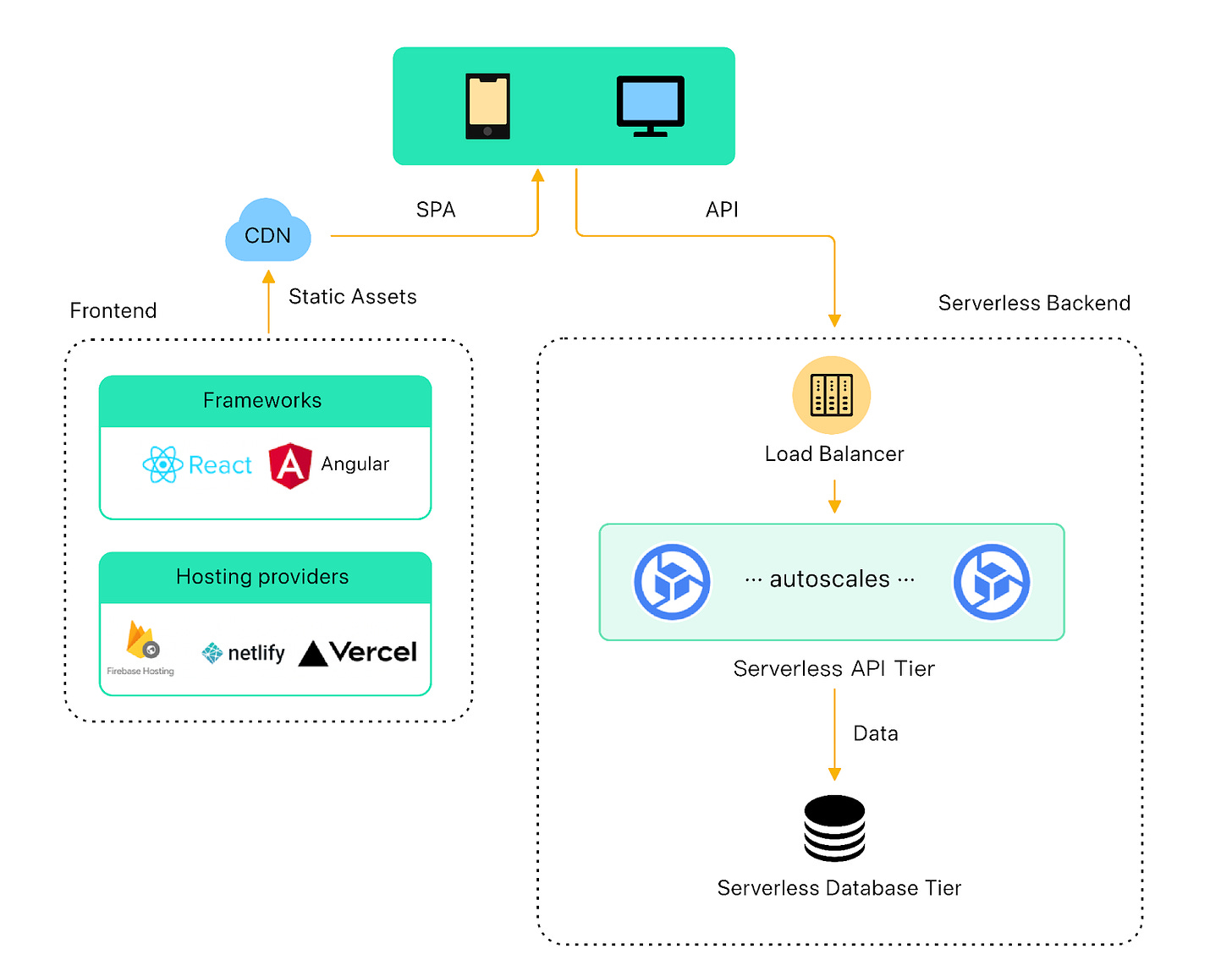

In part 3 of this series, we explored the modern application stack for early-stage startups, including a frontend hosting platform, a serverless API backend, and a serverless relational database tier. This powerful combination has taken us far beyond what we used to be able to do with a single server.

As traffic continues to scale, this modern stack will eventually reach its limits. In this final part of the series, we examine where this modern stack might start to fall apart, and explore strategies to evolve it to handle more traffic.

At a certain threshold, handling the scale and complexity of the application requires an entirely new approach. We discussed microservice architecture briefly earlier in the series. We will build on that with an exploration of how hyper-growth startups can gradually migrate to a microservice architecture by leveraging cloud native strategies.

As traffic continues to scale, the modern application stack will start to run into issues. Depending on the complexity of the application, the stack should be able to handle low hundreds of thousands of daily active users.

Well before we run into performance issues, we should have a robust operational monitoring and observability system in place. Otherwise, how would we know when the application starts to fall apart due to rising traffic load?

There are many observability solutions in the market. Building a robust system ourselves is no simple task. We strongly advise buying a solution. Many cloud providers have in-house offerings like AWS Cloud Operations that might be sufficient. Some SaaS offerings are powerful but expensive.

To get an early warning of any system-wide performance issue, we suggest monitoring these critical performance metrics. Keep in mind the list is not exhaustive.

For database:

Read and write request rate.

Query response time. Track p95 and median at the very least.

Database connections. Most databases have a connection limit. Track the number of connections to identify when to scale the database resources to handle increased traffic.

Lock contention. It measures the amount of time a database spends waiting for locks to be released. It helps identify when to optimize the database schema or queries to reduce contention.

Slow queries. It tracks the number of slow queries. It is an early sign of trouble when the rate starts to increase.

For the application tier, the serverless platform should provide these critical metrics:

Incoming request rate.

Response time. It measures the time it takes for an application to respond to a request. Track at least p95 and median.

Error rate. It tracks the percentage of requests that result in an error.

Network throughput. It measures the amount of network traffic the application is generating.

Now that we are armed with the data, let’s see where an application is likely to fall apart first.

Every application is different, but for most applications, the following sections discuss the areas that are likely to show the first signs of cracks.

The first place that could break is the database tier. As traffic grows, the combined read and write traffic could start to overwhelm the serverless relational database. This limit could be quite high. As we discussed before, with a serverless database, the compute tier and the storage tier scale independently. The compute tier transparently scales vertically to a bigger instance as the load increases.

At some point, the metrics would start to deteriorate and it could start to overload the single serverless database. Fortunately, the playbook to scale the database tier is well-known, and it stays pretty much the same as in the early days.

In part 2 of this series, we discussed three strategies for scaling the database tier in the traditional application stack. These strategies are still applicable to the modern serverless stack.

For a read-heavy application, we should consider migrating the read load to read replicas. With this method, we add a series of read replicas to the primary database to handle reads. We can have different replicas handle different kinds of read queries to spread the load.

The drawback of this approach is replication lag. Replication lag refers to the time difference between when a write operation is performed on the primary database and when it is reflected in the read replica. When replication lag occurs, it can lead to stale or inconsistent data being returned to clients when they query the read replica.

Whether this slight inconsistency is acceptable is determined on a case-by-case basis, and it is a tradeoff for supporting an ever-increasing scale. For the small number of operations that cannot tolerate any lags, those reads can always be directed at the primary database.

Another approach to handle the ever-increasing read load is to add a caching layer to optimize the read operations.

Redis is a popular in-memory cache for this purpose. Redis reduces the read load for a database by caching frequently accessed data in memory. This allows for faster access to the data since it is retrieved from the cache instead of the slower database. With fewer read operations performed on the database, Redis reduces the load on the database cluster and enhances its overall scalability. Managed Redis solutions are available through many cloud providers, reducing the burden of operating a caching tier on a day-to-day basis.

Database sharding is a technique used to partition data across multiple database servers based on the values in one or more columns of a table. For example, a large user table can be divided based on user ID, resulting in multiple smaller tables stored on separate database servers. Each server handles a small subset of the rows that were previously managed by the single primary database, leading to improved query performance as each shard handles a smaller subset of data.

However, database sharding has a significant drawback as it adds complexity to both the application and database layers. Managing and maintaining an increasing number of database shards becomes more complex. Application developers need to implement sharding logic in the code to ensure that the correct database shard is accessed for a given query or transaction. While sharding improves query performance, it can also make it harder to perform cross-shard queries or join data from multiple shards. This limitation can restrict the types of queries that can be performed.

Despite these drawbacks, database sharding is a useful technique for improving the scalability and performance of a large database, particularly when vertical scaling is no longer feasible. It is essential to plan and implement sharding carefully to ensure that its benefits outweigh its added complexity and limitations.

Rather than sharding the database, another feasible solution is to migrate a subset of the data to NoSQL. NoSQL databases offer horizontal scalability and high write rates, but at the expense of schema flexibility in the data model. If there is a subset of data that does not rely on the relational model, migrating that subset to a NoSQL database could be an effective approach to scaling the application.

This approach reduces the read load on the relational database, allowing it to focus on more complex queries while the NoSQL database handles high-write workloads. It is important to carefully consider which subset of data is migrated, and the migration process should be planned and executed carefully to avoid data inconsistencies or loss.

The serverless API tier is designed to be highly scalable, and scaling is typically managed by the provider. This tier can handle tens to hundreds of thousands of daily active users. However, it's important to note that every serverless platform has a limit on the number of simultaneous connections it can handle, and the limit can vary widely between platforms.

For cloud functions, the limit is typically around tens of thousands of daily active users, while managed container platforms can handle hundreds of thousands of users. It's important to keep in mind that these are rough estimates and the limits are highly dependent on the specific workload of the application.

As the application approaches these limits, it is likely that it has become more complex. It's crucial to monitor the application's performance metrics, including the slow query metric at the database tier, to identify and fix any costly and slow code paths.

If the application is highly tuned and still running into platform scaling limits, breaking it into modules is an effective approach. Each module can be served by a separate pool of serverless computing resources. This modular approach is similar to how a monolithic application can be transformed into a modular monolith, as discussed in part 2 of this series. With the API gateway, routing traffic to different serverless resources is straightforward.

Breaking the application into smaller, more manageable pieces makes it easier to scale and maintain. This approach can help mitigate any potential issues with the scaling limitations of the serverless platforms.

For most companies, breaking up the application into a modular monolith is likely sufficient. However, for companies experiencing hyper-growth where traffic continues to increase exponentially, it might start to make sense both technically and organizationally to consider slowly migrating to a microservice architecture.

In part 2, we briefly discussed microservice architecture, which structures an application as a collection of small, interdependent services, with each service running its own processes and communicating with each other through lightweight protocols like gRPC.

We will build on that discussion and explore in more detail how a hyper-growth organization could leverage cloud native strategies to effectively migrate to a microservice architecture.

Cloud native strategies are a set of blueprints for building highly available web-scale applications on the cloud. It is a set of strategies that promise the following:

Agility. Cloud native strategies enable organizations to develop, test and deploy complex applications more quickly and with greater agility.

Scalability. Cloud native strategies enable organizations to scale their applications more easily and with greater flexibility.

Resilience. Cloud native strategies improve the resilience of applications by providing redundancy, automatic failover, and fault tolerance.

There are four core pillars to consider when following cloud native strategies to migrate to a microservice architecture.

The first pillar is the application architecture.

We have already touched on this. Cloud-native applications are made up of multiple small, interdependent services called microservices. By using the cloud-native approach, an organization breaks the functionalities of a large application into smaller microservices. These services are designed to be small and self-contained, allowing teams to take ownership of their own services, and deploy and scale them on their own timeline.

The microservices communicate with each other via well-defined APIs. gRPC is a popular inter-service communication protocol. Some microservices communicate with each other over a message bus that provides decoupling and enables asynchronous processing. Using a message bus adds a level of complexity to the system, but it is a good option when a use case requires asynchronous processing or higher fault tolerance.

The second pillar is container orchestration.

Cloud native applications are packaged in containers. Containers are lightweight components that contain everything needed to run a microservice in any environment.

At the scale where microservice architecture is required, there are a large number of these container instances to manage. Container orchestration is an essential component for managing this complexity. Container orchestration manages a large number of containers so all the microservices can run smoothly as a single unified application. It oversees and controls where containers run. It detects and repairs failures, and it balances the load between microservices.

The third pillar is the development process.

In a microservice architecture, different services are developed, deployed, and scaled independently of each other. This requires a high level of collaboration between development and operations teams, as well as a significant investment in automation for the development and deployment process.

DevOps is a development practice that emphasizes collaboration, communication, and automation between development and operations teams to deliver cloud-native applications quickly and reliably.

A critical component of DevOps is CI/CD. It enables teams to automate the software development and deployment process, making it faster and more reliable.

The Continuous Integration part of CI/CD refers to the practice of regularly merging code changes into a shared repository and running automated tests to ensure that the code is working as expected.

The Continuous Delivery part of CI/CD refers to the practice of automating the deployment of the software to production environments, often through the use of automated deployment pipelines.

The last pillar is the adoption of Cloud Native Open Standards.

As the Cloud Native ecosystem matures, critical components become standardized and best practices become widely available. Being cloud native means leveraging these standardized components as building blocks and following these best practices as they become available.

Some of the well-known projects based on these standards are Kubernetes for container orchestration, Jaeger for distributed tracing, and Istio for service mesh.

By leveraging these battle-tested cloud native components, it frees an organization from having to worry about basic functionalities like logging, tracing, and service discovery. This allows developers to focus on what matters, which is their own microservice applications.

Migrating a large monolithic stack to microservices can bring numerous benefits such as increased agility, scalability, and flexibility. We can not stress enough that this is a complex topic, and it requires careful planning and execution. While there is not a clear playbook that we could follow, here are some practical steps that can help make the transition smoother.

The first step towards a successful migration is to clearly define the order in which we break down the monolithic application into microservices. This means analyzing the application's architecture and identifying the functionalities that can be broken down into smaller, independent services. Consider how to manage data consistency across services to ensure that the application maintains its integrity. This step is made a bit easier if the application is already a modular monolith.

Once the plan is defined, start migrating the smallest and lowest-impact portions of the monolith first. A perfect first candidate would have very little dependency on other parts of the system. This approach allows time and experience to harden the foundation of the microservice stack before moving the core traffic over. This not only reduces the risk of disrupting the overall application but also allows developers to learn and adapt to the new architecture gradually.

As the migration progresses, monitor the performance of the microservices carefully. This helps identify potential issues that can affect the overall performance of the system. Establish a core set of metrics to compare against the metrics from the monolith to make sure that the performance characteristics are within the expected range.

Feature flags are a powerful technique for separating the deployment of the microservice from its activation. This means that a microservice can be deployed but not activated until it's tested and deemed ready to handle the traffic. This approach allows gradual migration of traffic and a quick revert if things were to go wrong, minimizing the risk of any issues affecting the entire system.

Finally, migrating a monolithic application to microservices is not just a technical process. It requires coordination and communication between different teams, including developers, operations, and business stakeholders. Maintaining open communication and collaboration can help identify potential issues and ensure that the migration stays on track.

Migrating a large monolithic stack to microservices can be a complex and challenging process, but by following these best practices, an organization can build a large team to support a microservice application that could scale well into hundreds of millions of daily active users.

In this 4-part series, we explored the process of scaling an application from zero to millions of users. We discussed the conventional method of starting with a single server connected to the Internet, and gradually scaling up to a large-scale microservice architecture serving many millions of users.

We explored the recent trend in the cloud and serverless computing, and illustrated how these modern technologies allowed us to start with an application that was much more powerful than the single server approach.

As we progressed through each phase of growth, we encountered numerous improvements and tradeoffs that needed to be considered. It became clear that making sound tradeoff decisions is a crucial skill in software engineering, and that every decision we made had an impact on the overall scalability, complexity, and performance of the application.

Every application has its distinct set of complexities and hurdles. We hope that this series can serve as a valuable guide for you to navigate these challenges while scaling up your application.