This is part 2 of the Crash Course in Caching series.

A distributed cache stores frequently accessed data in memory across multiple nodes. The cached data is partitioned across many nodes, with each node only storing a portion of the cached data. The nodes store data as key-value pairs, where each key is deterministically assigned to a specific partition or shard. When a client requests data, the cache system retrieves the data from the appropriate node, reducing the load on the backing storage.

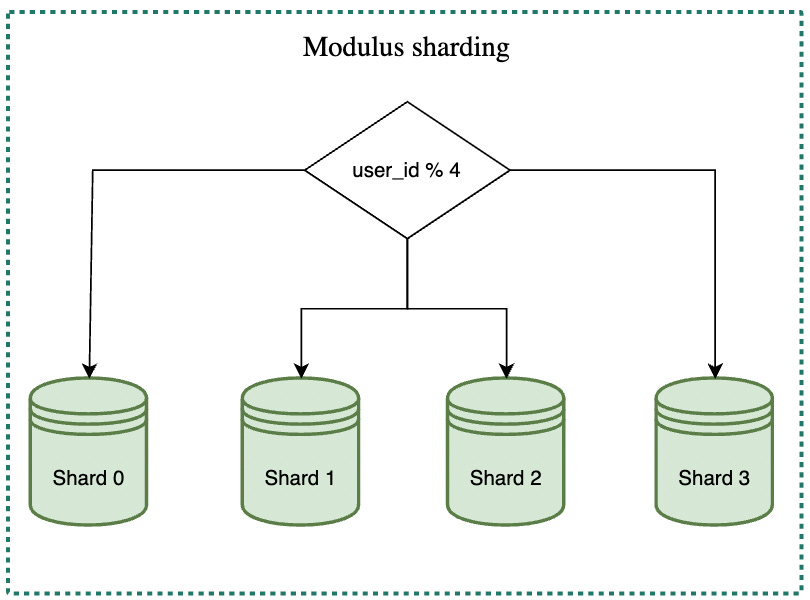

There are different sharding strategies, including modulus, range-based and consistent hashing.

Modulus sharding involves assigning a key to a shard based on the hash value of the key modulo the total number of shards. Although this strategy is simple, it can result in many cache misses when the number of shards is increased or decreased. This is because most of the keys will be redistributed to different shards when the pool is resized.

Range-based sharding assigns keys to specific shards based on predefined key ranges. With this approach, the system can divide the key space into specific ranges and then map each range to a particular shard. Range-based sharding can be useful for certain business scenarios where data is naturally grouped or partitioned in specific ranges, such as geolocation-based data or data related to specific customer segments.

However, this approach can also be challenging to scale because the number of shards is predefined and cannot be easily changed. Changing the number of shards requires redefining the key ranges and remapping the data.

Consistent hashing is a widely-used sharding strategy that provides better load balancing and fault tolerance than other sharding methods. With consistent hashing, the keys and the nodes are both mapped to a fixed-size ring, using a hash function to assign each key and node a position on the ring.

When a key is requested, the system uses the same hash function to map the key to a position on the ring. The system then traverses the ring clockwise from that position until it reaches the first node. That node is responsible for storing the data associated with the key. Adding or removing nodes from the system only requires remapping the keys that were previously stored on the affected nodes, rather than redistributing all the keys, making it easy to change the number of shards with a limited amount of data rehashed. Refer to the reference material to learn more about consistent hashing.

In this section, we will provide an in-depth analysis of various cache strategies, their characteristics, and suitable use cases.

Cache strategies can be classified by the way they handle reading or writing data:

Read Strategies: Cache-Aside and Read-Through

Write Strategies: Write-Around, Write-Through, and Write-Back

Cache-aside, also known as lazy loading, is a popular cache strategy where the application directly communicates with both the cache and storage systems. It follows a specific workflow for reading data:

The application requests a key from the cache.

If the key is found in the cache (cache hit), the data is returned to the application.

If the key is not found in the cache (cache miss), the application proceeds to request the key from storage.

The storage returns the data to the application.

The application writes the key and corresponding data into the cache for future reads.

Cache-aside is versatile, as it can accommodate various use cases and adapts well to read-heavy workloads.

Pros:

The system can tolerate cache failures, as it can still read from the storage.

The data model in the cache can differ from that in the storage, providing flexibility for a variety of use cases.

Cons:

The application must manage both cache and storage, complicating the code.

Ensuring data consistency is challenging due to the lack of atomic operations on cache and storage.

When using cache-aside, it is crucial to consider other potential data consistency issues. For instance, if a piece of data is written to the cache, and the value in the storage is updated afterward, the application can only read the stale value from the cache until it is evicted. One solution to this problem is to set an acceptable Time-To-Live (TTL) for each cached record, ensuring that stale data becomes invalid after a certain period. For more stringent data freshness requirements, the application can combine cache-aside with one of the write strategies that are discussed below.

The read-through strategy is another common caching approach where the cache serves as an intermediary between the application and the storage system, handling all read requests. This strategy simplifies the application's role by delegating data retrieval responsibilities to the cache. Read-through is particularly suitable for read-heavy workloads and is commonly employed in cache libraries and some stand-alone cache providers. The basic workflow for read-through follows these steps:

The application requests to read a key from the cache.

If the key is found in the cache (cache hit), the data is returned to the application.

If the key is not found in the cache (cache miss), the cache requests the key from the storage.

The cache retrieves the data from storage, writes the key and associated data into the cache, and returns the data to the application.

In contrast to cache-aside, where the application is responsible for fetching data from storage and writing it to the cache, the read-through strategy delegates these tasks to the cache itself.

Pros:

The application only needs to read from the cache, simplifying the application code.

Cons:

The system cannot tolerate cache failures, as the cache plays a crucial role in the data retrieval process.

The cache and storage systems must share the same data model, limiting the flexibility in handling different use cases.

Similar to cache-aside, data consistency can pose challenges in a read-through strategy. If the data in the storage is updated after being cached, inconsistencies may arise. To address this issue, we can implement write strategies that ensure data consistency between the cache and storage systems.

Write-around is a straightforward caching strategy for managing data writes, where the application writes data directly to the storage system, bypassing the cache. This approach is often combined with cache-aside or read-through strategies in real-world systems. The basic workflow for write-around is as follows:

The application writes data directly to the storage system.

After the data is written to the storage, one of the following steps may be taken:

Write the key-value pair to the cache. However, this may lead to concurrency conflicts if multiple threads update the same key.

Invalidate the key in the cache. This popular choice ensures that subsequent read requests for the same key will result in a cache miss, and the updated value will be fetched from the storage.

Do nothing with the cache, relying solely on the Time-To-Live (TTL) mechanism to invalidate stale cached data.

Pros:

Write-around is intuitive and simple, effectively decoupling cache and storage systems.

Cons:

If data is written once and then read again, the storage system will be accessed twice, potentially causing performance issues.

When data is frequently updated and read, the storage system is accessed multiple times, rendering cache operations less effective.

Write-through is a caching strategy in which the cache serves as an intermediary for data writes, similar to read-through's role in data reads. In this approach, the cache is responsible for writing data to the storage system and updating the cache accordingly. Write-through is often combined with read-through to provide a consistent caching solution for both read and write operations. DynamoDB Accelerator (DAX) is a good example of such a cache in the market. It sits inline between DynamoDB and the application.

The basic workflow for write-through includes the following steps:

The application writes to the cache endpoint.

The cache writes the data to the storage system and updates the cache if the write operation is successful.

Write-through is particularly well-suited for situations where data is written once and read multiple times, ensuring that all data read from the cache is up-to-date.

Pros:

The application only needs to write data to the cache, simplifying the process and reducing complexity.

As data is first written to the cache, all read operations from the cache retrieve the most recent data, making this strategy ideal for scenarios where data is written once and read many times.

Cons:

Write-through introduces additional write latency, as the operation must be performed on both the cache and storage systems. This may not be optimal if data is written and never read again.

If data is successfully written to the storage but not updated in the cache, the cached data becomes stale. To address this issue, the cache can first invalidate the key, then request to write the data to the storage, and finally update the cache only if the write operation succeeds. This ensures that the cached key will be either updated or invalidated, maintaining data consistency.

Write-Back is a caching strategy similar to write-through, with the primary difference being that write operations to the storage system are asynchronous. This approach offers improved write performance by periodically writing updated records from the cache to the storage system in batches. Write-back is often combined with read-through to provide a comprehensive caching solution. The basic workflow for write-back consists of the following steps:

The application writes data to the cache, and the data is persisted in the cache.

The cache periodically writes updated records to the storage system in batches.

Some cache systems, like Redis, use a write-back strategy for periodic persistence to an append-only file (AOF).

Pros:

Write-back offers lower write latency compared to write-through, resulting in better performance for write operations.

The strategy reduces the overall number of writes to the storage system and provides resilience to storage failures.

Cons:

There may be temporary data inconsistency between the cache and storage systems, which is a trade-off for better availability.

If the cache fails before writing data to the storage, the latest updated records may be lost, which is not acceptable in some scenarios. To mitigate the risk of data loss due to cache failures, cache systems can persist write operations on the cache side. When the cache restarts, it can replay the unfinished operations to recover the cache and write data to the storage system. This approach ensures eventual data consistency between cache and storage systems.

Cache strategies can be combined to create robust and effective caching solutions tailored to specific use cases and requirements. Some of the popular cache strategy combinations include:

Cache-aside & write-around: Commonly used in systems such as Memcached and Redis, this combination takes advantage of cache-aside's read capabilities and write-around's simple and efficient write operations.

Read-through & write-through: This combination leverages the cache as an intermediary for both read and write operations, ensuring data consistency between cache and storage systems. Examples of this combination include DynamoDB Accelerator (DAX).

Read-through & write-back: This combination offers the benefits of read-through for reading data and write-back for efficient write operations. The asynchronous nature of write-back improves write performance while maintaining data consistency with read-through.

There are also less common combinations, such as:

Read-through & write-around: This combination uses read-through for handling read requests and write-around for direct writes to storage, offering a mix of cache delegation and decoupling.

Cache-aside & write-through: In this combination, cache-aside handles read operations while write-through ensures consistent data writes through the cache as an intermediary.

There is no one-size-fits-all caching solution for all scenarios. The choice of cache strategy combinations depends on factors such as traffic patterns, data access requirements, and system design constraints. Evaluating and selecting the most suitable combination for a specific use case is crucial for optimizing system performance and maintaining data consistency.

To be continued.