It works like this:

class EventHandler {

void onNewEvent(NewPaymentEvent newPaymentEvent) {

createPayment(newPaymentEvent);

}

void onUpdateEvent(UpdatePaymentEvent updatePaymentEvent) {

payment.apply(newPaymentEvent);

}

}Embracing immutable data can lead to more robust, maintainable, and parallelizable code. By incorporating strategies like removing setters and using event sourcing, object-oriented programming can also benefit from the advantages of immutability. While it may require a shift in mindset from traditional mutable practices, the resulting code quality and system reliability are often worth the effort.

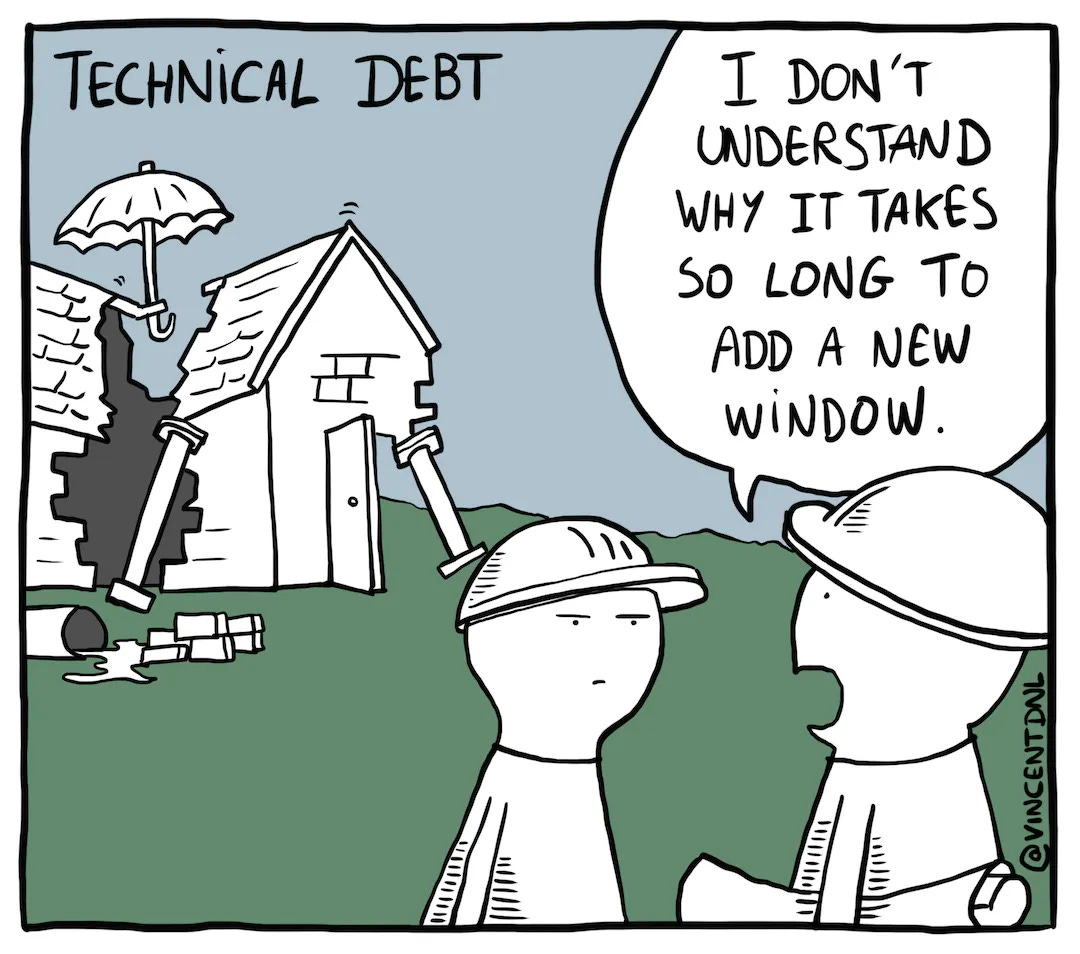

Bad code smells can accumulate as technical debt over time. Like financial debt, technical debt enables short-term gains but requires eventual repayment. Effectively managing technical debt is essential.

There is no eliminating debt completely in software projects. We should embrace it and properly manage it.

Quantify debt: Tools like SonarQube integrate metrics highlighting technical debt in terms of effort to resolve. Tracking debt prevents uncontrolled accumulation in code.

Strategically leverage debt when urgency demands it: “Quick and dirty” solutions enable moving fast to capture business opportunities. Technical debt can provide leverage to quickly establish market dominance early on.

Allocate resources to pay down debt: Schedule refactoring work each sprint or host “tech debt weeks” every few months. This prevents letting debt linger too long.

Convey the urgency to management: Get leadership on board with "repairing the roof on a sunny day" before disaster strikes. The diagram below shows a worst-case scenario of unmanaged debt, where key stakeholders are unaware until too late.

We discussed some common code smells and their recommended refactoring solutions. In the long run, high-quality code reduces maintenance costs and improves system stability and maintainability.

We also discussed the reality of technical debt accumulating through quick-win development shortcuts. Like financial debt, managed technical debt can strategically accelerate short-term deliveries. However, we need to allocate time to repay the debt before it is too late.