In this article, we are going to explore effective database indexing strategies. Database performance is critical to any large-scale, data-driven application. Poorly designed indexes and a lack of indexes are primary sources of database application bottlenecks. Designing efficient indexes is critical to achieving good database and application performance. As databases grow in size, finding efficient ways to retrieve and manipulate data becomes increasingly important. A well-designed indexing strategy is key to achieving this efficiency. This article provides an in-depth look at index architecture and discusses best practices to help us design effective indexes to meet the needs of our application.

Let's start with the basics of indexing in databases. An index, much like the index at the end of a book, is a data structure that speeds up data retrieval operations. Just as a book index lists keywords alongside page numbers to help locate information quickly, a database index serves a similar purpose, speeding up data retrieval without needing to scan every row in a database table.

The structure of a database index includes an ordered list of values, with each value connected to pointers leading to data pages where these values reside. Index pages hold this organized structure which provides a more efficient way to locate specific information.

Indexes are typically stored on disk. They are associated with a table to speed up data retrieval. Keys made from one or more columns in the table make up the index, which, for most relational databases, are stored in a B+ tree structure. This structure allows the database to locate associated rows efficiently.

Finding the right indexes for a database is a balancing act between quick query responses and update costs. Narrow indexes, or those with fewer columns, save on disk space and maintenance, while wide indexes cater to a broader range of queries. Often, it requires several iterations of designs to find the most efficient index.

In its simplest form, an index is a sorted table that allows for searches to be conducted in O(Log N) time complexity using binary search on a sorted data structure.

Various data structures, such as B-Trees, Bitmaps, or Hash Maps, can be used to implement indexes. Though all these structures offer efficient data access, their implementation details differ.

For relational databases, indexes are often implemented using a B+ Tree, which is a variant of B-Tree.

The B+ Tree is a specific type of tree data structure, and understanding it requires some background on its predecessor, the B-Tree.

The B-Tree, or Balanced Tree, is a self-balancing tree data structure that maintains sorted data and allows for efficient insertion, deletion, and search operations. All these operations can be performed in O(Log N) time.

Here’s what distinguishes the structure of a B-Tree:

All leaves are at the same level - this is what makes the tree 'balanced'.

All internal nodes (except for the root) have a number of children ranging from d (the minimum degree of the tree) to 2d. The root, however, has at least two children.

A non-leaf node with ‘k' children contains k-1 keys. This means if a node has three children (k=3), it will hold two keys (k-1) that segment the data into three parts corresponding to each child node.

The B-Tree is an excellent data structure for storing data that doesn't fit into the main memory because its design minimizes the number of disk accesses. And because the tree is balanced, with all leaf nodes at the same depth, lookup times remain consistent and predictable.

The B+ Tree is a variant of the B-Tree and is widely used in disk-based storage systems, especially for database indexes. The B+ Tree has certain unique characteristics that improve on the B-Tree.

In a B+ Tree, the data pointers (the pointers to the actual records) are stored only at the leaf nodes. The internal nodes only contain keys and pointers to other nodes. This means that many more keys can be stored in internal nodes, reducing the overall height of the tree. This decreases the number of disk accesses required for many operations.

All leaf nodes are linked together in a linked list. This makes range queries efficient. We can access the first node of the range and then simply follow the linked list to retrieve the rest.

In a B+ Tree, every key appears twice, once in the internal nodes and once in the leaf nodes. The key in the internal nodes acts as a division point for deciding which subtree the desired value could be in.

These features make B+ Trees particularly well-suited for systems with large amounts of data that won't fit into main memory. Since data can only be accessed from the leaf nodes, every lookup requires a path traversal from the root to a leaf. All data access operations take a consistent amount of time. This predictability makes B+ Trees an attractive choice for database indexing.

Now we understand how B+ Tree is used for indexing, let’s see how a typical database engine uses it to maintain indexes.

A clustered index reorders the way records in the table are physically stored. It does not store rows randomly or even in the order they were inserted. Instead, it organizes them to align with the order of the index, hence the term “clustered”. The specific column or columns used to arrange this order is referred to as the clustered key.

The arrangement determines the physical order of data on disk. Think of it as a phonebook, which is sorted by last name, then first name. The data which is phone number and address is stored along with the sorted index.

However, because the physical data rows can be sorted in only one order, a table can have only one clustered index. Adding or altering the clustered index can be time-consuming, as it requires physically reordering the rows of data.

It's also important to select the clustered key carefully. Typically, it's beneficial to choose a unique, sequential key to avoid duplicate entries and minimize page splits when inserting new data. This is why, in many databases, the primary key constraint automatically creates a clustered index on that column if no other clustered index is explicitly defined.

However, an exception to this general guidance is PostgreSQL. In PostgreSQL, data is stored in the order it was inserted, not based on the clustered index or any other index. However, PostgreSQL provides the CLUSTER command, which can be used to reorder the physical data in the table to match a specific index. It's important to note that this physical ordering is not automatically maintained when data is inserted or updated - to maintain the order, the CLUSTER command needs to be rerun.

Non-clustered indexes are a bit like the index found at the back of a book. They maintain a distinct list of key values, with each key having a pointer indicating the location of the row that contains that value. The pointers tie the index entries back to the data pages.

Since non-clustered indexes are stored separately from the data rows, the physical order of the data isn't the same as the logical order established by the index. This separation means that accessing data using a non-clustered index involves at least two disk reads, one to access the index and another to access the data. This is in contrast to a clustered index, where the index and data are one and the same.

A major advantage of non-clustered indexes is that we can have multiple non-clustered indexes on a table, each being useful for different types of queries. They are especially beneficial for queries involving columns not included in the clustered index. They enhance the performance of queries that don't involve the clustered key or don't require scanning a range of data.

It's important to consider the trade-off. While non-clustered indexes can speed up read operations, they can slow down write operations, as each index must be updated whenever data is modified in the table. It's crucial to strike a balance when deciding the number and type of non-clustered indexes for a given table.

Indexes speed up data retrieval by providing a more efficient path to the data without scanning every row. There are different types of indexes. We’ll take a look at the common ones.

The primary index of a database is typically the main means of accessing data. When creating a table, the primary key often doubles as a clustered index, which means that the data in the table is physically sorted on disk based on this key. This ensures quick data retrieval when searching by the primary key.

The efficiency of this setup largely depends on the nature of the primary key. If the key is sequential, writing to the table is generally efficient. But if the key isn't sequential, reshuffling of data might be needed to maintain the order. This can make the write process less efficient.

Note that while the primary key often serves as the clustered index, this is not a hard and fast rule. The clustered index could be based on any column or set of columns, not necessarily the primary key.

In certain scenarios, the primary key may not be sufficient for executing queries efficiently. For instance, queries that filter or sort data based on non-primary-key columns could benefit from additional indexes. In these cases, a secondary index is useful.

A secondary index is a sorted structure that references the records in the main table. Unlike the primary index, a secondary index is a non-clustered index. It maintains a separate list of key-value pairs, with each key having a pointer to the corresponding record in the main table.

While secondary indexes can speed up queries on non-primary-key columns, they may slow down write operations. This is because every time a write operation takes place, all indexes that include the affected data must be updated. In read-heavy applications, the benefits of faster query responses often outweigh the cost of slower writes. In these situations, having multiple secondary indexes is a preferable choice.

A composite index, also known as a multi-column index or a concatenated index, includes more than one column in the index key. This type of index is especially beneficial for queries that filter or sort by a specific set of columns.

For example, let's say we have a "Customers" table, and we often find ourselves running a query like SELECT * FROM Customers WHERE lastName = 'Smith' AND firstName = 'John'. Instead of creating two separate indexes on the "lastName" and "firstName" columns, we could create a single composite index on both columns.

One crucial detail to note about composite indexes is the order of the columns. The column order can significantly affect the index's usefulness. In the example above, the composite index would be beneficial for queries that involve both "lastName" and "firstName", and also for queries that only involve "lastName". However, it wouldn't be efficient for queries that only involve "firstName", as the index is ordered by "lastName" first.

Therefore, when creating a composite index, it's important to consider the column order. Generally, the column that narrows down the data most should come first in the index. It's also worth remembering that composite indexes can become large and use more storage space, especially when including many columns. It's crucial to find a balance between the benefits of improved query performance and the cost of increased storage usage.

A covering index is another useful indexing technique that can help optimize query performance. The concept of a covered index relates to the idea of a query being 'covered' by an index.

A query is considered 'covered' if all the columns referenced in the select, where, and join clauses of the query are included in the same index. In other words, the database engine can retrieve all the necessary information from the index itself without having to perform additional lookups in the underlying table.

Using a covered index can significantly improve the performance of certain queries, as the database can answer the query by using the index alone, reducing disk I/O operations. It's particularly beneficial for large tables and queries that return a small subset of columns but potentially many rows.

Keep in mind that maintaining a covered index, like any index, comes with additional overhead for write operations. If an index includes many columns to cover a wide range of queries, it can become large and consume more storage space. It's important to find a balance between covering more queries and managing storage and performance trade-offs.

A unique index is an indexing tool that, as the name suggests, ensures the uniqueness of the index key values in the database. This index type is valuable for enforcing data integrity and preventing duplicate entries. For instance, columns such as "email" or "user_id" would ideally have unique indexes, as duplicate entries in these fields could lead to data integrity issues.

A unique index operates by prohibiting the entry of two rows with the same index value. This means that if we attempt to insert a record that would result in the same index value as an existing record, the database will prevent us from doing so.

A filtered index, also known as a partial index or a conditional index in some database systems, is a more specialized type of index. It applies a filter on a subset of data, allowing the creation of an index on a specific range or set of values. This can greatly enhance performance and save storage space when dealing with large tables where only a small portion of data is accessed frequently. For instance, a database containing a wide range of product information could use a filtered index to speed up queries specifically related to "in-stock" products. By reducing the size of the index and cutting down on maintenance overhead, filtered indexes provide a focused and efficient way to query data. However, they require a good understanding of the data and query workload to be used effectively.

The availability of filtered indexes is not universal across all relational databases, but is supported by some. Microsoft SQL Server and PostgreSQL are examples of databases that support filtered indexes. On the other hand, MySQL does not support filtered indexes.

Next, let’s discuss some specialized index types that are tailored for very specific situations. They are not universally available but come in handy when a specific situation calls for it. Unlike the indexes mentioned above, many of these specialized indexes are not backed by the B+ Tree.

A bitmap index is a specialized type of database index that uses bitmaps. It is particularly useful when dealing with columns that have a limited number of distinct values, also known as low-cardinality values. Examples might include columns for "marital status," or "yes/no" indicators.

In a bitmap index, each unique value of the column gets its own bitmap, where the number of bits corresponds to the number of rows. The bits are set to 1 if the row has that value, and 0 if it does not. For example, in a "yes/no" column, the "yes" bitmap might have the first bit set to 1 (indicating that the first row corresponds to “yes”), and the "no" bitmap might have the first bit set to 0 (indicating that the first row does not correspond to “no”).

This bitmap representation is very efficient in terms of storage when the cardinality of a column is low. Bitmap indexes can handle complex queries involving multiple predicates efficiently using bitwise operations. These operations include AND, OR, and NOT, which can quickly combine different bitmaps to filter data based on multiple conditions.

However, while bitmap indexes are fast for read operations, they can be slow for write operations because an update to a value requires changing bits in the bitmap. This modification can potentially affect many bits, leading to expensive write costs. Bitmap indexes are best suited for static or read-heavy data that doesn't change frequently.

Oracle Database, IBM Db2, and Microsoft SQL Server are among the database systems that support bitmap indexes. Not all databases support them, for example, MySQL and PostgreSQL do not support bitmap indexes.

A spatial index is a specialized type of index used for indexing multi-dimensional objects, such as geographical coordinates, polygons, or even three-dimensional objects. These indexes are designed to speed up spatial queries, like nearest neighbor searches or range searches. They would be computationally expensive without an index due to the nature of spatial data.

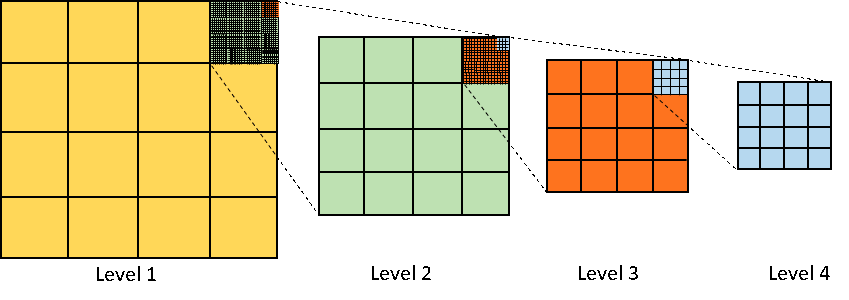

Traditional indexing methods like B-Trees often fall short when dealing with spatial data, as they are primarily designed to handle one-dimensional data. Spatial indexes, such as R-trees or Quad-trees, are optimized to efficiently store and search multi-dimensional data.

Let's consider how an R-tree, one of the most commonly used spatial indexes, works under the hood. In an R-tree, every node represents a bounding box that contains all the objects (or other bounding boxes) in its child nodes. The bounding boxes of sibling nodes may overlap. When a spatial query is performed, the R-tree can exclude many potential results by determining that their bounding boxes do not intersect with the searched area. This makes queries much more efficient than scanning every row in the table.

For instance, an R-tree index would be an excellent choice for a database that powers a mapping application, where common operations might include finding all locations within a given radius of a point or finding the closest point of interest to a specific location.

Spatial indexes are supported by a number of widely used databases. MySQL, PostgreSQL (with the PostGIS extension), Oracle Database, and Microsoft SQL Server all support spatial indexing.

A full-text index is designed to efficiently handle searches in a text column, where the search string can be found anywhere within the column's value. In these cases, standard indexes are often ineffective, as they are optimized for exact matches or range queries rather than partial matches in text data. This is especially useful for dealing with large volumes of text, like articles, books, or other free-form text that contains numerous words.

Unlike traditional indexes, which index the complete value of a column, full-text indexes work by breaking the text in the column into individual words or tokens, and then building an index over these tokens. Each word is stored in the index with a link to its position in the text document.

One common technique used by full-text indexes is the inverted index. An inverted index is a data structure storing a mapping from content, such as words or numbers, to its locations in a document or a set of documents. It is called an "inverted" index because it inverts a page-centric schema (page->words) into a keyword-centric schema (word->pages).

This technique is particularly effective for supporting complex search queries that involve multiple words, phrases, or different forms of a word. The index allows the database to find the documents that contain each word in the query, and then intersect those sets of documents to find the ones that contain all the words.

Full-text indexes are supported by several relational databases such as MySQL, PostgreSQL, Oracle Database, and Microsoft SQL Server. The specific syntax and capabilities can vary between systems. For example, MySQL supports full-text indexing in MyISAM and InnoDB storage engines, and it includes features like stopword filtering and boolean text searches.

Beyond relational databases, full-text indexing is a core feature of specialized search and analytics engines such as Elasticsearch. Elasticsearch is built on Apache Lucene, a software library that provides powerful full-text search capabilities, and extends these capabilities with distributed system features for scaling and managing real-time applications.

It's important to remember that while full-text indexes can greatly enhance text search performance, they can also consume considerable storage space and add overhead to insert and update operations.

A hash index is a type of database index that uses a hash function to map keys to specific locations in an index, making data retrieval extremely efficient. This type of index is particularly well-suited for equality comparisons, such as "=", where the search key is exactly equal to the indexed key.

The principle behind hash indexing is straightforward. The hash function generates a unique hash value, or hash, for each unique key value. These hash values are then used as pointers to the data records. This process makes retrieval operations very fast as the database can directly compute the hash of a search key and immediately locate the corresponding record, without needing to perform a sequential scan or follow B-tree paths.

One limitation of hash indexes is that they are not well-suited for range-based queries. This is because hash indexes do not store keys in sorted order, so operations that rely on a key's position, like "<" or ">", are not efficient.

Hash indexes are available in many database systems, but their use and implementation can vary. PostgreSQL supports hash indexes and uses them as a more efficient alternative to B-tree indexes when only equality comparisons are needed. On the other hand, MySQL uses hash indexes in memory for handling JOIN operations but does not support them as a user-created index type.

While we’ve delved into several specialized index types in this discussion, it’s important to recognize that this list is far from comprehensive. The world of database indexing is vast and constantly changing, with many advanced and niche index types tailored to specific use-cases.

One example is the indexes used in vector databases. This is a growing area that’s sparking considerable interest in the hot field of AI. These indexes are at the cutting edge with active research and ongoing development.

This wraps up our exploration into the basics of database indexing, focusing specifically on those found in relational databases. The journey doesn't end here. In the next issue, we’ll discuss how indexing is used in non-relational databases. We'll round off our discussion on database indexing strategies with practical use cases and best practices, Stay tuned.