In the fast-paced world of software development, writing robust, maintainable, and scalable code is critically important. One way to achieve this is by following a set of fundamental design principles known as the SOLID principles. These principles provide a clear framework for crafting software that is easy to understand, extend, and maintain.

In this newsletter, we will explore the SOLID principles, examining each component in detail. We will review practical implementation guidance and best practices for applying them.

Now, let's begin our exploration with a brief overview of the SOLID principles first.

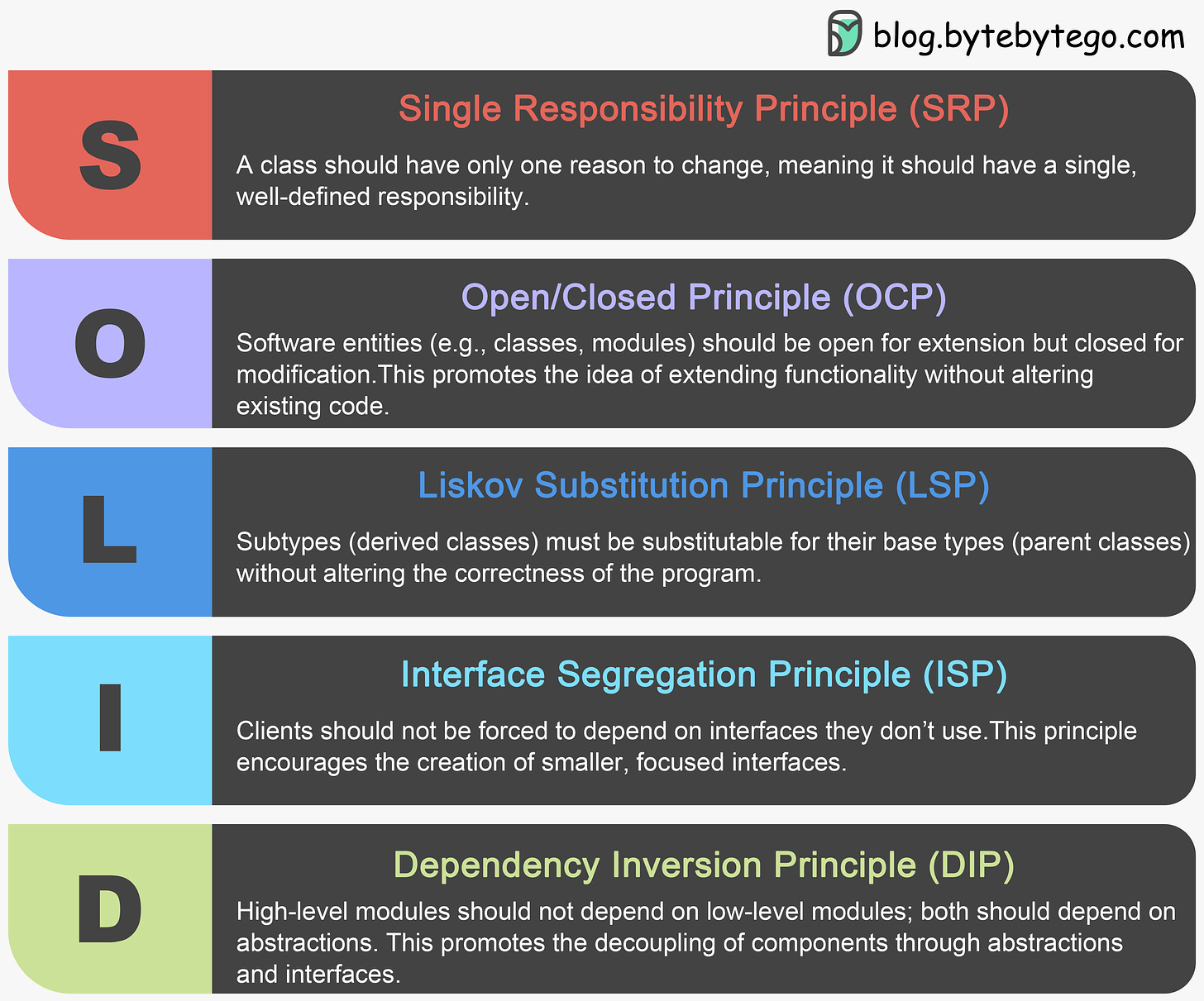

The SOLID principles are a set of five fundamental design principles that were introduced by Robert C. Martin to guide software developers in creating maintainable, scalable, and flexible software systems. These principles, when followed, contribute to the development of software that is easier to understand, modify, and extend over time.

The SOLID acronym stands for:

Design principles, such as the SOLID principles, play a pivotal role in the software development process for several reasons:

Maintainability: Following sound design principles makes code more maintainable. When code is well-structured and adheres to these principles, it becomes easier to identify and fix issues, add new features, and make improvements without causing unintended consequences.

Scalability: Well-designed software is scalable. It can accommodate changes and growth in requirements without requiring extensive rework or becoming increasingly complex.

Code Reusability: Adhering to design principles often leads to code that is more reusable. Reusable components save time and effort in development and testing.

Collaboration: Design principles provide a common framework for developers to work within. This common understanding promotes collaboration and reduces misunderstandings among team members.

Reduced Bugs and Pitfalls: Following design principles helps to identify and mitigate common programming pitfalls and design flaws. This results in fewer bugs and more robust software.

Future-Proofing: Well-designed software can adapt to changing requirements and technologies. It's an investment in the long-term viability of the software product.

Now, let's deep dive into each component of the SOLID principles.

The “S” in the SOLID principles stands for the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP), which states that a class should have only one reason to change or, in other words, it should have a single, well-defined responsibility or job within a software system.

Let's take a look at a Java code example below that clearly violates the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) principle:

public class Employee {

private String name;

private double salary;

public void calculateSalary() {

// definition

}

public void generatePayrollReport() {

// definition

}

}In the above example, the Employee class has two responsibilities: calculating an employee's salary and generating a payroll report. This violates the SRP because it has more than one reason to change.

To address the violation of the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) in our previous example, let's refactor the code to separate concerns and ensure that each class has a single, well-defined responsibility. We'll create distinct classes for calculating an employee's salary and generating a payroll report:

public class Employee {

private String name;

private double salary;

public void calculateSalary() {

// definition

}

}

public class PayrollReportGenerator {

public void generatePayrollReport(Employee employee) {

// definition

}

}In the refactored solution, the responsibilities of calculating the salary and generating a payroll report have been separated into two distinct classes (Employee and PayrollReportGenerator), each with a single responsibility. This adheres to the SRP.

Let’s take a look at the visual representation of the classes and implementation of the single responsibility principle (SRP).

Navigating the application of the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) comes with common pitfalls and mistakes we should recognize. Understanding these challenges allow us to better avoid them and create more robust, maintainable code. Let's explore some of these potential issues:

It is a common mistake to overload classes with multiple responsibilities, as demonstrated in the initial example. This can lead to complex and difficult-to-maintain code.

Ignoring the principle of cohesion, which is related to SRP, can result in classes that perform unrelated tasks, making the code less organized and harder to manage.

To adhere to the Single Responsibility Principle effectively, consider the following guidelines:

Clearly define the responsibilities or roles that each class should have. Avoid mixing unrelated tasks within a single class.

Use the Separation of Concerns (SoC) principle to divide your application's functionality into distinct modules or classes, each responsible for a specific concern.

If you find a class with multiple responsibilities, refactor it into smaller, more focused classes, each with a single responsibility.

Design your classes in a way that changes to one responsibility do not affect the implementation of other responsibilities.

Conduct code reviews to ensure that classes adhere to SRP. Encourage team members to provide feedback on class responsibilities.

The Open/Closed Principle (OCP) states that software entities (such as classes, modules, and functions) should be open for extension but closed for modification. In other words, you should be able to add new functionality or behavior to a software entity without altering its existing source code.

To understand the Open/Closed Principle (OCP) better, let's take a look at a Java code example that clearly violates this principle:

public class Rectangle {

protected int width;

protected int height;

public Rectangle(int width, int height) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

public int getWidth() {

return width;

}

public void setWidth(int width) {

this.width = width;

}

public int getHeight() {

return height;

}

public void setHeight(int height) {

this.height = height;

}

public int calculateArea() {

return width * height;

}

}In the above example, the Rectangle class is designed to calculate the area of a rectangle. However, if you want to extend it to work with other shapes like circles or triangles, you would need to modify the class, violating the OCP.

We'll apply the OCP (Open-Closed Principle) and see how we can solve the issue mentioned above:

public abstract class Shape {

public abstract int calculateArea();

}

public class Rectangle extends Shape {

private int width;

private int height;

public Rectangle(int width, int height) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

@Override

public int calculateArea() {

return width * height;

}

}

public class Circle extends Shape {

private int radius;

public Circle(int radius) {

this.radius = radius;

}

@Override

public int calculateArea() {

return (int) (Math.PI * radius * radius);

}

}In this refactored solution, the Shape class is introduced as an abstract base class for all shapes. Each specific shape (Rectangle, Circle) extends the Shape class and provides its implementation of the calculateArea method. This adheres to the OCP because you can add new shapes without modifying existing code.

Below is the visual representation of the classes and implementation of OCP.

Let's examine some of the common pitfalls and mistakes that developers may encounter:

A common mistake is directly modifying existing code to add new functionality instead of extending it. This violates the OCP and can introduce bugs or regressions.

Failing to introduce appropriate abstractions or base classes can lead to code that is hard to extend without modification.

To implement the Open/Closed Principle effectively, consider the following guidelines:

Introduce abstract classes or interfaces to create abstractions that software entities can extend or implement to provide new functionality.

When extending an abstract class or implementing an interface, override methods to provide specific behavior for each entity.

Use polymorphism to treat objects of different concrete classes (e.g., different shapes) uniformly through their common base class or interface.

Use dependency injection to inject dependencies or behaviors into classes rather than hardcoding them, making it easier to extend functionality.

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) states that objects of a derived class (subtype) should be able to replace objects of the base class (supertype) without affecting the correctness of the program. In other words, if class A is a subtype of class B, then instances of class B should be replaceable with instances of class A without causing issues.

To understand the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) better, let's take a look at a Java code example that clearly violates this principle:

class Bird {

void fly() {

System.out.println("A bird can fly.");

}

}

class Ostrich extends Bird {

@Override

void fly() {

// Ostriches cannot fly, so this method is overridden to do nothing.

}

}In this example, the Ostrich class is a subtype of the Bird class. However, it violates the LSP because it overrides the fly method which is not related to Ostrich. This means that an instance of Ostrich cannot be substituted for an instance of Bird without causing unexpected behavior.

We'll apply the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) and see how we can solve the issue mentioned above:

class Bird {

void move() {

System.out.println("A bird can move.");

}

}

class Ostrich extends Bird {

@Override

void move() {

System.out.println("An Ostrich can move.");

}

}In this revised example, the Ostrich class is a subtype of the Bird class, and it overrides the move method to provide a meaningful behavior that aligns with the LSP. An instance of Ostrich can be substituted for an instance of Bird without causing issues.

Here is the visual representation of the classes and implementation of LSP.

As we learn how to apply the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP), it's essential to be aware of common pitfalls and mistakes that developers may encounter. Let's explore some of these potential issues:

A common mistake is overriding methods in derived classes in a way that contradicts the behavior of the base class.

Changing the preconditions (input requirements) or postconditions (output guarantees) of methods in derived classes can violate LSP.

To implement the Liskov Substitution Principle effectively, consider the following guidelines:

Ensure that derived classes maintain the behavioral compatibility of their base classes. Methods in derived classes should follow the same contracts as the base class methods.

If a base class method has specific preconditions (e.g., input constraints), derived class methods should have the same or weaker preconditions. Postconditions (output guarantees) should be as strong as or stronger than those of the base class methods.

Use polymorphism to enable the substitution of derived class objects for base class objects. This often involves overriding methods to provide specialized behavior while maintaining the core functionality.

The “I” in the SOLID acronym stands for the Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) which emphasizes that clients (classes or components that use interfaces) should not be forced to depend on interfaces they don't use. In other words, an interface should have a specific and focused set of methods that are relevant to the implementing classes.

Let's check out a Java code example that clearly violates this principle:

// Monolithic interface

interface Worker {

void work();

void eat();

void sleep();

}In this example, the Worker interface contains three methods: work(), eat(), and sleep(). However, not all classes that implement this interface may need all these methods. This can lead to classes being forced to implement methods that are irrelevant to their functionality, violating the ISP.

We'll apply the Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) and see how we can solve the issue mentioned above:

interface Workable {

void work();

}

interface Eatable {

void eat();

}

interface Sleepable {

void sleep();

}In this refactored solution, the Worker interface has been split into three smaller, more focused interfaces: Workable, Eatable, and Sleepable. Now, classes can choose to implement only the interfaces that are relevant to their functionality, adhering to the ISP.

A visual representation of the refactored interfaces (Workable, Eatable, Sleepable) adhering the ISP is shown below.

Let's examine some of the common pitfalls and mistakes that developers may encounter while applying ISP:

Creating large, monolithic interfaces with too many methods can lead to classes implementing methods they don't need, violating ISP.

Modifying an interface to add or remove methods can break existing implementations. It's important to consider the impact on clients when making changes.

To adhere to the Interface Segregation Principle effectively, consider the following guidelines:

Design interfaces with a specific purpose, containing only methods that are directly related to that purpose.

Prefer having multiple smaller interfaces that clients can choose to implement rather than a single large interface with everything.

Think from the perspective of the clients (classes that implement the interface) and provide them with interfaces that are tailored to their needs.

If you need to add new methods to an existing interface without breaking existing implementations, consider using default methods, which provide default implementations for new methods.

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) states that high-level modules (or classes) should not depend on low-level modules; both should depend on abstractions (interfaces or abstract classes). In simpler terms, the principle encourages the use of abstract interfaces to decouple higher-level components from lower-level details.

To understand the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) better, let's take a look at a Java code example that clearly violates this principle:

class LightBulb {

void turnOn() {

// Code to turn on the light bulb.

}

}

class Switch {

private LightBulb bulb;

Switch(LightBulb bulb) {

this.bulb = bulb;

}

void operate() {

bulb.turnOn();

}

}In this example, the Switch class directly depends on the LightBulb class, which is a lower-level detail. This is a violation of the DIP because high-level modules like Switch should not depend on low-level details.

We'll apply the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) and see how we can solve the issue mentioned above:

interface Switchable {

void turnOn();

}

class LightBulb implements Switchable {

@Override

public void turnOn() {

// Code to turn on the light bulb.

}

}

class Switch {

private Switchable device;

Switch(Switchable device) {

this.device = device;

}

void operate() {

device.turnOn();

}

}In this refactored solution, the Switch class depends on the Switchable interface, which is an abstraction. The LightBulb class implements the Switchable interface. This adheres to the DIP because high-level modules now depend on abstractions rather than low-level details.

A visual representation of the dependency inversion, showing how high-level modules (Switch) depend on abstractions (Switchable) rather than concrete implementations (LightBulb) is shown below.

Let’s examine some of the pitfalls and common mistakes as we learn to apply the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP):

A common mistake is having high-level modules directly depend on low-level details, violating the DIP.

Creating weak or poorly defined abstractions can make it challenging to adhere to the DIP effectively.

To implement the Dependency Inversion Principle effectively, consider the following guidelines:

Introduce abstract interfaces or abstract classes to represent dependencies, allowing high-level modules to depend on these abstractions.

Use dependency injection to inject concrete implementations into high-level modules through their abstractions. This promotes loose coupling.

Combining DIP with other SOLID principles can lead to cleaner and more maintainable code.

Consider using dependency injection frameworks like Spring or Guice to manage dependencies automatically.

The SOLID principles are essential guidelines for designing and maintaining high-quality, flexible, and robust software systems. Encouraging the application of these principles in software development practices can lead to more efficient development, fewer bugs, and a smoother evolution of software products over time. Embracing SOLID principles is an investment in the long-term success and sustainability of software projects.

‘Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship’ by Robert C. Martin

‘Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software’ by Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John Vlissides.