In the last issue, we explored various API architectural styles, each with its unique strengths. Despite the many options, REST remains the most popular. However, its popularity doesn’t imply simplicity. REST merely defines resources and the use of HTTP methods. To master the art of crafting REST APIs, we need to follow certain guidelines to ensure that we design efficient, user-friendly APIs.

In this issue, we cover the finer details of REST API design. This includes:

Sniffing out API issues. We learn to identify the telltale signs of inefficient APIs. The “bad smells” hint at a need for a redesign or improvement.

Understanding API maturity. We dive into the Richardson Maturity Model (RMM), a model that helps us distinguish good from bad API design by assessing how closely an API aligns with the REST framework.

Back to basics. To ensure we are all on the same page, we revisit the core components of REST APIs - HTTP verbs and status codes.

To bring these concepts to life, we’ll embark on the first of the three practical examples in this issue with the design of a sign-up and sign-in component. In our next issue, we’ll continue and explore how to construct a shopping cart API and study the Stripe payment API redesign.

How can we tell when an API isn’t living up to its potential and needs a redesign? Much like code, APIs can give off a distinct “smell” when they are not performing as they should. Recognizing these red flags is crucial. Let’s look at some concrete scenarios that suggest an API might not be up to par.

For example, suppose we have thoroughly studied the API documentation, but we are still struggling to understand the nuances of its functionality. This needs for constant clarification from API owners is a clear indication of an API that could be more user-friendly.

Consider another example where API parameters and results are vaguely defined. This lack of clarity can lead to confusion and potential errors. It slows down development and hinders effective collaboration between teams.

Also, think about a situation where our front-end and back-end teams find themselves needing to collaborate extensively just to test and validate API behaviors. This level of coordination overhead suggests an API that isn’t as intuitive or well-documented as it should be.

As API owners, we may notice different sets of red flags. If we find ourselves constantly fielding API usage queries, it is like we are wearing a part-time customer service hat. This scenario points to an API that might benefit from more detailed documentation and possibly a more intuitive design.

Another telltale sign can be an influx of requests for minor enhancements. If it feels like we are always tweaking and adjusting our APIs, it might suggest that they are not as robust or flexible as they need to be.

These real-world examples highlight the kind of challenges that indicate our APIs could use some fine-tuning.

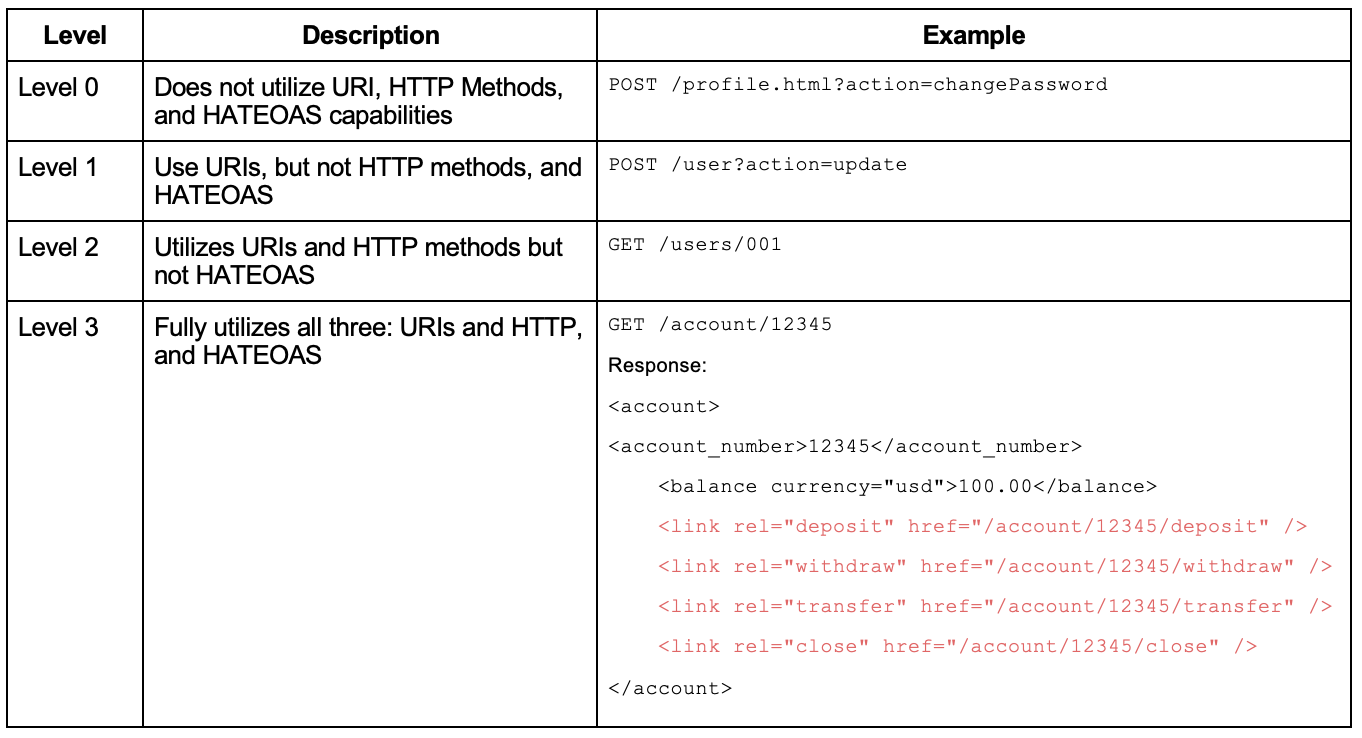

The Richardson Maturity Model (RMM) [3], introduced by Leonard Richardson in 2008, serves as a valuable tool to better understand the concept of API maturity and how well an API conforms to the REST concepts. This model helps us identify the strengths and weaknesses of our API design.

The RMM defines four levels to assess how closely an API conforms to the REST framework. The main factors that decide the maturity of a service are its URI, HTTP methods, and HATEOAS (Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State).

At Level 0, APIs use a single URI and a single HTTP method, typically POST. This approach does not leverage the true capabilities of the HTTP protocol and lacks a uniform way to interact with system resources. Martin Fowler famously called this level “The Swamp of POX (Plain Old XML)” due to its simplistic, RPC-style system.

Level 1 introduces the concept of resources, a cornerstone of RESTful design. Each resource is uniquely identified by a URI, creating an easier way to manage and interact with different elements of a system. However, it still uses only one HTTP method, POST, limiting the full potential of REST.

Level 2 represents an advancement in RESTful design. The services at this level not only use unique URIs for resources but also take advantage of different HTTP methods (like GET, POST, PUT, DELETE) that correspond to operations on these resources. This approach makes our APIs more intuitive and aligns them more closely with the principles of the web. This maturity level is the most popular.

Level 3 brings in the concept of HATEOAS (Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State). HATEOAS makes our APIs self-descriptive, improving their usability and discoverability. When a client interacts with a resource, the API provides information not just about the resource itself, but also about related resources and possible actions, all represented through hypermedia links.

In the example above, when we request to query account 12345, not only do we receive the account balance ($100), but the response also guides us on the next steps and how to execute them via URIs. For instance, we could deposit more money into account 12345 by navigating to /account/12345/deposit.

The RMM offers an effective framework to help us better understand and implement RESTful principles in our API design. It is essential to remember, as we strive to improve our APIs, that Level 2 is a prerequisite for REST [3].

When designing a system, we often encounter two layers: the web service layer, which is responsible for handling web requests, and the service layer, where the real work occurs, such as interacting with databases, handling message queues, and communicating with other services.

At the web service layer, we leverage HTTP verbs. These verbs define the operations we can perform on various resources. At the service layer, we utilize CRUD operations (Create, Read, Update, Delete) to define these operations.

The diagram below lists the common HTTP verbs and their mappings to service methods. It is essential to understand that there isn’t always a direct one-to-one mapping between HTTP verbs and service methods. For example, the GET verb can be used to retrieve a single resource or an entire list of resources. Similarly, both PUT and PATCH verbs can be used to modify a resource. However, the PATCH verb is specifically used when we want to make partial modifications to a resource.

While the five HTTP methods should satisfy most of our needs, there might be scenarios where we need to define custom operations. We have two ways to approach this:

Map custom operations to standard HTTP verbs. For example, we could map a search operation to the GET verb. However, this might lead to some confusion as the verb might not entirely align with the operation’s purpose. It is vital to have comprehensive API documentation to clarify these mappings.

Define a custom HTTP method. In some cases, we might need a specific operation not covered by standard HTTP verbs. For example, in online games, we might need to reset a match. We can define a custom method, such as RESET, for this purpose.

REST is built on the HTTP protocol. Therefore, our APIs should use HTTP status codes to ensure consistent and predictable behavior. The diagram below shows some common HTTP status codes.

However, HTTP status codes are not exhaustive for all the possible outcomes of an API call. We should also establish our own set of internal status codes or error codes to communicate specific service-related issues. One efficient way of managing these codes is by maintaining a common library for all the codes in the system. It facilities easy registration and sharing across different code repositories.

For example, let’s assume the user service uses message codes in the range of 50000 to 59999, while the shopping cart service uses codes from 60000 to 69999. We can wrap these message details in an HTTP response and send them back to the clients. This practice greatly benefits customer service, as they can easily identify issues based on the returned code.

A golden rule we should always follow is to return a code for every response, even if it is a timeout. Adhering to this rule ensures predictable and consistent behavior. It is crucial for maintaining a high-quality service.

Let’s explore a common feature of most websites - the registration and login component. We’ll divide this into three steps:

Basic design

It is important that our APIs meet functional requirements and the URLs are intuitive enough to express their purpose.

Effective APIs

Taking a step further, we need to evaluate the relationships among resources, API performance, and backward and forward compatibility of APIs.

Secure APIs

This addresses the security aspect of APIs. We need to ask: Is the API vulnerable to DDoS (Distributed Denial-of-Service) attacks? Does it require login status?

We use Stripe’s sign-up and sign-in component as an example. The diagram below provides screenshots.

For signing up, we need to create a new account using the user’s email, name, country, and password. The outcomes might be:

The account is created successfully

The email is already registered

If the account is successfully created, a verification email is sent to the user’s email. They must click the link in this email to complete the registration.

In this process, our resource is the user. We should design a system to generate user IDs. While we won’t dive deep into the design of the ID generator, we should remember that the user ID will appear in the URL. Therefore, we need to consider API safety. We’ll discuss more in the “Secure APIs” section.

Here are the REST APIs we’ll use:

Note that Stripe uses this URL for registration:

POST https://dashboard.stripe.com/register?email={email}

This is typical for many websites, where the URL is designed according to the frontend design. Since this is a registration page, the URL is named register. This is more intuitive than REST-style API because the verb is included in the URL.

We also didn't design a REST-style API for the email verification API (see below example), since the link must be clicked in an email where GET is the easiest to implement:

POST /verification/{token}

In a nutshell, there is no one-size-fits-all solution in API designs. In cases where system designs change frequently, RESTful APIs may not be easy to implement.

Once we have registered on the website, we can log in using the email and password. We list the API in the table below:

To verify that we are humans, we need to complete a reCaptcha prompt. This falls outside the scope of API design but should be included in the system or product design.

In this section, we'll enhance the API designs from Step 1. Maintaining APIs is as vital as maintaining the codebase.

API Versioning

As business requirements evolve, we may need to redesign APIs. It is not ideal to require all API consumers to upgrade at the same time. There are two practical ways to maintain backward compatibility: adding a version number to the URL, or adding a version number to the HTTP header. Take the sign-up page as an example:

POST /v1/users

Accept-version: v1

Idempotency

POST requests are not idempotent. If we call the same POST request N times, N new resources will be created. Normally, the browsers don’t cache POST requests, and we can’t bookmark POST URLs. In the sign-up example mentioned above, this might not be a significant issue because we can perform backend checks to ensure we’re not creating user accounts for the same email address.

However, if we are designing a trading app and POST an order many times, this will create numerous new orders in the system. A feasible solution is to carry a request ID in the HTTP header, allowing the service to reject duplicate request IDs. A request ID can be generated based on the order type, quantity, price, etc., and anything that can be used to compose a unique identifier.

“Remember me” feature

Once the user logs in, they can stay signed in for a period. This feature enhances user experience. After the initial login, the server issues a token. This token is stored on the client and used every time the client sends a request to the server. After a period of time, the token expires, and the user needs to enter their credentials again to log in.

System security is not solely the Ops team’s responsibility. Poorly designed APIs often invite unnecessary problems. Let’s go over some examples.

User ID

User IDs are internal system information and should be carefully designed. The use of sequential numbers for user IDs might seem appealing but could expose system information to attackers. In addition, competitors might deduce user growth information from sequential IDs, which isn’t ideal in a business environment where company secrets are highly valued.

In general, user IDs should be unpredictable. For example, Stripe uses strings like “acct_xxxRbrL6xxxxDQxx” as account IDs.

Password storage

In the sign-up example, we use plaintext passwords. Passwords stored directly in a database are at risk of theft. Typically, we generate a salt with a password and store the salt and hash result in the database. A salt is a unique, randomly generated string added to each password during the hashing process. During the sign-in process, the entered password is hashed together with the salt. The hash result is then compared to the persisted hash result.

We should also consider passwordless authentications for our system, as we’ve discussed in previous issues.

Anonymous Status vs. Signed-in Status

When we design resources, we should specify which resources need protection. Public resources can be accessed by anonymous users, while protected resources can only be accessed by logged-in users. Failing to do so leaves the system susceptible to security breaches.

For example, user profiles are protected information, but daily platform transaction metrics are public. For protected resources, we redirect the page to the login page if the user does not carry a signed-in status.

In our next issue, we’ll continue and explore how to construct a shopping cart API and study the Stripe payment API redesign.