In the last issue, we discussed the benefits of using a message queue. Then we went through the history of message queue products. It seems that nowadays Kafka is the go-to product when we need to use a message queue in a project. However, it's not always the best choice when we consider specific requirements.

Let’s use our Starbucks example again. The two most important requirements are:

Asynchronous processing so the cashier can take the next order without waiting.

Persistence so customers’ orders are not missed if there is a problem.

Message ordering doesn’t matter much here because the coffee makers often make batches of the same drink. Scalability is not as important either since queues are restricted to each Starbucks location.

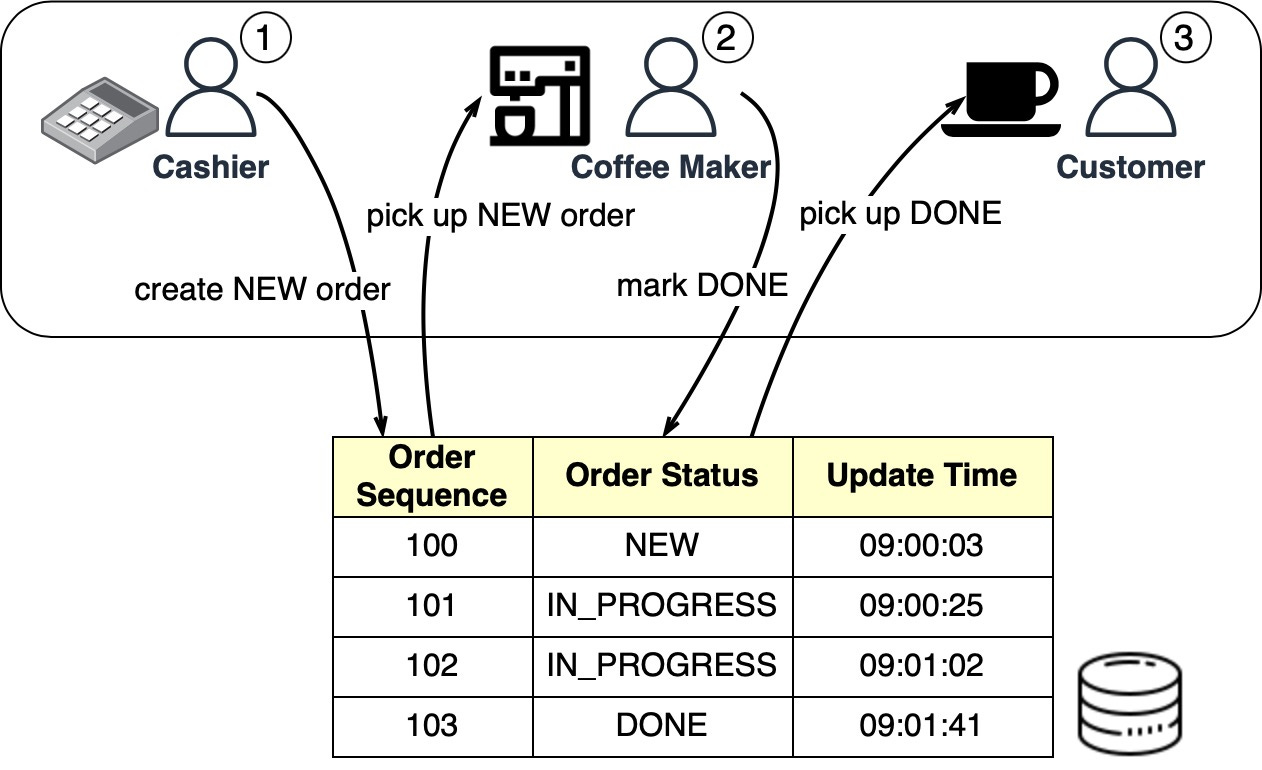

The Starbucks queues can be implemented in a database table. The diagram below shows how it works:

When the cashier takes an order, a new order is created in the database-backed queue. The cashier can then take another order while the coffee maker picks up new orders in batches. Once an order is complete, the coffee maker marks it done in the database. The customer then picks up their coffee at the counter.

A housekeeping job can run at the end of each day to delete complete orders (that is, those with the “DONE status).

For Starbucks’ use case, a simple database queue meets the requirements without needing Kafka. An order table with CRUD (Create-Read-Update-Delete) operations works fine.

A database-backed message queue still requires development work to create the queue table and read/write from it. For a small startup on a budget that already uses Redis for caching, Redis can also serve as the message queue.

There are 3 ways to use Redis as a message queue:

Pub/Sub

List

Stream

The diagram below shows how they work.

Pub/Sub is convenient but has some delivery restrictions. The consumer subscribes to a key and receives the data when a producer publishes data to the same key. The restriction is that the data is delivered at most once. If a consumer was down and didn’t receive the published data, that data is lost. Also, the data is not persisted on disk. If Redis goes down, all Pub/Sub data is lost. Pub/Sub is suitable for metrics monitoring where some data loss is acceptable.

The List data structure in Redis can construct a FIFO (First-In-First-Out) queue. The consumer uses BLPOP to wait for messages in blocking mode, so a timeout should be applied. Consumers waiting on the same List form a consumer group where each message is consumed by only one consumer. As a Redis data structure, List can be persisted to disk.

Stream solves the restrictions of the above two methods. Consumers choose where to read messages from - “$” for new messages, “<id>” for a specific message id, or “0-0” for reading from the start.

In summary, database-backed and Redis-backed message queues are easy to maintain. If they can't satisfy our needs, dedicated message queue products are better. We'll compare two popular options next.

For large companies that need reliable, scalable, and maintainable systems, evaluate message queue products on the following:

Functionality

Performance

Scalability

Ecosystem

The diagram below compares two typical message queue products: RabbitMQ and Kafka.

RabbitMQ works like a messaging middleware - it pushes messages to consumers then deletes them upon acknowledgment. This avoids message pileups which RabbitMQ sees as problematic.

Kafka was originally built for massive log processing. It retains messages until expiration and lets consumers pull messages at their own pace.

RabbitMQ is written in Erlang which makes modifying the core code challenging. However, it offers very rich client API and library support.

Kafka uses Scala and Java but also has client libraries and APIs for popular languages like Python, Ruby, and Node.js.

RabbitMQ handles tens of thousands of messages per second. Even on better hardware, throughput doesn’t go much higher.

Kafka can handle millions of messages per second with high scalability.

Many modern big data and streaming applications integrate Kafka by default. This makes it a natural fit for these use cases.

Now that we’ve covered the features of different message queues, let’s look at some examples of how to choose the right product.

For an eCommerce site with services like shopping cart, orders, and payments, we need to analyze logs to investigate customer orders.

The diagram below shows a typical architecture uses the “ELK” stack:

ElasticSearch - indexes logs for full-text search

LogStash - log collection agent

Kibana - UI for search and visualizing logs

Kafka - distributed message queue

This architecture works well for large eCommerce sites with many service instances.

Kafka efficiently collects log streams from each instance. ElasticSearch consumes the logs from Kafka and indexes them. Kibana provides a search and visualization UI on top of ElasticSearch.

Kafka handles high volume log collection, ElasticSearch indexes the logs for fast text search, and Kibana enables users to visually analyze orders, users, products, etc.

Ecommerce sites like Amazon use past behaviors and similar users to calculate product recommendations.

The diagram below shows how it works:

User clicks on product recommendations indicate satisfaction.

Clickstream data is captured by Kafka

Flink aggregates clickstream data

Aggregated data combines with product info and user relationships in a data lake

Data trains machine learning models to improve recommendations

So Kafka streams the raw clickstream data, Flink processes it, and model training consumes the aggregated data from data lake. This allows continuously improving the relevance of recommendations for each user.

Similar to the log analysis system, we need to collect system metrics for monitoring and troubleshooting. The difference is that metrics are structured data while logs are unstructured text.

Here is the architecture: metrics data is sent to Kafka and aggregated in Flink. The aggregated data is consumed by a real-time monitoring dashboard and alerting system (for example, PagerDuty).

We collect different levels of metrics.

Host level: CPU usage, memory usage, disk capacity, swap usage, I/O, network status

Process level: pid, threads, open file descriptors

Application level: throughput, latency, etc

This provides a complete view of the observables for the whole system.

Sometimes, in a distributed environment, we want to delay message delivery.

Kafka consumers pull messages immediately. It does not natively support delayed delivery.

RabbitMQ does support delaying messages by setting a special header in the message.

If Kafka is already in use but we need to delay some messages like email notifications, adding RabbitMQ may be overkill.

But if delays are heavily used, implementing a custom delay queue in Kafka is inefficient vs using RabbitMQ’s native delay feature. The choice depends on the existing tech stack and how prevalent delayed messages are in the architecture.

Change Data Capture (CDC) streams database changes to other systems for replication or cache/index updates.

CDC is usually modeled as an event stream. It works by observing database transaction logs and streaming changes to Kafka. Downstream systems like search, caches, and replicas are updated from Kafka.

For example, in the diagram below, the transaction log is sent to Kafka and ingested by ElasticSearch, Redis, and secondary databases.

This architecture keeps downstream systems updated and makes horizontal scalability easy. For example, to add a replica for heavy queries, take a snapshot then use a Kafka connector to stream changes.

CDC with Kafka is flexible - replicas stay in sync, search and cache refresh, and scaling out consumers is straightforward.

Upgrading legacy services is challenging - old languages, complex logic, lack of tests. Directly replacing these legacy services is risky. However, we can mitigate the risk by leveraging a messaging middleware.

For example, to upgrade the order service in the diagram below, we update the legacy order service to consume input from Kafka and write the result to ORDER topic. New order service consumes the same input and writes the result to ORDERNEW topic. A reconciliation service compares ORDER and ORDERNEW. If they are identical, the new service passes testing.

This validates the new service before direct replacement. The legacy and new service run in parallel, decoupled by Kafka topics. Once reconciled, the new service can safely replace the old.

Messaging enables low risk, decoupled migration of legacy systems.

In this issue, we covered several message queue implementation options:

A database-backed queue meets simple needs like the Starbucks example. Redis provides queue features through Pub/Sub, Lists, and Streams. For more complex systems, Kafka is a popular choice supported by many data streaming tools. However, factors like RabbitMQ’s native delay feature are worth considering.

We also walked through common use cases where message queues excel.

In summary, there are a few options for message queue implementations and products. The use case, existing infrastructure, and specific requirements determine the best choice. Kafka is common but not universal - consider alternatives like RabbitMQ when evaluating needs.